The grounds and gardens of the University of Exeter’s Streatham Campus have been awarded the title of Accredited Botanic Garden by Botanic Gardens Conservation International (BGCI). The accreditation, which honours that Streatham Campus “conforms to the highest international standards”, distinguishes between botanic and non-botanic gardens in recognising “achievements in plant conservation” [1]. The accreditation was issued in July 2025. In the coming years, the University of Exeter’s Grounds team will develop their role as a botanic garden, namely:

- Focusing on a revised plant collection policy

- Honing custodial responsibilities for the botanic specimens present on campus

- Partaking in collaboration and research opportunities, both within the University and with external partners

- Continuing to digitise plant records and maps

Anthony Cockell, Curator of Horticulture at the University of Exeter, has been leading the application process:

“This accreditation perfectly aligns the aims of the BGCI mission and the University of Exeter Strategy 2030 by combining public gardens, research and educational outreach as part of the international botanic garden sector.”

David Evans, Head of Grounds, is proud of what the team has achieved:

“I am immensely proud of the University Grounds team for achieving accreditation from the BGCI, as it is a reflection of our dedication, expertise and passion for creating and maintaining landscapes that go far beyond simply being beautiful spaces. This recognition places the University among a global network of institutions committed to plant conservation, biodiversity and sustainability, showcasing the team’s professionalism and hard work on an international stage. For the wider University community, this achievement brings a sense of pride and belonging, enhancing the student and staff experience by highlighting the unique value of our grounds as living classrooms, places of wellbeing and biodiversity-rich environments. It reinforces the University’s commitment to sustainability and strengthens our reputation as a forward-thinking institution that cares for both people and the planet.”

What is a Botanic Garden?

A Brief History

Botanic gardens are defined by their focus on growing, documenting, researching and conserving plant collections. Alongside this, they hold outreach responsibilities – gardens should display their plant collections, communicate about their current projects and educate the wider public about plants. These responsibilities differentiate botanic gardens from other green spaces, such as parks or historic gardens. Botanic gardens are, in essence, scientifically led horticultural institutions with a focus on plant conservation and education. Here at Exeter, our newly acquired accreditation places us within this network and we aim to be active in all the aforementioned areas.

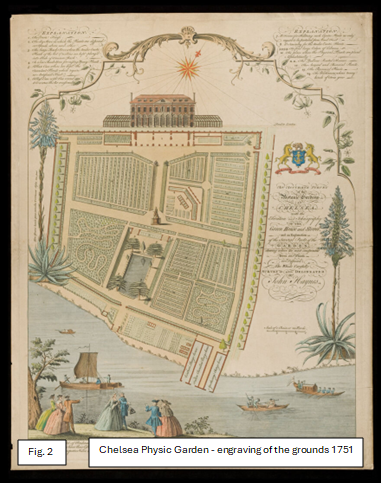

Looking at the history of botanic gardens helps to illustrate where the University of Exeter’s grounds sit in the wider picture, as well as explain why our model is rather unorthodox. The ‘original’ botanic gardens were in the sixteenth century, notably through the ‘Physic Gardens’ of Italy; these University gardens were created for the research of plants with medicinal properties. The Orto Botanico di Pisa – created by Luca Ghini in 1543 at the University of Pisa – was the first of its kind and was followed by other gardens, such as at Padova (1545) and Bologna (1547). Over the following decades, the idea spread across Europe to other Universities, such as Cologne, Leiden and Prague. Oxford Botanic Garden (1621) and Chelsea Physic Garden (1673) were the first of their kind in Britain.

Although their origins lay in botanical research, the following centuries changed the focus for botanic gardens. Powerful European countries of the day, such as England, France and Spain, were undertaking increasingly ambitious expeditions to new, ‘exotic’ regions of the world. Botanic gardens became places to which new plant specimens from these expeditions could be brought for cultivation and research. Some of the United Kingdom’s most famous gardens were formed in this period, such as the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh (1670) and Kew Gardens (1759). The same was the case elsewhere in Europe, with the creation of historic gardens such as Jardin des Plantes in Paris (1626), the Linnaeus Garden of Sweden (1655) and the Real Jardin Botánico de Madrid (1755). These gardens’ purposes became entangled in matters of trade and exploration and many have their roots in Colonialism – a topic discussed by Professor Alexandre Antonelli (Kew’s Director of Science) in ‘It’s time to re-examine the history of botanical collections.’ [4].

By the nineteenth century, botanic gardens were increasingly valued for their beauty. Many municipal gardens were created throughout Europe and the British Commonwealth during this time. There was also growing awareness of the importance of green spaces for health and wellbeing in the face of industrialisation and urbanisation. Meanwhile, new botanic gardens were being established including the first American botanic garden in Missouri (1859).

Following the two World Wars, botanic gardens changed form again. In the United Kingdom, large estates dwindled and many were divided and sold off to organisations such as the National Trust. As a result, more gardens became accessible to the public. In more recent times, botanic gardens have turned their focus back to scientific research and conservation – issues becoming more pressing considering the current biodiversity and climate crises. It is within this milieu that we are growing into our role as a botanic garden here at Exeter – one that blends horticultural interest and research with a native landscape and ecological conservation.

Botanic Gardens Today

Botanic gardens vary widely in form and structure, from large gardens to small private collections. The BGCI’s ‘GardenSearch’ function currently lists 75 accredited botanic gardens globally [5]. All these gardens share the common goals of conservation and education but differ in terms of organisation, structure, access, size and plant collection types, as well as their specific vision and mission statements.

A core feature of botanic gardens is which plants are grown and how the gardens organise their collections. Royal Botanic Garden Sydney, for example, organises their collections based on habitats and hosts twelve sections, such as tropical and subtropical coniferous forests and specialist island habitats. Other gardens focus on the geographical origin of plants. The National Botanic Garden Wales’ Great Glasshouse is divided into six regions including Chile and the Canary Islands. Their team also work towards conserving native Welsh flora via propagation and local seed collection and conservation, with a focus on threatened plant species like Rumex rupestris (shore dock) a highly threatened plant with a valuable stronghold along the Welsh coast [8].

Botanic garden size and access ranges from paid-for private to free universal entry. The United Kingdom’s largest botanic garden is the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew with a collection of over 50,000 plants. The world-famous gardens attract visitors from across the globe and are funded from public, charitable and commercial income. Some botanic gardens are private, such as the Philodassiki Botanic Garden in Athens. Adjoining a monastery, this garden specialises in conserving plants unique to Mediterranean ecosystems, notably native mountainous plants thanks to the garden’s microclimate. Other gardens offer free entry, such as Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh and The National Botanic Gardens of Ireland in Dublin. The latter is operated as a public institution and aims to be “a place where leisure, recreation and education are all compatible for the enjoyment of visitors.” [10] Botanic gardens take many different forms and our model at Exeter is different again.

Our Model at the University of Exeter

What makes our botanic garden model unique is how the University’s botanic specimens can be found throughout the wider landscape, which is open access and free to enter. Among infrastructure, lie points of horticultural interest and scenic green spaces. Our gardens have grown around the University’s development.

The University was granted its Charter in 1955, but prior to this the land fell under the Streatham Estate. Planting schemes in the grounds of Streatham Hall (now known as Reed Hall) date back to the 1860s and were laid by the famed Veitch family of nurserymen [10]. Many of these plants were collected by the Lobb brothers and E. H. Wilson from many parts of the world. Many thousands of pounds were spent on laying out and improving the estate’s grounds, provided by Richard Thornton West (East India Merchant and owner of Streatham Hall) [10]. Reed Hall and the surrounding area is still a horticultural focal point of Streatham Campus and forms part of an impressive arboretum. The gardens of Reed Hall are of special historic interest, especially as much of the original Victorian design remains intact.

In 1922, Alderman W.H. Reed (former Mayor of the City) presented the house and gardens of Streatham Hall to the University College of the Southwest of England [25]. The College proceeded to purchase a major portion of the Streatham Estate. As such, in 1955 when the University formally came into existence, Exeter had one of the finest University sites in the country owing to the site’s horticultural interest and history. [25] Plans to create a botanic garden on-site were curtailed by the outbreak of the Second World War, though this was later re-visited with the planting of the Old Botanic Garden near the department of Botany’s laboratories, Hatherley building. [25]

In the mid-twentieth century, the site we know today was largely agricultural fields; since then the land has been developed extensively. Throughout the following decades, horticultural staff exploited the micro-climates which the buildings and natural undulations create, to grow tender and exotic plants such as Dicksonia (tree fern), Camellias and Magnolias. The southwest aspect of the campus and the rain shadow provided by Dartmoor National Park have also created conditions conducive to growing tender plants. As such, our horticultural specimens are found throughout a network of academic buildings. We didn’t inherit a traditional botanic garden structure – the plants and buildings have grown up around each other, making our layout quite different to traditional botanic gardens.

Our Custodial Responsibilities

International Standards

Over the next five years, the University of Exeter’s Grounds team endeavours to develop its role as a botanic garden, whilst continuing to maintain our campuses. Alongside our current work and projects, we are forming goals for the future. Both will involve engaging with the community here at the University, as well as with our peers in the horticultural world. Much of the existing work of the University’s Grounds team feeds into the acquired role as a botanic garden. This means that the accreditation is not adding any physical or financial pressure to the teams involved. In fact, it presents an exciting new opportunity to grow and expand current projects.

The guiding star when setting our goals is the ‘BGCI Botanic Garden Accreditation Standards Manual’. This manual sets “a global standard for botanic gardens.”, whilst being as inclusive as possible [19]. These standards must be met to gain and retain accreditation. Areas we must consider include horticultural collections maintenance and management, education, research and training initiatives, and conservation actions, to name a few.

Our Horticultural Collections

We are proud keepers of two accredited national collections. The first is of Azaras, a genus of trees and shrubs which are partially or fully evergreen with fragrant scented flowers and are native to South America. This collection can be found at the top of Streatham Campus near the Sports Park. Secondly, we are new keepers of the Dierama (angel fishing rods) national collection, which is situated on the Sir Steve Smith Building terrace. These are fascinating evergreen perennials with long grass-like leaves that grow from corms and are native to Africa. It is our responsibility to maintain, track and conserve these collections, as well as share them with others.

Other horticultural features across Streatham Campus include our Cacti and Succulent themed beds located at the Geoffrey Pope building (including recently planted nectar bar and dye beds) and the Cherry Orchard below Washington Singer. We host a collection of Rhododendron hardy hybrids behind the Business School. The ‘Old Botanic Garden’ near Queens Building contains a collection of interesting specimens planted after Queen Elizabeth II’s Diamond Jubilee in 2012. Several guided walks promote what our campuses have to offer and help to ‘join up the dots’. These include the Sculpture Walk, Sound Trail, Tree Trail, Jubilee Water Walk, Evolution Walk and Biodiversity Trail and are free to access year-round.

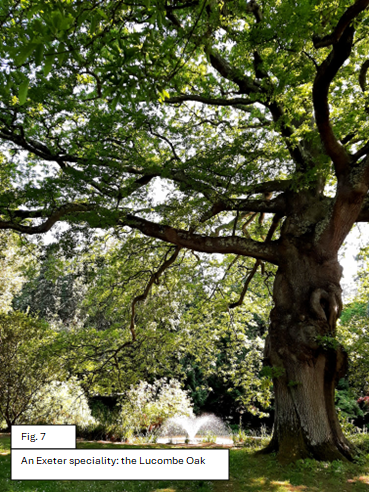

Arguably one of the biggest attractions to Streatham Campus is the collection of trees. The site hosts over 10,000 trees across 141 hectares [15] – an area of land equivalent to 141 rugby pitches! The historic Victorian arboretum found at Reed has been extended throughout the estate over the years, with plantings on Birks Bank, the Plantation and Taddiforde Valley. Horticultural highlights include Pinus coulteri (the ‘Big Cone Pine’) on Birks Bank and a collection of Magnolias in the Taddiforde Valley. This collection includes 1,000 Magnolia stellata and Cornus kousa. The current Grounds team will continue maintaining and expanding these arboreal collections.

As well as maintaining our plant collections, it is important to record them. In recent years, we have begun the process of digitising our plant records using the IrisBG database. With help from a small group of fantastic student interns, we have started to document our campus’ tree collection. This is a long-term project but has already begun to bear fruit. The digitising and mapping of our records will allow us to bring all the information into one place, safeguarding our records for the future and ensuring consistency for plant care. It will help us to provide reports and quantify our collections, ultimately making our plant collection information available for both practical and research purposes. The ambition of a publicly available map and seasonal guide forms part of this. Using IrisBG also allows us to track plant health, as we can log a plant’s ‘journey’ over time, such as any pests and diseases it has suffered, or any interventions such as translocation or heavy pruning. Long-term data collection can help tell stories about the landscape and will help track any patterns pertaining to climate change.

Education and Research

The Grounds team is part of such a talented, vibrant community here at Exeter and the opportunities to collaborate on research are wide and varied. We have and will continue to support student research projects with plant information and provision. Recent projects have included research in the fields of botany and horticulture, ecosystems and environmental change and psychology. Topics vary widely, such as plant evolution, plant photosynthesis and animal behaviour. The University of Exeter’s students are conducting vital research across all fields and the Grounds team aim to be involved with and support this as much as we reasonably can.

There are opportunities to collaborate with other botanic gardens and institutions in the future too. Examples include swapping seeds and/or plant material and collaborating on research – perhaps even in the future becoming a seed bank for other gardens. Our database and accreditation have made these real prospects.

An increasingly important role for botanic gardens is the monitoring of plant health. As the climate changes, plant pathogens alter in “distribution, abundance, and virulence”. Notably, “increasing temperatures might shift disease pressure geographically” [20]. An important way to manage this risk is to monitor plant health; as such, we are contributors to the International Plant Sentinel Network (IPSN), a “global [research] initiative dedicated to safeguarding plant health and promote plant biosecurity worldwide.” [16]. We are currently a monitoring station for Canker stain in Plane trees (Platanus), Holm Oak (Quercus ilex) and Hawthorn (Crataegus) health, with the view to continue and expand this in the future.

Educating our communities is of upmost importance. Through events (such as seed collection mornings) and campus tours, we would like to spread awareness about our goals for sustainable design. Part of this goal is low carbon, in-situ plant production for these planting schemes. In recent years, we have increased the number of plants we grow and propagate in our on-site nursery. These plants are then planted out onto our grounds, used for interior plants or sold at plant sales. In terms of plant production, the priority is maintaining and conserving the collection we have and adding to it over time via plant material or seed exchanges. For bigger project plantings, we buy seed and plugs in to grow on in our nursery. Houseplants are propagated in-house but occasionally bought in to add to variety of stock we have.

An exciting new project in recent years has been ‘The Kitchen Garden’ project in collaboration with the University’s Catering team. The Grounds team grow edibles to be used in on-site kitchens.[24] The project is in its early stages and plans are being developed to extend it. All plants for this project are grown from seeds and cuttings, with a focus on specialising in products that are better fresh (such as herbs, edible flowers, tomatoes and strawberries). The Grounds team’s Nursery Manager, Jess Evans, is passionate about education and the preservation of horticultural knowledge:

“Nurseries are vital for botanic gardens to conserve and expand the plant collection. It allows us to grow a range of plants that are not available commercially. Nursery work is also a vital horticultural skill for the Grounds team to experience”.

Horticulture as a profession is not only vital to the University, but also across the United Kingdom; it is a commercially important sector and a valuable (often unrecognised) career choice.

We are also in the process of redesigning and updating the various interpretation boards around campus. These boards highlight points of horticultural or ecological interest and include areas such as Reed Pond, the Streatham Court alpine collection and Higher Hoopern waterways. Enhancing visitor experience is key, as our campus hosts many visitors across the year.

Conservation Actions

The Grounds team is currently collaborating with the University’s Sustainability team to collate and merge biodiversity records with our plant records. We recently classified relevant trees on our IrisBG as Lepidoptera friendly. Knowing which plants support these flying insects (which include butterflies and moths) could lead to more informed planting plans in the future to support these species. The long view is to increase targeted, native planting and thus contributing to the University’s Nature Positive Strategy to enhance biodiversity by 2030.

We hope to develop our contribution to conservation and sustainability efforts, undertaking new projects in the future as well as building on current projects. One example is our ‘Edinburgh Collection’ on Streatham Campus – a wild conifer collection that supports the International Conifer Conservation Programme run by the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh. The programme is aimed at “safeguarding [conifers’] future[s] through both in-situ and ex-situ conservation efforts.” [21]. Our grounds act as an ex-situ living collection of various conifers, some of which are often threatened in the wild; they also provide an opportunity for research, public education and engagement. [22] Other on-campus conservation efforts include facilitating the implementation of bat detection stations and supporting the long-running bird surveys with help from our team members in species counting. [23]

Aspirations for the Future

Our recently reviewed ‘Plant Collections Policy’ will set the tone for how our collections are maintained and managed into the future. The policy covers the years 2025-2027 and aims to:

- Conserve both historic and contemporary flora, while also preserving native ecology

- Improve plant diversity on campus

- Increase the number of tree species present

- Increase the amount of native flora on campus, whether that is via planting new beds or integrating native planting into existing borders.

Anthony Cockell – Curator of Horticulture – is keen for the policy to be inclusive in its nature; in his own words:

“The goal is to evoke a ‘spirit of place’, especially as our campus welcomes people travelling from all over the globe. The familiarity or sense of home that a plant or space can invoke for a group or an individual is invaluable.”

Anthony is excited about our aspirations, but keen to focus on what the present offers;

“Our model is of a native garden that is a conservation bank for exotic plants but also rooted in the Devon landscape. We want to present something that other gardens can apply in their own situation, especially around accessibility.”

The vision takes inspiration from ‘environmental horticulture’, which is defined by the Royal Horticultural Society (RHS) as “a variety of activities, from cultivating ornamental plants to landscaping, arboriculture, and the design and upkeep of gardens, green spaces, and amenity trees”.[18]. The goal is to enhance these environments for both people and wildlife. The practical application of horticulture to benefit the wider community is important; as Anthony puts it,

“Our Grounds can be seen as a teaching resource. In the long run, we’d like to create opportunities that benefit the city and include its development, such as school visits”.

The University of Exeter grounds is a large green space very close to the city and transport links, meaning our botanic garden model is both accessible and dynamic.

As part of our strategy, we will become an ArbNet Accredited Arboretum – a programme which recognises “planning, governance, number of species, staff or volunteer support, education and public programming, and tree science research and conservation.” [17] Many of these goals overlap with ours and feed into our long-term goal to increase tree species numbers and varieties on campus. Alex Adams – Arboricultural Manager – believes the University’s trees need celebrating:

“The collection of trees we have on campus are massively undervalued. We hope we can start to make these available to other botanic gardens via our new tree nursery in the future”.

Above all else, the Grounds team has a responsibility to maintain and enhance the University grounds for all students, staff and visitors. As an accredited botanic garden, we look forward to continuing this work alongside our commitments to the BGCI’s international standards. Of upmost importance is how our green spaces can aid people with health and wellbeing. They provide relaxing spots for a whole host of things, be it revising for exams, or taking a ‘mindful moment’ away from the office. We are in the very early stages of our botanic garden journey and excited for what lies ahead.

Written by Lucy Forsey, Gardener on the University of Exeter’s Grounds Team

Links / Contacts:

- For information on the University of Exeter Grounds Team’s latest projects, please visit our Budding News blog Budding news – University of Exeter Grounds Team blog

- Streatham Campus highlights, walks and trails Horticultural highlights | Grounds and Gardens | University of Exeter

- Our Instagram page is kept up to date with the latest news University of Exeter Grounds (@universityofexetergrounds)

- You can access our entry on the BGCI website

- If you’d like to get in touch, please email us at grounds@exeter.ac.uk

References:

- BGCI (2025) wording from BGCI Botanic Garden Accreditation certificate

- Epic (2022) Botanic Gardens and Plant Conservation | Botanic Gardens Conservation International https://www.bgci.org/about/botanic-gardens-and-plant-conservation/

- Botanic gardens in Europe (no date) https://www.botanicalartandartists.com/botanic-gardens-in-europe.html

- It’s time to re-examine the history of botanical collections (no date) https://www.kew.org/read-and-watch/time-to-re-examine-the-history-of-botanical-collections

- BGCI GardenSearch (August 2025) https://gardensearch.bgci.org

- BGCI PlantSearch (August 2025) https://plantsearch.bgci.org

- The University of Exeter (no date) Streatham Campus Horticultural Highlights https://www.exeter.ac.uk/v8media/universityofexeter/campusservices/grounds/pdf/HH_Streatham_8th_Guide_Aug_2024_A4_CURRENT.pdf

- Wildwelshgardener (2023) Conservation and propagation of native Welsh plants at the National Botanic Garden of Wales

- Philodassiki Botanic Garden, BGCI GardenSearch (August 2025) https://gardensearch.bgci.org/garden/5464

- Role | National Botanic Gardens of Ireland (no date) https://www.botanicgardens.ie/glasnevin/role

- University of Exeter (2024) History | Grounds and Gardens | University of Exeter https://www.exeter.ac.uk/about/gardens/thegrounds/history

- THE GROUNDS OF EXETER UNIVERSITY (1955) A GUIDE TO THE GROUNDS. UNIVERSITY OF EXETER

- University of Exeter (2025) National Collection of Azara | Grounds and Gardens | University of Exeter https://www.exeter.ac.uk/about/gardens/thegrounds/nationalcollectionofazara

- University of Exeter (2024) Cherry orchard | Grounds and Gardens | University of Exeter https://www.exeter.ac.uk/about/gardens/thegrounds/cherryorchard

- University of Exeter (2024) Trees | Grounds and Gardens | University of Exeter https://www.exeter.ac.uk/about/gardens/thegrounds/trees

- Epic (2025) International Plant Sentinel Network | Botanic Gardens Conservation International https://www.bgci.org/our-work/networks/ipsn

- ARBNET | Accreditation (n.d.) https://www.arbnet.org/arboretum-accreditation-program

- Environmental Horticulture Group / RHS Gardening (no date) https://www.rhs.org.uk/science/environmental-horticulture-group

- BGCI Accreditation Botanic Garden Accreditation Standards Manual Version 2.0 (2022) BGCI https://www.bgci.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/BGA-Standards-Manual-2.0.pdf (accessed August 31, 2025)

- Huazhong Agricultural University (2024) ‘Effects of climate change on plant pathogens and host-pathogen interactions’ https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2773126X24000212?via%3Dihub

- International Conifer Conservation Programme | Genetics & Conservation (no date) https://www.rbge.org.uk/science-and-conservation/conservation-science/conifer-conservation

- Conifer ex-situ conservation (no date) https://www.rbge.org.uk/science-and-conservation/conservation-science/conifer-conservation/conifer-ex-situ-conservation

- University of Exeter (2024) Bird surveys | Grounds and Gardens | University of Exeter https://www.exeter.ac.uk/about/gardens/biodiversity/birdsurveys

- University of Exeter (2025) The Kitchen Garden | Eat and Shop | University of Exeter https://www.exeter.ac.uk/departments/campusservices/eatandshop/oureffect/kitchengarden

- Caldwell, J. and Proctor (1969) The Grounds and Gardens of the University of Exeter. Exeter, Devon, United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland: James Townsend and Sons Ltd

Images Credit:

- Forsey, L (June 2025) Wildflowers outside the Peter Chalk Centre, Streatham Campus, University of Exeter

- The Physic Garden, Chelsea: a plan view. Engraving by John Haynes, 1751 (no date) https://wellcomecollection.org/works/dhr7umzv

- Royal Botanic Gardens – marble drinking fountain in the entrance to Palm Cove c.1900 (no date) Museums of History New South Wales (@mhnsw) | Unsplash Photo Community https://unsplash.com/@mhnsw

- Forsey, L (May 2024) The Great Glasshouse at the National Botanic Garden Wales

- Forsey, L (2024) Reed Pond on Streatham Campus, University of Exeter

- Forsey, L (2024) Azara integrifolia ‘Variegata’, University of Exeter

- Forsey, L (May 2025) Lucombe Oak by Reed Pond, Streatham Campus, University of Exeter

- Forsey, L (2023) Seed collection event with staff and students on Streatham Campus, University of Exeter

- Forsey, L (May 2025) Rhododendron hybrids in bloom, Streatham Campus, University of Exeter

- Forsey, L (August 2025). Reed Pond information board, Streatham Campus, University of Exeter

- Forsey, L (April 2025) Laver Pond, Streatham Campus, University of Exeter