EcoPhysiology of Diving Air-breathing Predators – EcoDAP

EcoPhysiology of Diving Air-breathing Predators – EcoDAP

Climate change is affecting our whole planet. Polar ecosystems are changing much faster than other parts of the planet and we are seeing significant changes in the extent and seasonality of the sea ice. Yet, we still don’t understand how Antarctic seals, particularly those that depend on sea ice, are responding to this new environment.

Scientists from the University of Exeter, University of North Carolina Wilmington, University of California Santa Cruz, and the British Antarctic Survey are investigating the effects of climate change on the ecology of Antarctic ice seals, particularly crabeater seals. Crabeater seals prey almost exclusively on Antarctic krill, a keystone prey species for predators ranging from fish to large whales. By investigating how seals are responding to climatic changes to sea ice and changes in krill habitat distribution, we can learn about the health of the entire Antarctic ecosystem. With sea ice retreating and krill habitat changing, scientists are gathering Antarctic seal sightings to better our understanding of their habitat usage in this changing habitat.

It’s as simple as sharing your photos.

We are looking for photos of Antarctic seals hauled out on ice floes (individuals or groups), including the surrounding area (sea ice, open water), as well as the date, location and any other pertinent information (weather, behaviour, other species in the area). Use your camera’s built-in GPS for location, if possible (not required, location info can be taken from other reliable sources).

n order to qualitatively analyze the images you submit, it is essential to send images that show the animal’s profile (side view) and body. If there are several seals congregated together, take one large group photo and several zoomed in images in order to aid our species identification.

There are 6 seal species that live in the Antarctic. Learn more about each species and how to identify them!

Every year, seals shed their fur, undergoing a process called “moulting”. The freshly moulted crabeater seal coat has a rich sheen, and can range in colour from silvery grey to tawny brown. As time progresses from the moult, crabeater seal pelage fades dramatically, becoming light tan, pale grey, or whitish. The head and muzzle are moderately long and slender relative to the animal’s length. The eyes are set well apart, and the head tapers to the base of the straight-sided muzzle, forming a small but distinguishable forehead, unlike Leopard seals. The foreflippers are medium-length, measuring about one-fourth of the animal’s body length. Many crabeater seals bear long dark scars that have been attributed to attacks by leopard seals or intraspecific (same species) fighting.

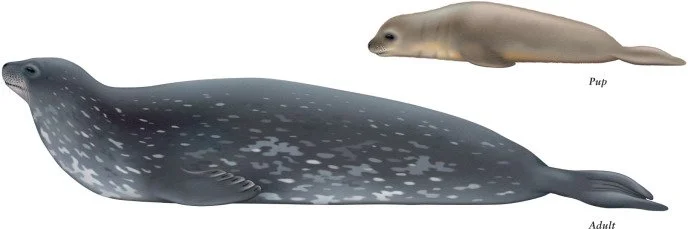

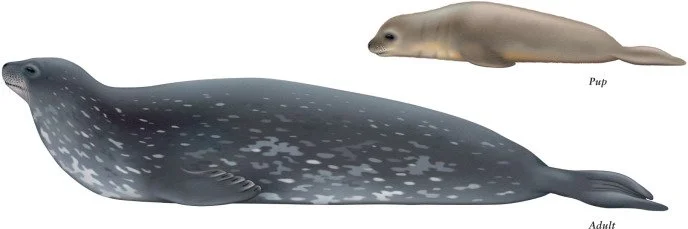

Leopard seals have massive heads, long jaws, and broad U-shaped muzzles, making them appear almost reptilian. The body is spotted, and the pelage is consistently dark on the top and light on the bottom, otherwise known as countershading. The body is long and thin, approximately 3 meters. The foreflippers are also exceptionally long, almost one-third of the animal’s body length. The foreflippers are situated farther back on the body from the muzzle than on other Antarctic seals, creating a long neck.

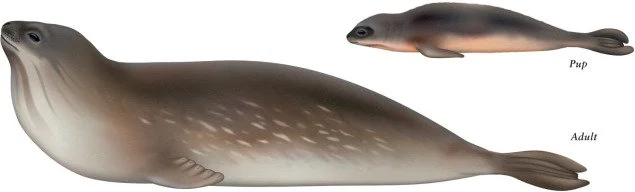

Weddell seals have very short and blunt rostrums, large and close-set eyes, and a mouthline that is turned upwards at the corners. The foreflippers are pointed and angular, and are proportionately shorter than all other Antarctic seals. Adults are dark silver-grey on top and off-white bottom with various spotting and streaking across the pelage. The muzzle and eyes tend to have white crescent markings around them.

Ross seals are typically counter-shaded, blending along the sides, in colours that range from dark brown to dark grey and black. Most striking are a series of dark streaks, unique to this pinniped, originating from the face and extending down the neck and sides. Scars are often seen on the neck, possibly from intraspecific fighting, and a small percentage of animals have scars from wounds believed to be from leopard seals or killer whale attacks. Pups are born in a two-toned lanugo that is dark brown to blackish above and lighter grey, yellowish below. The head and neck are thick and wide, while the rest of the body appears proportionately short and slender. The muzzle and mouth are short and wide, giving the end of the head a blunt appearance.

The largest pinniped species in the world. Both sexes exhibit robust bodies and very thick necks. The head, rostrum, and lower jaw are all broad, and in females and juveniles in particular, the rostrum is short. Adult males are easy to identify with their long and enlarged nose (proboscis), which is inflatable and used to make loud roaring noises during mating season. All adults have an unspotted pelage ranging from light to dark grey or tan to dark brown. Often, this pelage becomes stained a rusty orange and brown colour from lying in their excrement.

Antarctic fur seals show strong sexual dimorphism, with adult males 4–5 times the mass and 1.4–1.5 times the length of adult females. The muzzle is of medium length and width, straight, tapering to a pointed end, making the head look almost American football-shaped. Unlike other Antarctic seals, they have external ear flaps. The ear flaps (pinnae) are long, prominent, and pale in colour with lighter tips. Adult males have the longest vibrissae (whiskers) of any other pinniped. In older adult males, the neck and shoulders are also greatly enlarged with fat and the development of muscles. Pale colour extends from the chest variably up the neck, to as high as the throat, eyes, and muzzle. The dark fur on the top of the foreflippers extends into the area where the foreflipper inserts at the shoulder.

All of the above scientific illustrations were created by Uko Gorter and used in Marine Mammals of the World, Second Edition (2015)