Matilda Nightingale, a Postgraduate Researcher in English and Creative Writing at the University of Exeter, takes us inside the hidden costs of Victorian fashion.

My work explores the hidden environmental and human killers behind Victorian household goods. My research begins with the corset, an iconic and beautiful object of the 19th century, and examines it to investigate the global networks of extraction, labour, and exploitation that enabled the British fashion industry to flourish.

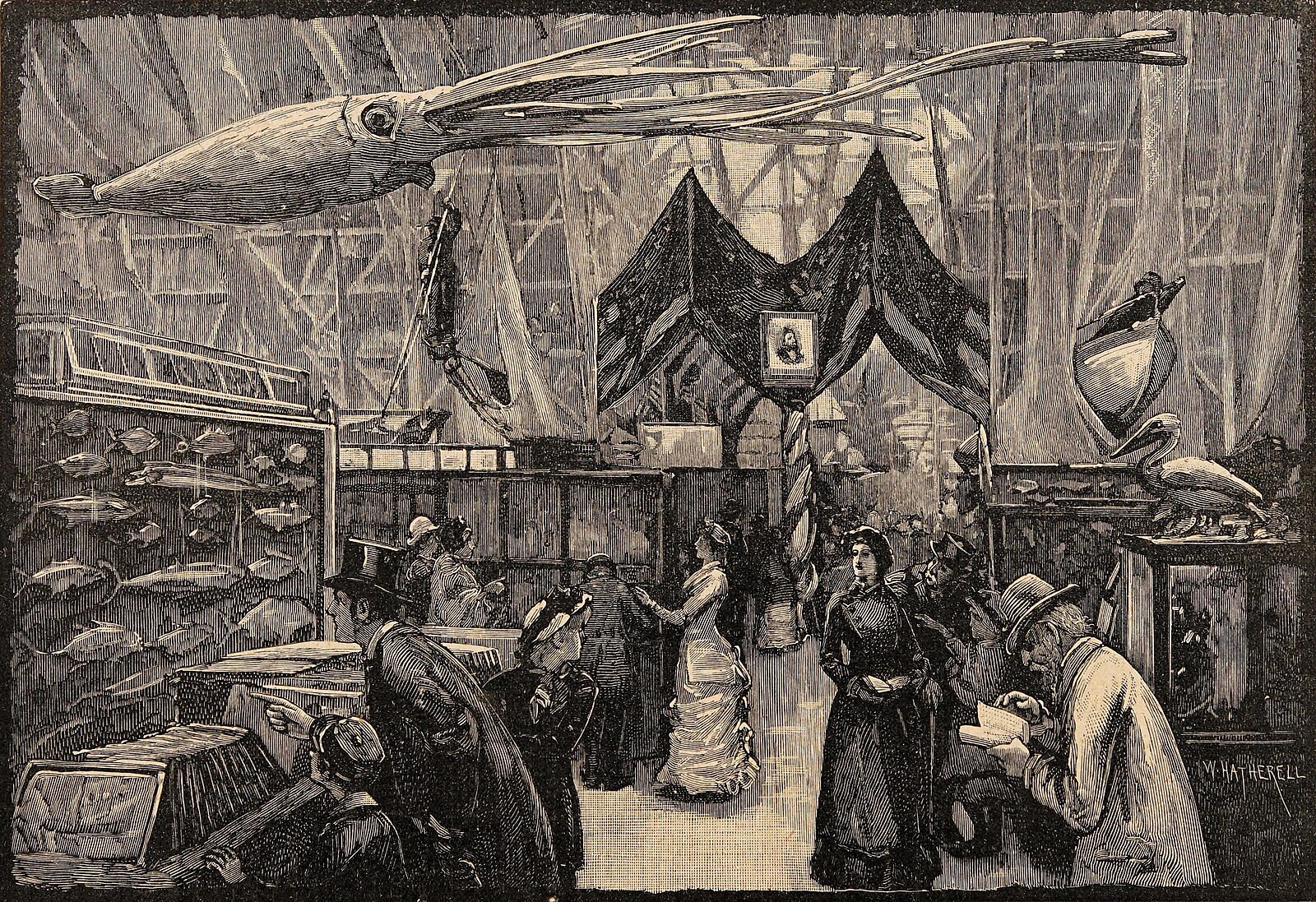

One of my research projects took me to investigate the 1883 International Fisheries Exhibition, a trade fair that promoted Britain’s mastery over the seas. The exhibition transformed the Royal Horticultural Society grounds in South Kensington into a celebration of Victorian innovation. With its vast tanks of live sea life, ornate pavilions from across 31 nations, and a record 2.6 million visitors, the exhibition was a marvel of spectacle and fishing. But beneath the surface of this grand showcase lay a darker story — one I’ve been exploring for my PGR research. Among its many exhibits was industrial whaling — framed not as ecological devastation, but as imperial ingenuity and dominance. Visitors encountered full-sized whaleboats, gun harpoons, lances, skeletons, and a collection of whalebone goods. Luxurious corsets, crinolines, buggy whips, parasols, and even fishing rods were all made from the baleen of whales — dried, softened and cut into flexible strips that shaped both women’s bodies and Britain’s vision of global superiority.

But while the tools of whaling were proudly on display, the violence they represented was carefully hidden. Harpoons, lances and cutting gear were exhibited not as instruments of death, but as triumphs of engineering. There was no mourning of the whales, no signs of blood or struggle — just the clean success of the British Empire. The brutality of whaling wasn’t entirely absent; it was hiding in plain sight, dressed up as progress. Whales were considered alien, distant living creatures which were not domesticated; hence no one raised concerns around their exploitation and commodification.

Both fishing and fashion industries took central part in the ecological degradation of baleen whales and turned them into a performance of national pride. There was no mention of dwindling whale populations, of oceanic ecosystems pushed to the brink, or of the brutal conditions faced by whalers themselves. Instead, the whale was made into a luxurious and necessary commodity to purchase. Visitors were invited to marvel at what British industry could extract, process, and sell, not to question the cost.

This blog post is a small window into the research process I’m currently immersed in. Alongside archival work, I’ve been exploring visual culture — examining Victorian fashion plates, museum collections, and exhibition catalogues. I’ve also been tracing the movement of materials across empires: whalebone from the Arctic Sea, whalebone processing factories, corset factories before reaching women’s wardrobes. Each object, no matter how elegant, reveals a network of environmental and human exploitation.

The 1883 Fisheries Exhibition is a focal point in my research to understand how these networks were displayed — and concealed. It turned violence into spectacle. It taught its visitors not to look away from exploitation, but to accept it in their daily lives.

My hope is that by exposing the hidden costs of Victorian fashion, we can better understand the long shadow it casts over our present.

I have always been keen to publish my work and engage with the public about hidden narratives. I wrote for the Historian Magazine on Aethelflaed; Lady of the Mercians and the Matchstick girls in Victorian England. Last year, I had the privilege of having my article “A Bodice-ripping revolution: how Victorian women cast off deadly fashion trends” published by BBC History Extra Magazine. It explored the hidden health risks of tightlacing and the cultural, physical and emotional pressures surrounding femininity. But the more I researched corsets, the more I realised that these hazards weren’t just personal — they were global. The same corsets that impacted women’s ribs and internal organs and their ability to perform daily activities were also integral to the rupture of ecosystems. Whalebone was a crucial raw material in Victorian fashion, and it came at the cost of the depletion of whale populations and environmental degradation.

Image: The US display at the International Fisheries Exhibition of 1883, held in London, UK. A model of a giant squid (Architeuthis), made by J. H. Emerton and A. E. Verrill for the Smithsonian, is seen hanging in the background. Hatherell, W., Cassell’s History of England, vol. 7, 1903, p. 600

Matilda Nightingale is a public historian with thirteen years of curatorial experience, focusing on Tudor, Medieval and Victorian culture, fashion, and social history. She is a first year PhD student in the English and Creative Writing Faculty at the University of Exeter. Her research is on ‘Victorian Hazards: Curatorial Practice, Cultural History and the Legacy of Empire’. She aims to examine the hidden narratives of five Victorian household goods. It situates these objects within the contexts of imperialism, global expansion, and environmental degradation, analysing the hazardous substances they contained and their societal and cultural implications.

The project also aims to develop responsible curation strategies for museums, encouraging open dialogue about shared histories. By using interdisciplinary approaches and innovative methodologies, Matilda seeks to bridge academia and the cultural sector, fostering accessible, inclusive, and sustainable practices that deepen public engagement with the past.