Exeter Collaboration for Academic Primary Care (APEx) Blog

Exeter Collaboration for Academic Primary Care (APEx) Blog

Posted by ma403

3 June 2025

An academic primary care workforce often has common research or clinical interests. However, the membership of academic departments is diverse in many ways. By nurturing inclusivity in our academic primary care departments, we can ensure that people’s differences are seen as a benefit, and that their perspectives are shared. To do this, we need to treat all colleagues equally, and ensure that they have fair access to opportunities, resources and support.

We ran a 45-minute workshop at the southwest conference for the Society of Academic Primary Care and invited all of those at the conference to complete an online survey to inform our discussions during the workshop. Attendees were invited to:

when seeking to ensure equality, diversity and inclusivity (EDI) in the academic primary care workforce

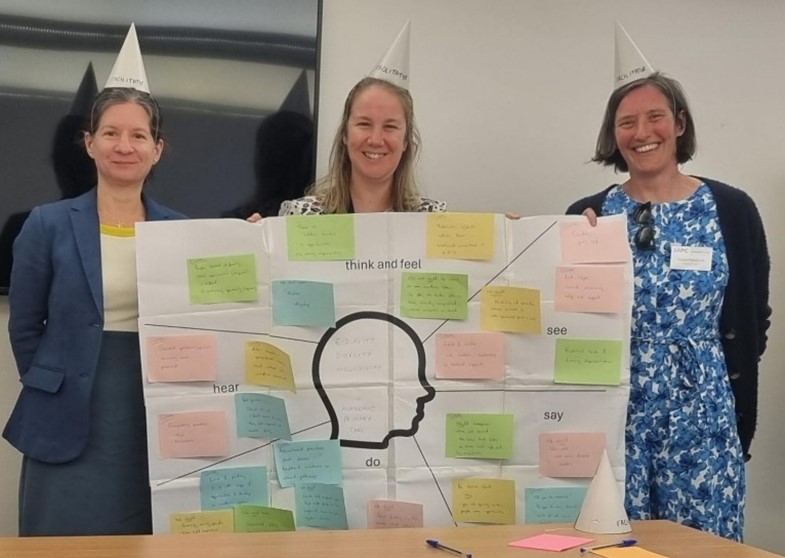

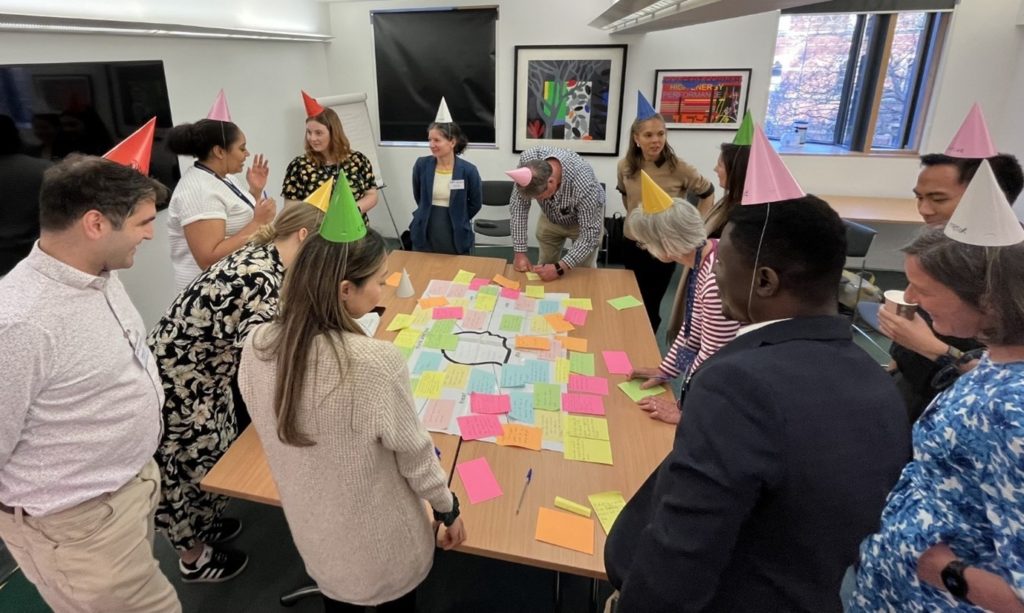

We used a ‘thinking head’, annotated by attendees in real time, allowing people to add hypothetical information about what a member of an academic primary care team may ‘see’, ‘hear’, ‘say’, or ‘think’ in respect of issues relating to EDI, without the need to volunteer specific information about themselves, their departments or their colleagues.

When considering solutions, we used ‘thinking hats’ to encourage attendees to provide a broad, collective perspective, by tailoring their individual perspectives to the label on their hat. Labels encouraged ‘positivity’ and ‘pessimism’ as well as ‘logical’, ‘creative’ and ‘emotional’ responses. Attendees were given the opportunity to swap and try on different hats.

We received 22 responses to the survey, ahead of the workshop, and 14 people attended the workshop itself. Both responders and attendees were themselves representative of a diverse group of individuals by sociodemographic characteristics and career stage. However, it would not be appropriate to report detail here.

Challenges

The workshop attendees acknowledged a tension between meritocracy and tokenism when seeking to ensure EDI, with individuals at risk of feeling exploited if they perceived that they had only been included because of a minority characteristic, for example. It was felt that, too often, the burden of addressing EDI falls on those already marginalised, without recognition or reward for their efforts.

A lack of visible equality and inclusivity amongst existing research teams, and therefore a lack of diverse role models, was recognised as a barrier for individuals to be able to visualise their own pathway to career progression or promotion.

Recruitment practices were discussed, with both survey respondents and attendees acknowledging that current practices advantage those who have had the opportunity to follow traditional academic or clinical pathways. This problem can be exacerbated by a lack of funding available for those from underrepresented backgrounds to develop an academic career. Other ‘hidden’ barriers to equal opportunities were discussed, for those who have caring responsibilities.

Solutions

It was suggested that education around the potential for prejudice, including information about who is commonly affected by discriminatory practices, or currently underrepresented in the academic primary care workforce, could help curb unconscious bias. When providing equality of opportunity, it should be made clear as to why underrepresented individuals are being given that opportunity. It was discussed that work to address EDI should be valued as ‘core’ academic work, and audited as such, and that individuals should be asked to demonstrate this work as a component of their criteria for promotion.

Recommendations were made about highlighting success stories (either internal examples or from other institutions) to learn from them and to apply similar practices. A more structured approach to mentorship for underrepresented groups was called for, to include support for psychological wellbeing. Mentorship and sponsorship schemes, tailored to those who are under-represented, was considered vital, with regular (formal and informal) check-ins to ensure people feel valued and not marginalised.

It was suggested that recruitment panels should be provided with better, structured EDI training. Recommendations included a change to recruiting practices so that life experience can be weighted fairly, alongside research or clinical experience. Equitable funding for international PhD students, or opportunities to seek additional funding, were called for. Transparent, upfront communication of employment rights, e.g. maternity leave, was asked for (including for PhD students and those with fellowship awards).

In summary

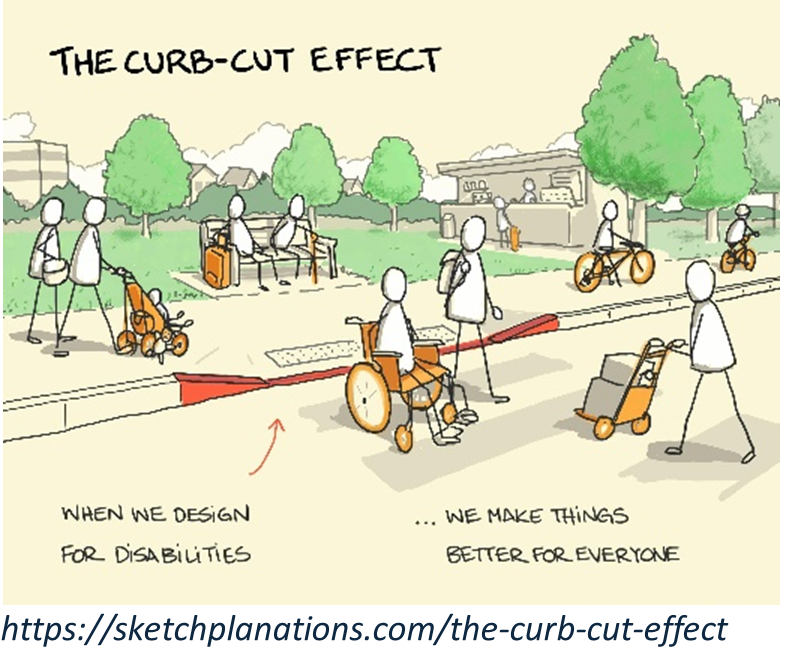

Those who responded to the survey or attended the workshops felt that the projection of positive and inclusive practices, into every aspect of the academic primary care workforce, was vital. They discussed the importance of safe, supportive spaces that allow those facing systemic barriers to thrive, feel they can belong and be themselves, without fearing judgement or prejudice. The concept of ‘lowering the curb’, where addressing the needs of a minority can lead to benefit in a variety of ways for the majority, was received well by all attending the workshop. This echoed the messages conveyed by conference keynote speaker, Lucy Potter @drlucypotter.bsky.social, who outlined her work on Inclusion Health: https://www.bristol.ac.uk/people/person/Lucy-Potter-4b3c4443-6469-4bc0-80c8-424e10046db6/.

Ensuring EDI in the workplace is likely to increase the creativity and productivity of individuals and their teams and therefore the wider academic community. EDI within academic primary care is likely to lead to better problem-solving and decision-making around primary care research priorities.