The label ‘Anglo-French’ (found in our project title) may be unfamiliar to readers. When pressed, we usually define ‘Anglo-French’ as the French language as used in Britain in the centuries following the Norman Conquest, but it is worth noting that the terminology to describe this distinctive variety of French is far from uniform.

Users of French in medieval Britain typically describe the language that they use as either français (‘French’) or romanz (‘Romance’). In academic circles, however, the predominant term used to describe the form of French used in the British Isles during the medieval period has, since the 19th century, been ‘Anglo-Norman’. The term has a strong institutional pedigree, associated with both the Anglo-Norman Text Society (which publishes editions of texts in French from medieval Britain) and the closely-related Anglo-Norman Dictionary. In the first half of the twentieth century, ‘Anglo-Norman’ was occasionally used to refer specifically to French from the Norman Conquest to the loss of Normandy to the Kingdom of France in 1204, with the term ‘Anglo-French’ used to designate the language as used after the events of 1204. On this account, ‘Anglo-French’ was characterised by a greater degree of influence from continental French dialects, in keeping with the received wisdom that the language rapidly ossified and declined in use in Britain from the thirteenth century onwards.

Recent years, however, have seen a wholesale reassessment of the status of French in later medieval Britain, as the corpus of sources discussed by historians and linguists has expanded beyond literary works to pay greater attention to administrative, diplomatic, didactic, and legal texts. The language of decline and demise has largely been abandoned. Instead, current research broadly agrees on three principles:

New paradigms call forth new terminologies, and questions have been raised about the implications of ‘Anglo-Norman’ as an umbrella term. Specifically, it implies a privileged relationship withthe Norman dialect, with the British variety an isolated descendant, distanced from other Continental dialects. This model reinforces unhelpful ideas about its supposed eccentricity and places undue emphasis on the Conquest and its aftermath, rather than the subsequent centuries in which the bulk of surviving texts were produced. Thus, while many scholars have been happy to extend the label ‘Anglo-Norman’ to the whole medieval period, others have felt the need to search for alternative terminology.

In this spirit, a 2009 chapter by Jocelyn Wogan-Browne coined the term ‘French of England’ to ‘embrace medieval francophony in England, from the eleventh century to the fifteenth’ in a way that tied it more clearly to the full linguistic spectrum of the francophone world. Nevertheless, as Wogan-Browne herself acknowledges, talking about ‘the French of England’ runs the risk of overlooking its use in Scotland, Ireland and Wales. Indeed, the use of the language in these regions has begun to see sustained attention in recent years.

Another term found in scholarship, which may appear to sidestep the overemphasis on England, is ‘Insular French’. Yet this name may be swapping one problem for another: while more capacious in acknowledging the language’s use across the British Isles, both literally and connotationally it threatens to reinforce the old unhelpful idea of its exceptionality with regard to Continental dialects. (Moreover, it may itself obscure differences in the uses and values of French across different regions of the British Isles, an issue that is only now beginning to be considered in scholarship

We make no pretence that Anglo-French is a perfect solution to the question of terminology. It suffers to an extent from some of the objections to French of England and Insular French discussed above. Nevertheless, we adopt it as an acceptable compromise between accuracy (it designates a dialect of French whose particularities derive in large part from contact with English), intelligibility (its scope is immediately graspable) and convenience (it is quick to write and read).

Our conception of the competing terms – Anglo-Norman’, ‘Anglo-French’, ‘ Insular French’ and ‘the French of England’ – is that they can be used and understood largely interchangeably. In a recent review of a volume of essays entitled The French of Medieval England, Ardis Butterfield stresses that ‘terms, especially retrospective ones, are partial and provisional, and there is no point insisting on only one.’ In a similar vein, we hope that our term of choice — Anglo-French — will be understood as a statement of open dialogue rather than of dogmatic conviction.

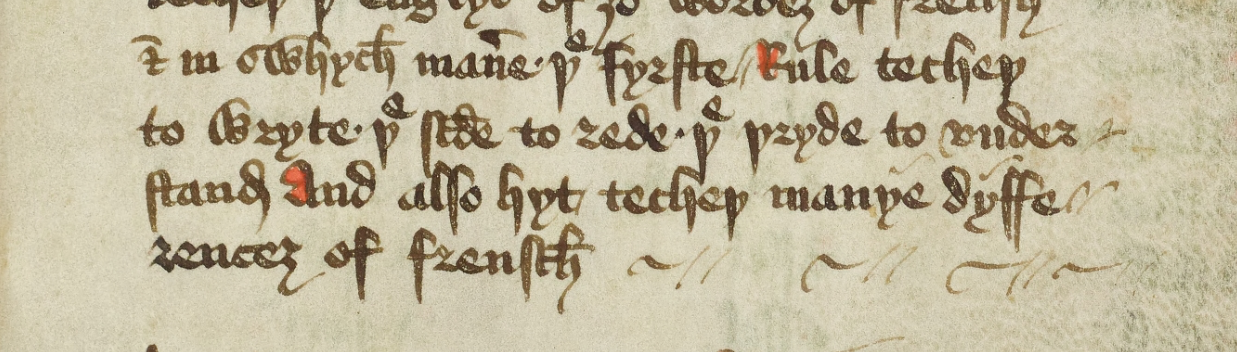

Feature image: ‘The first rule techeth to wrtyte, the second to rede, the thryde to understand; and also hit techeth many dyfferencez of Frensche.’ Cambridge, Trinity College, Wren Library, MS B.14.39-40, fol. 139r