Exeter Collaboration for Academic Primary Care (APEx) Blog

Exeter Collaboration for Academic Primary Care (APEx) Blog

Posted by ma403

22 July 2025By Dr Samantha van Beurden and Professor Vicki Goodwin

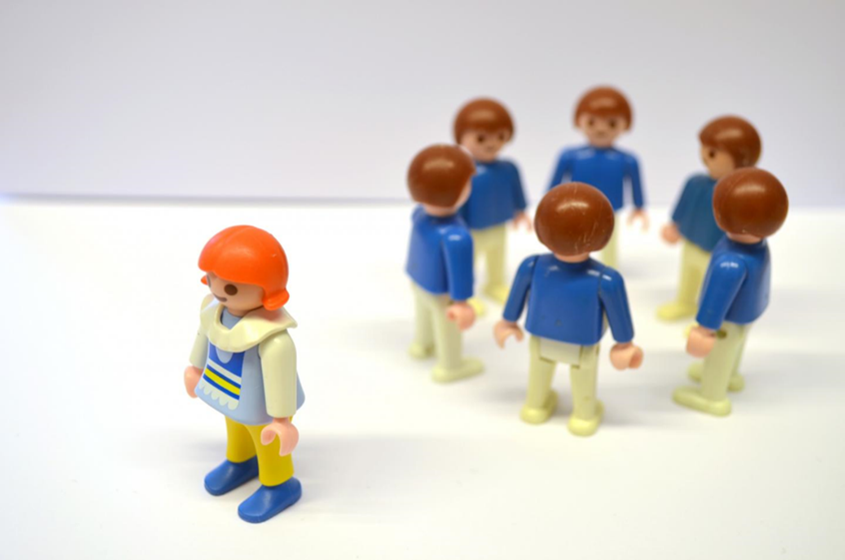

Too often, the people who stand to benefit most from health and care research are the least likely to be included in it. Whether due to age, comorbidities, cognitive differences, language barriers, or cultural mismatches, many groups remain underrepresented in the evidence base that informs care. This exclusion isn’t just a gap in data. It’s a gap in equity, relevance, and impact.

In rehabilitation research, where person-centred care is at the heart of what we do, failing to consider the full diversity of the people with health and care needs means we risk designing research that explicitly or implicitly excludes them or developing interventions that don’t fit real lives. If we want to develop programmes and services that are accessible, acceptable, and truly effective, we need to embed inclusion from the start, not as a tick-box exercise, but as a foundation for good research.

We use the term inclusive research to mean “the intentional engagement of diverse voices, communities, perspectives, and experiences throughout the research process” (Morrow, Vandrevela, & Ross, 2025). This principle challenges us to rethink who is involved in generating knowledge, how decisions are made, and what kinds of insights are valued.

This blog draws on our experiences working to make rehabilitation research more inclusive. From championing the involvement of older people, to co-designing rehabilitation programmes with people from diverse communities, to creatively adapting research methods to welcome broader participation.

Older People Have Stories to Tell. So Why Are They Still Left Out?

By Professor Vicki Goodwin

I’ve been a physiotherapist for 30 years, and from the very beginning, I knew I wanted to work with older people. Not just because of their health needs, but because of their stories. The wisdom, humour, and lived experience older adults bring to every conversation is extraordinary. Yet time and time again, I’ve seen them excluded from the very research designed to inform their care.

As I moved into academia, the frustration deepened. Older people are the greatest users of health and social care services, yet many trials still exclude them, sometimes purely because of age, comorbidities, or cognitive impairment. To me, that’s not just short-sighted. It’s unethical. How can we generate evidence that’s relevant if we deliberately leave out the people we care for?

We are currently leading a project to improve public involvement in dementia research, working closely with people with lived experience of the condition. Using relational and creative approaches that foster co-learning and meaningful engagement are key takeaways. I’ve learned so much from them about how to be a better researcher and a better person.

I’ve also been leading a multidisciplinary effort to change the conversation. Working with colleagues and members of the public, we co-developed recommendations to support the inclusion of older people in health and care research. Ultimately, inclusive research isn’t a luxury or a specialist interest. It’s a responsibility. And it’s the only way to ensure rehabilitation is evidence-based, equitable, and fit for the real world.

“Inclusion in Action: Adapting Digital Cardiac Rehabilitation for South Asian Communities”

By Dr Samantha van Beurden

If rehabilitation is to work for everyone, research needs to reflect the diversity of the people who might benefit from it. Yet in cardiac rehabilitation, we see persistent inequalities, especially among people from ethnic minority backgrounds. South Asian communities, for instance, experience some of the highest rates of hospitalisation and mortality from heart failure yet remain significantly underrepresented in cardiac rehabilitation programmes and research.

That’s what we’re trying to change it through a LEAP-funded study focused on improving the usability, accessibility, and cultural inclusivity of a digital cardiac rehabilitation programme. Building on the success of the home-based REACH-HF intervention, we’re adapting the recently developed digital version (D:REACH-HF) to better meet the needs of older adults from British South Asian communities and their families.

Inclusion is more than translating text or diversifying representation in visuals. We’re reimagining how research is done, from recruitment and design through to data collection and delivery.

We’re working in partnership with community advocates, including South Asian Health Action, to ensure the study feels relevant, respectful, and welcoming. That means meeting people where they are, in community spaces, places of worship, WhatsApp groups, and local networks, and using a variety of communication methods beyond standard participant information sheets. These approaches were suggested by the communities themselves, and they reflect a shift in mindset. We’re not asking people to fit into research, we’re adapting research to fit into people’s lives.

We’re also redesigning our data collection methods to make participation more feasible and inclusive. For example, we’re using “think-aloud” interviews conducted via secure video calls, with interpreters if needed. During these sessions, participants (and sometimes their caregivers) navigate the digital platform and share their thoughts in real time. This method allows us to respond quickly to feedback, make iterative changes, and focus on what really matters to users: usability, relevance, and cultural resonance.

Inclusion, for us, means embedding lived experience, cultural insight, and flexibility into every stage of the process. It’s not an add-on. It’s how we improve the intervention and make sure it works for the people who need it most.

Bringing Inclusion to Life in Rehabilitation Research

What unites our work is a commitment to making research more inclusive, not in name only, but in practice. That means asking difficult questions, not just about who we include, but how, when, and why. It means working with, not just for, the communities we aim to serve. And it means being willing to rethink our methods, our assumptions, and our systems of power.

The intentional engagement of diverse voices, communities, perspectives, and experiences for truly inclusive research takes time, resources, and humility. But it leads to better evidence, better interventions, and ultimately, better care.

Whether we’re designing rehabilitation programmes for older adults, co-creating digital tools with South Asian communities, or rethinking who gets to shape the research agenda, the principle is the same. If we’re not including the people most affected, we’re missing the point.