Posted by ccld201

13 March 2024On March 4th, France became the first country in the world to protect a woman’s right to abortion explicitly in the text of the Constitution. By an extraordinarily lopsided margin of 780 votes to 72, the French Parliament convened in Versailles approved constitutional language that guarantees the liberty of women to choose to interrupt a pregnancy. The new Article 34 of the 1958 Constitution says: “The law determines the conditions by which is exercised the freedom of women to voluntarily terminate a pregnancy, which is guaranteed.”[1]

The practical effect of the constitutional amendment is not clear, since women have had the right, since 1975, to terminate their pregnancy; current law protects abortion up to 14 weeks, “with the cost of the procedure covered by the national health insurance system,” according to Euronews. The constitutional change neither extends nor contracts that right nor changes public support for the procedure.

But entrenchment in the constitutional text does two important things.

First, it ensures that the right remains protected, immunizing it from the political whims of legislators who would otherwise have the power to restrict the right merely by changing the law. While the amendment was viewed by many in France as unnecessary given wide support for abortion rights, the overturning of abortion rights in the United States and political shifts in Hungary have emphasized the current reality that rights are never quite as secure as they seem.

It is worth noting, though, that abortion rights have never been the political football in France that they have been in the United States, where politicians and judges have for decades sought to score political points at the expense of women. In the US, the right espouses white nationalist immigration policies and denounces measures designed to promote diversity and inclusivity, and at the same time attacks access to health care, rights relating to gender and sexual identity and personal liberty, intellectual freedom, and more – including the very foundations of the administrative state, and of course, democracy itself. But the political landscape in France is far different. In France, the people’s rights to live with dignity is part of the fabric of living in a social state; as such the right to health care including reproductive health care has not been at risk. That is perhaps why the support for this constitutional change was so broad, despite an otherwise fractured and precarious body politic.

So perhaps it is the second impact of the new constitutional language that is most important. This is the rhetorical and narrative power of constitutional texts. A guarantee in the constitution affirms the significance, within each society, of the right at issue. For instance, the second amendment in the United States announces to the world that private ownership of firearms is valued; indeed, as the Supreme Court would say, it is part of the history and tradition of the United States. Constitutions in other countries that protect the right to health care, to housing, to education, to a healthy environment, to freedom of expression, or indeed to human dignity itself say that those values are imperative. In some instances, such rights can be inviolable and absolute, but even where they are not, they are to be treated with utmost respect and restrictions on such rights can be justified only in very limited circumstances. This can, of course, be done without an explicit reference in the constitutional text, if courts interpret the text as suggesting or permitting the protection of a particular right. But France’s recent action is premised on the belief that it is invariably better when the constitutional text is explicit, leaving no room for interpretive quibbling.

And the timing of France’s action reinforces its rhetorical impact. There is no doubt that the French took action in large part to rebuke the United States Supreme Court decision that threw reproductive rights into the political fray. While France is the first country to do so by amending the constitutional text itself, other countries have redoubled their efforts to protect women’s right to choose through constitutional interpretation, notably by interpreting the right to dignity to include a woman’s right to bodily integrity and to make decisions that are essential to her own life project without interference.

Just a few months after Dobbs, the Indian Supreme Court explained that “The right to dignity encapsulates the right of every individual to be treated as a self-governing entity having intrinsic value. It means that every human being possesses dignity merely by being a human, and can make self-defining and self- determining choices.”[2] The Court then applied these principles to the situation of a person who seeks to end a pregnancy: “If women with unwanted pregnancies are forced to carry their pregnancies to term, the state would be stripping them of the right to determine the immediate and long-term path their lives would take. Depriving women of autonomy not only over their bodies but also over their lives would be an affront to their dignity.”

A few months after that, the Mexican Supreme Court did the same thing. “Human dignity is not just a simple ethical declaration, but consecrates a fundamental personal right which imposes on every governmental authority a mandate to respect and protect the dignity of every human being, understood – in its essence – as the inherent interest of each individual, by the mere fact of being a human being, to be treated as such and not as an object, to not be humiliated, degraded, debased, or objectified.”[3] Human dignity, the court said, recognizes the particularities of pregnancy and is founded in the idea that “women and people with the capacity to gestate can freely use their bodies and can develop their identities and their destinies autonomously, free of obstacles, which is part of recognizing the elements that define them and the exercise of their rights necessary for the full development of their life.”[4]

Locating the right to abortion in human dignity has several important implications.

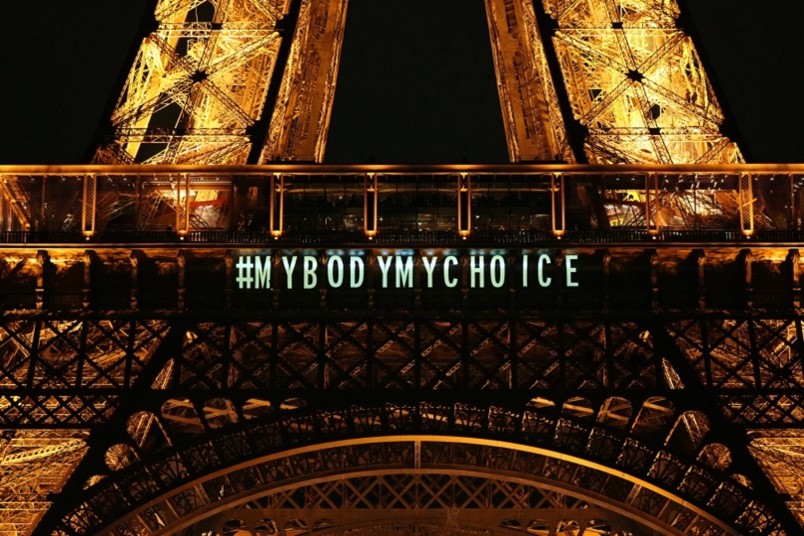

First, it makes it clear that abortion is an essential part of reproductive health care that must be exercised by the person affected and only by her. Dignity, as these courts explain, is matter of bodily integrity and self-determination. Or, as the Eiffel Tower proclaimed, “mon corps, mon choix” – in French and in English, so that the message wouldn’t be lost on Americans looking longingly across the Atlantic.

Second, dignity entails the equal status of all people, and locating the right to choose in women’s dignity recognizes that pregnancy does not justify limiting women’s rights to make decisions about their own lives, to control their bodies, or to protect their privacy. Women, like men, should always have the ability to fully develop their personalities, to control their lives, and to make decisions for themselves, just as men do and have always done.

And, third, as with the French constitutional amendment, this does not make the right to abortion absolute for all 9 months of pregnancy, but it does insist that whatever restrictions are imposed are consistent with the core values of human dignity. Dignity in many countries is a non-derogable right – since there is never a justification for violating a person’s dignity; rather, any competing governmental interests must be accomplished in ways that respect human dignity. This applies to the balancing that must be done in the criminal justice system, in the provision of social rights, and throughout a nation’s politic, and likewise with reproductive rights. Any countervailing interest the state has must be aligned with every person’s inherent dignity. Allowing women’s dignity to be compromised for any reason (including a state’s asserted interest in protecting the potentiality of embryonic or fetal life), reduces women’s agency and their status as equal members of society.

This has been recognized even in the United States, although at the subnational level. In November 2022, just 5 months after the Dobbs decision, voters in Vermont amended their constitution by 77% to 23% to protect the dignity of abortion rights. The text reads:

That an individual’s right to personal reproductive autonomy is central to the liberty and dignity to determine one’s own life course and shall not be denied or infringed unless justified by a compelling State interest achieved by the least restrictive means.[5]

While the decision by the US Supreme Court has immeasurably hurt tens of millions of American women, it may have had a galvanizing effect of protecting the dignity right to abortion of many hundreds of millions more in countries throughout the world.

Erin Daly is Professor of Law at Widener University Delaware Law School, where she directs the Dignity Rights Clinic. She is the author of numerous books about dignity law, including Dignity Rights: Courts, Constitutions, and the Worth of the Human Person (2020).

[1] https://www.lemonde.fr/en/politics/article/2024/03/05/france-protecting-abortion-in-its-constitution-sends-message-to-women-of-the-world_6586538_5.html#:~:text=%22The%20law%20determines%20the%20conditions,Constitution%20now%20includes%20this%20section.

[2] X v. The Principal Secretary, Health and Family Welfare Department, Govt. of NCT of Delhi & Anr., Civil Appeal No 5802 of 2022 (Arising out of SLP (C) No 12612 of 2022) (Supreme Court of India, September 2022), at para. 109.

[3] At para 35.

[4] Id. at para. 38.

[5] Vermont Constitution. Article 22. [Personal reproductive liberty]