The History MA at the University of Exeter

The History MA at the University of Exeter

As part of the Historical Masterclass module, you will choose one Masterclass option. Each option is a unique opportunity to learn from and work alongside an academic in their specialist area of research, and will allow you to explore a specific subject at a level of depth and expertise only possible here at Exeter. The list of Historical Masterclass options is always changing, reflecting the evolving nature of our research, but you can find some examples of Historical Masterclass options below.

Why are we interested in the history of sexuality? What is the purpose of queer history? What is the relationship between historical research and contemporary sexual politics?

In this masterclass option we will explore the history of the relationship between research into the history sexuality and movements for sex reform. We will explore these themes through a series of case studies. These could include how sexual scientists in the early 1900s spearheaded attempts to legalise homosexuality. Or, how different interpretations of historical gender non-conformity feeds antagonisms between ‘gender critical’ feminists (TERFS) and advocates for transgender rights.

These cases raise important questions about the politics at stake in approaches to the history of sexuality and our civic responsibilities as historians. What is at stake in finding, recognising, or interpreting the sexual lives of people in the past? How can we understand the past sexualities without imposing our own categories on people’s experiences? Do historicising approaches make our queer ancestors invisible or alien? Is there a tension between rigorous and theoretically complex historical practice, public history, democratic history and the needs of marginalised communities? What is it to be a historian of sexuality committed to addressing inequalities and social injustices in the present?

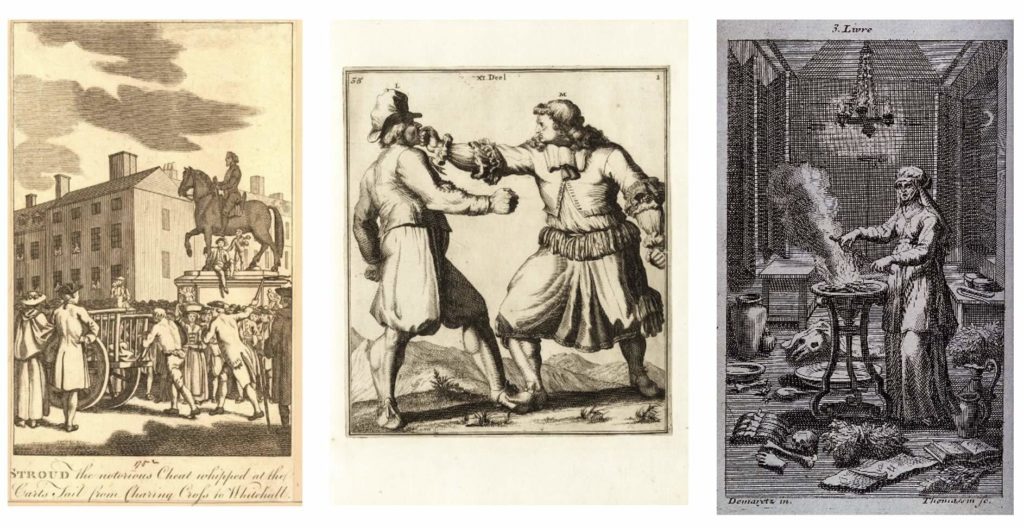

The early modern period has been characterised as one that was rife with violence, whether from ongoing warfare, judicial violence with severe punishments including execution (sometimes in particularly violent and gory ways), interpersonal violence, whether through duelling, brawling, chastisement of servants, apprentices and children, or other domestic violence between spouses, sexual violence, and racial violence in slave transportation and plantations. This masterclass explores the many and varied sites of violence in the early modern world, with a particular focus on England. The early modern period has also been represented as a transitional period in which rapid changes were taking place, including in attitudes towards violence, so that by the early eighteenth century violence was beginning to be considered less acceptable and virtues of politeness and restraint were making themselves felt. This masterclass will interrogate the many different forms of violence and attitudes towards them from the sixteenth century through to the early eighteenth considering how far it is possible to detect changes in both ways of thinking and reactions to violent occurrences in a range of contexts.

On 1 March 1881, a group of Russian revolutionaries assassinated Tsar Alexander II – an event that sent shockwaves across Europe and which marked, in effect, the birth of modern political terrorism as we know it today. Two decades later, terrorism returned to Russia with a vengeance: in the years of the ‘first Russian Revolution’ (1905-1907), Russian society was rocked by an unprecedented wave of political violence from the left (and, in return, from the government) that claimed thousands of lives. This masterclass option will examine the origins of revolutionary terrorism in Russia and its impact on the history of the Russian Revolution. Drawing on a wide range of sources and methodologies, our sessions will address several key questions. Why did Russian socialists turn to violence in the first place? How did the parties of the left understand terrorism ideologically and politically, and how did the terrorists themselves address the moral dilemmas it presented? How did the Tsarist regime, and wider Russian society, respond to the terrorist threat? In asking these questions, and by examining the wider transnational and transhistorical implications of terror, its mythologies and cultural representations, the masterclass option will seek to consider what terrorism ‘then’ may be able to tell us about terrorism ‘now’.

No knowledge of Russian is required: all readings are available in English.

Over the past 30 years, a mass of historical materials – from documents and newspapers to objects and paintings – have been digitised and made available online. Such “digital archives” are now a common feature of historical research. Whether it’s Google Books, Gale Primary Sources or the British Library Manuscripts Online, all historians now use digital archives at some point in their research. Yet they have often done so uncritically. Like any primary source, we need to ask how and why these digital archives came into being. Why do we digitise? Who gets to decide what gets digitised? How are historical materials digitised? And what opportunities and challenges do digital archives pose for historians? In this Masterclass option we will consider these issues, drawing on recent scholarship and the Exeter Digital Humanities Lab’s substantial expertise in this area. No specialist technical knowledge or skills are needed to take this Masterclass option, and whilst there will be opportunities for you to get training in digitisation methods if you wish, this isn’t a compulsory part of the course. The Masterclass will develop your critical understanding of, and skills in using, digital archives, which will be invaluable for your own research, and it will be useful for anyone considering a career in Heritage.

Should the streets be a stage for collective political action? Ever since newly emerging social movements started to employ marches and rallies to promote their views and goals in the nineteenth century, the right to contentious political action in public spaces has been negotiated, contested, and restricted. What some observers praised as the unfiltered expression of the will of the people, a form of plebiscite, or indicator of a vibrant civil society appeared to others as organised mob pressure and prelude to unrest or revolution. The limits of legitimate protest and appropriate ways of policing crowds continued to be debated even after the right to collective public protest was enshrined in the UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948, and the discussion continues in Britain as well as many other countries.

In this masterclass option we will explore the long struggle to establish and defend the right to collective street protest in Western Europe and the United States from the nineteenth century to the present. We will discuss central concepts, theoretical approaches, and tactics, and study a range of seminal marches which were turning points in the long history of political demonstrations.

Revolutions have been one of the most influential processes in the development of the modern world, reshaping political structures, disrupting social hierarchies, instigating new economic practices, and inspiring innovative cultural practices. For many years, scholars focused on the tangible factors that shaped revolutionary processes, from political repression and regime breakdown to social aspirations and economic grievances. Revolutions, though, are also about less tangible factors, and the way that revolutions have been framed linguistically, the words used to express ambitions and fears, and the new categories prompted by revolutionary change have played a central part in the nature and outcomes of revolutions. This masterclass option explores the many ways that language has shaped the revolutionary process, starting with the significance of categorising an event as a ‘revolution’ in the first place before interrogating the competing languages of change, contestation and counter-revolution that provide the incendiary dynamics that fuel revolutionary processes. While focusing on the interdisciplinary work that has built up around the ‘classic’ revolutions – most obviously, France, Russia, China and Iran – this masterclass takes a broad approach wherever possible, providing opportunities to examine revolutionary change across the globe from the late eighteenth century to the present day.

On 15th February 1865, the body of a young boy was discovered abandoned on the outskirts of Torquay in Devon. Having identified the child as three-month-old Thomas Harris, local police arrested the child’s mother, Mary Jane Harris, and his nurse, Charlotte Winsor, and charged them both with murder. When the two women were first tried in March 1865, the jury failed to reach a verdict. At the second trial later that year, Mary turned Queen’s evidence and Charlotte was convicted of murder and sentenced to death.

The Torquay murder coincided with a national infanticide crisis. According to doctors and investigative journalists, during the 1860s thousands of infants were being killed by unmarried mothers to avoid the shame and burden of bearing and caring for illegitimate children. Even if the child lived, nurses – or `baby-farmers’ – were thought to be neglecting or murdering children in their care. By intensifying public outrage at high levels of infant mortality, the Torquay murder and subsequent baby-farming scandals triggered debates about reforming harsh bastardy and poor laws, protecting infant life and regulating the practice of paid child-care and adoption, particularly in working-class communities.

Highlighting the rich range of original sources available to study the history of crime and medicine – inquest reports, court records, witness depositions, newspaper accounts, census records, medical and legal texts, novels, letters, Home Office documents and prison and hospital records – as well as a wide secondary literature, this module will explore attitudes to working women, absent fathers, illegitimacy, child-care, medical authority and political expediency from the mid-nineteenth century through to the Adoption Act of 1926.

The story of modern Britain is still often told as the progress toward ever greater freedom. At the heart of this tale is a mistaken but stubborn narrative about work, in which medieval serfs and then enslaved Africans were replaced by ‘free’ wage workers. Yet unfree labour takes many forms and has always existed in tandem with free labour up until the present day, precluding any attempt to consign it to a ‘premodern’ stage in economic development. This masterclass option explores the diverse forms of unfree labour that coexisted across Britain and its empire from the late sixteenth to the early nineteenth century, and considers their combined role in shaping modern capitalism.

In England, strict labour laws enshrined by statute in 1563 compelled the poor, the young and the marginalised into service, enforcing labour discipline with the threat of criminal punishments. As the British Empire expanded through conquest, it developed new forms of bonded labour in its colonies, from indentured servitude to the racialised system of plantation slavery. This masterclass considers the similarities and differences among these types of coerced labour coded by gender, race, age and class, comparing the mechanisms of domination, experiences of coercion, and acts of resistance. It draws upon vibrant new scholarship on global labour history and uses an array of primary sources to examine the concept of ‘free’ labour from cultural, legal and economic perspectives.

In a searing denunciation of colonial rule published at the height of the Algerian war of independence, Frantz Fanon famously characterised colonialism as ‘a fertile purveyor for psychiatric hospitals’. This tutorial explores the many and varied entanglements between madness and empire in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries. As European empires expanded to reach their greatest extent, the discipline of psychiatry travelled too, and was transformed in the process. Pressed into service as a language with which to construct colonial subjects as an inferior ‘other’, within asylum walls psychiatry found itself grappling with questions of race, gender, and class in new and radically unequal contexts. With the emergence of Indian, Egyptian, and Nigerian psychiatrists and psychoanalysts, the sciences of the mind began to look less like an alibi of empire and more like a means to critique it. Through the lens of social, political, and intellectual history, and drawing on recent scholarship and key primary texts, this tutorial interrogates the place of madness in a colonial, decolonising, and postcolonial world.

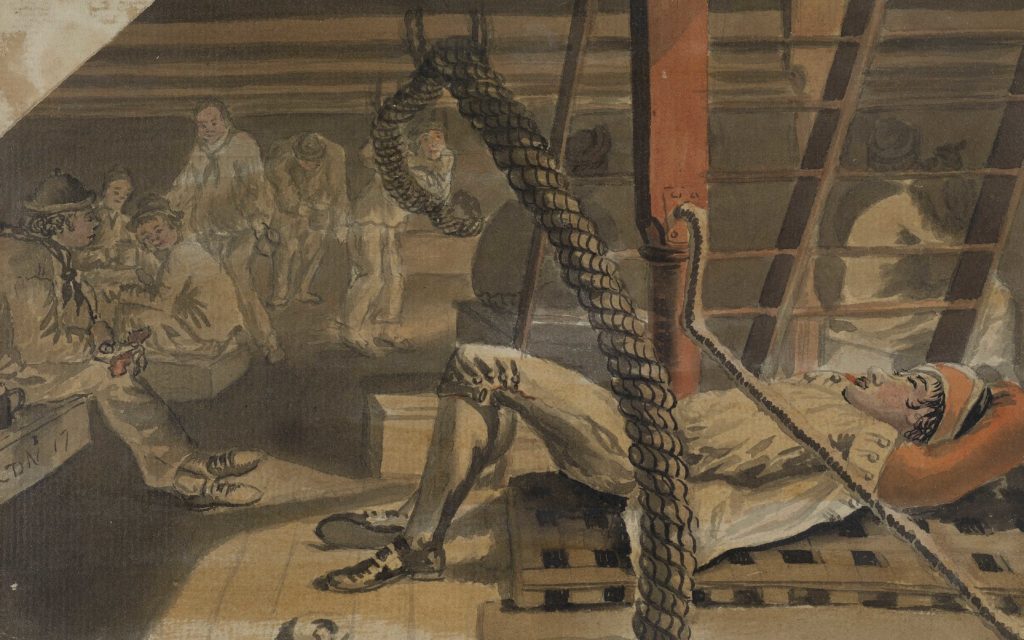

From global trade and warfare to the migration of knowledge and communities, maritime history is undergoing an academic resurgence as scholars uncover new perspectives on humankind’s relationship to the sea. Central to this revival has been the drive to study the maritime world ‘from below’; that is, to examine and analyse ordinary people who lived, worked and recreated on the oceans. There has been a proliferation of studies on sailors, transported prisoners, enslaved people, lascars, smugglers and pirates, all of which has contributed to a new maritime history that is inclusive, inter-disciplinary, and closely engaged with contemporary scholarship.

A key reason for this change is a growing appreciation of the rich – but largely untapped – source base available to those who study the maritime world. Navies, merchant houses and customs officials kept incredibly detailed records, offering treasure troves of source material on seaborne lives. At the same time, by examining naval courts martial, protest songs and petitions, we can explore the agendas of previously hidden historical actors, and sometimes recover their voices directly. Much work remains to be done, however, and you can be part of it!

This masterclass prepares you to embark on your own voyage of historical discovery. We will explore how studying maritime history ‘from below’ can offer unique insights into the history of ideas, work, violence, resistance and empire, and discuss some of the key works at the forefront of this movement. You will then be encouraged to craft your own research project that uses a discrete body of source material to construct an original piece of historical scholarship.