The Centre for Magic and Esotericism

The Centre for Magic and Esotericism

Posted by thjs201

18 October 2024Dr Anna Milon, former PhD student at the University of Exeter and now postdoctoral researcher at Nottingham Trent University, shares her research into Lincolnshire folklore and an infamous witchcraft case.

It has now been about a year since I finished my doctoral studies at Exeter, missing, frustratingly, the launch of the new Magic program. It is only fair, then, that I share what I’ve been up to since: I’ve been fortunate enough to join the AHRC-funded Lincolnshire Folk Tales project headed by Dr Rory Waterman at Nottingham Trent University. Lincolnshire Folklore languishes in obscurity, overshadowed by touristy Yorkshire to the North and more populous East Anglia to the South. But its tales and traditions are no less fascinating, and that is what the project aims to showcase.

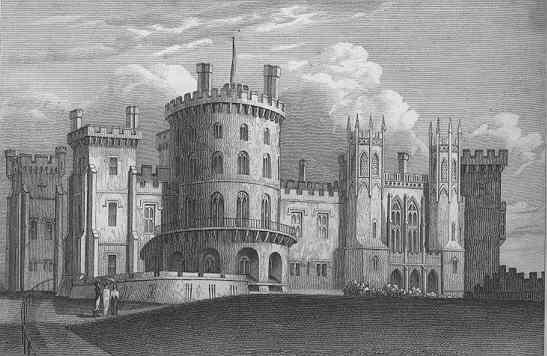

To help the curious orientate themselves, the project website has a map on which various Lincolnshire folk tales are tied to locations where they were collected or where their events unfolded. One entry that made it onto the map is that of the Witches of Belvoir. Despite Belvoir Castle, which gives them their moniker, now being in Leicestershire due to the movement of county borders, their tale is firmly a Lincolnshire one. These three women – mother Joan and daughters Margaret and Phillip (also recorded as Philippa or Phillis) Flower – served in the employ of Francis Manners, 6th Earl of Rutland, and were accused of causing the illness and death through malefic means of his two sons. On this charge, Margaret and Phillip were executed in Lincoln on 11th March 1618/19. Their mother would have likely joined them had she not died on the way to Lincoln Gaol. Owing to the Earl of Rutland’s eminent status and his being left without heirs after the deaths of his two sons, the case ‘deals with one of the most high-ranking victims of witchcraft of his era.’ It is recorded in the pamphlet The Wonderful Discovery of the Witchcrafts of Margaret and Phillip Flower and the ballad The Damnable Practices of Three Lincoln-shire Witches. The atmosphere around the accused is powerfully evoked by Tracy Borman in Witchcraft: A Tale of Scandal, Sorcery and Seduction (2013), and the pamphlet is transcribed and discussed by Marion Gibson in Early Modern Witches: Witchcraft Cases in Contemporary Writing (2000).

But what makes the Witches of Belvoir’s story a folk tale? Putting the reality of witchcraft aside, arguably the key detail of the accused’s ordeal is mother Joan’s death, which has been mythologised through the years. Joan Flower died at Ancaster on the way from Belvoir to Lincoln, about halfway between the two, where the wagon transporting her and her daughters stopped for the night. The contemporary pamphlet reports that Mother Flower

called for Bread and Butter, and wished it might never goe through her if she were guilty of that whereupon shee was examined; so mumbling it in her mouth, never spake more wordes after, but fell downe and dyed as shee was carryed to Lincolne Goale, with a horrible excruciation of soule and body, and was buried at Ancaster.

Allegedly, the woman called for the bread she ate to choke her if she were guilty of witchcraft, and then did promptly choke to death. The circumstances around her demise, if they were based on any actual event in the first place, have been amplified to conform with the popular imaginary of witches being unable to take communion or utter the names of God and his saints. Whatever the true cause of Joan Flower’s death, the story needed to confirm her being a witch even when her conviction in Lincoln could not. Later accounts, no longer invested in cementing her guilt, are still interested in securing Joan’s reputation as a witch. Trowsdale, writing in the 19th century for visitors to Lincolnshire, elaborates on the belief around bread:

Joan Flower, before her conviction, called for bread and butter, and solemnly wished that it might choke her if she was guilty of the crime of which she was accused. This, we would here observe, was one of the tests generally applied in former times to persons charged with witchcraft. It was alleged that anyone who had entered into a compact with the fiends, lost, from the date upon which they bartered their souls in return for their initiation into the art and rites of witchery, the power of swallowing bread with freedom. This belief was grounded upon the supposition that bread, having been consecrated, and being one of the articles of the sacrament, could not be retained in the body of an agent of the evil one.

While Trowsdale only offers a connection between Joan’s asking for bread and butter and consecrated bread being unpalatable for witches, two centuries on the two details have merged. Jacob Hartwell, writing for the Belvoir Blog (run for the benefit of the Belvoir Castle, now hotel and wedding venue) in 2023, describes the episode as follows:

The trial took a sinister turn when Joan Flower, who had initially proclaimed her innocence, died suddenly on the way to the prison at Lincoln. She requested bread as a substitute for the Eucharist (the body of Christ), arguing that something blessed could not be consumed by a witch, and choked after the first bite.

Neither the bread’s consecration nor Joan’s argument that witches could not receive the Eucharist are mentioned in the original pamphlet nor the accompanying ballad. In both texts, Joan calls for bread and butter, surely an unorthodox addition to God’s body. But the particulars of the records of Joan’s death – however far they themselves are removed from the truth – are not as appealing as the myth where a witch contends with an incarnation of the divine. As the Flower women recede further back into history, lacking grave markers or monuments, their legend persists, hoary with ever more fanciful details.

While researching the Witches of Belvoir, I noticed another potential Lincolnshire connection to famous witchcraft trials. Thomas Heywood, co-author of The Late Lancashire Witches (1634), may have been from Lincolnshire. The sensitive treatment of the witch-characters in the play, based on the Lancashire women awaiting trial in London on charges of witchcraft, made me wonder whether Heywood was moved to it by the earlier trial of the Flowers. Heywood collaborated on the play later in life, and may have been in his 40s during the Belvoir trial. However, the scarcity of surviving documents about his life make the claim impossible to ascertain. Even if Heywood was a Lincolnshire man (which is a matter of some debate), he was unlikely to have been in the county during the Belvoir trial, as he is recorded performing at queen Anne of Denmark’s funeral in May of 1619.

Katharine Lee Bates’ diligent research in “A Conjecture as to Thomas Heywood’s Family” (1913) yields two lots of Lincolnshire Heywoods: one family based in Kelstern, north of Lincoln, and one in Little Carlton, near Louth in the east of the county. But neither is a convenient fit, with parish records absent to verify the birth of any Thomas Heywood. On the note of parish records, Bates laments that the church books containing them, ‘many of them still in the form of parchment rolls thrust away in vestry chest or vicarage closet – where I saw one inviting its own destruction by keeping company with the cheese – are not always to be had.’ Thus, we are unlikely to ever know whether Thomas Heywood had any knowledge of the Witches of Belvoir or any sympathy to their plight. Unless, of course, some discerning mouse will forgo the church books and cheese in favour of the bread and butter that choked a witch.