The Centre for Magic and Esotericism

The Centre for Magic and Esotericism

Posted by vk290

3 February 2026This post is part of the ongoing series for the blog Sitting Down with the Magic Centre. You can find all previous posts on the attached link. If you or someone you know is in the Magic Centre and would like to share your research in this way, please message Vic Kendall Weiss at vk290@exeter.ac.uk!

Recently, I sat down with cup of tea in hand to talk to Edith Stewart (she/her), a first-year MA student pursuing the Magic and Occult Sciences program, to talk all things worms, death, belief and the strange places where magic shows up in everyday life.

After completing her BA in History at Jesus College, Cambridge (which she tells me also happens to be one of the filming locations for the upcoming adaptation of H is for Hawk) Edith came to join the Magic Centre in Exeter, continuing her studies through the Masters program and furthering her love for the wild and weird parts of the subject.

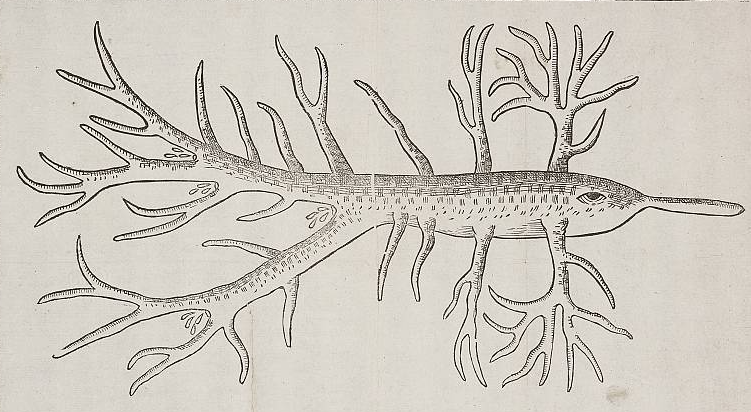

She tells me how her research interests at this point are still evolving, but currently focuses on Early Modern memento mori thought — particularly through the role of the worm. Yes, the worm. Specifically, what worms can tell us about how people in the early modern period thought about death, decay and the inevitability of the body’s end. Edith is refreshingly honest about the fact that she’s still figuring out exactly where this research is headed, which feels appropriate for a project concerned with uncertainty, mortality and things that are naturally wriggly.

What draws Edith to magic is less about grand historical narratives and more about human experience — how people actually live with ideas of death, the divine and the esoteric. She admits that this perspective can “sound dicky” or pretentious, but her interest is grounded in realism: what magic looks like in practice, how belief shapes people and how the same ideas can be both beautiful and dangerous. Magic, for Edith, isn’t just spectacle: it’s something that forms ideologies, identities and ways of understanding the world.

When I asked Edith about her first experience of feeling something magical, she reflected on how hard that question is to answer when childhood blurs the lines between reality and belief so well. Following this logic, she wonders if the tooth fairy would count, or perhaps the time someone gave her a packet of glitter and told her it could make her fly. The latter was strangely an experience we happened to share.

“It’s not normal!” she laughs. “It probably looked like a sort of perverse drug deal!”

Jokes aside, her point was sincere: magic often exists in belief itself — in what people accept as possible, meaningful or real.

When I asked Edith what advice she’d give new MA Magic students, or those wanting to pursue research of the esoteric kind, there was a brief misunderstanding about whether I meant advice or device.

“I don’t know,” she said. “A sword?”

After thinking about it more, she landed on a poignant idea: find something you’re not just interested in, but something that makes you feel something. Everyone has that thing, she believes — though sometimes you have to look a little harder to find it.

I asked Edith about her favourite memory made so far on the MA and soon she rightfully brought up the Tintagel trip (one that I also went on the year before, featured on The Legend of King Arthur History Module) which she described as especially meaningful. Being in a place so tied to Arthurian legend allowed her to see how myth continues to live through tourism, storytelling and cultural reception. She, like me and I’m sure others too, is frustrated now that the trip has lost it’s funding from the University for future years, precisely because the lived, embodied experience of visiting this site felt essential to her studies— not just reading about legend, but seeing how it moves through society in real time. In many ways, she said, that relationship between legend and lived experience is what drew her to magic in the first place.

Edith and her sister enjoying the wild and beautiful landscape surrounding Tintagel Castle

At this point, I asked Edith to imagine herself over a crystal ball, enquiring with it where she might end up in 5 years time both in her research and in her future career. Her response, quite frankly, was one of my favourite of this series so far.

Ideally, she would be rich from using this imagined, highly accurate crystal ball for others. If not, she hopes to be living in the countryside with all the worms.

If you’d like to hear more about Edith’s work, she’s happy to chat and can be contacted at ers235@exeter.ac.uk.