Posted by e.m.vine@exeter.ac.uk

6 February 2024Emily Vine

What’s in an early modern will? On the one hand the answer to this question is straightforward – according to the legal definition a will is the documentary instrument by which a person regulates the rights of others to their property or family after their death. Yet their value as historical records is much broader than this might suggest. The key aim of our project is to use wills to analyse the ‘meaning’ of material culture, and how people’s relationships to material culture changed over time. Read on to find out more about the nature of wills and why they are peculiarly well suited to exploring this theme.

The content of wills

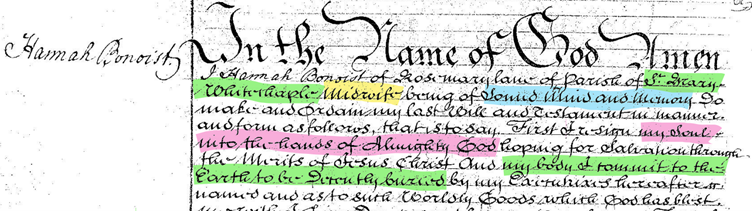

Early modern wills generally followed a formulaic structure which set out an individual’s intentions for the dispersal of their estate and possessions. The example above, the will of Hannah Bonoist, a midwife whose will was proved in 1759, is an excellent example of these generic features.[1] Wills began by naming the individual, identifying where they lived (e.g. ‘The Parish of St Mary Whitechaple’) and offering details of their status or occupation, such as ‘widow’, ‘mariner’, or ‘midwife’. Often they would contain a statement which confirmed their state of health and mind: that they were sick in body, but ‘sound’ enough of mind and reason to make and understand the content of their will. Occasionally individuals were reported as being in perfect bodily health, but mindful that death was inevitable but the timing uncertain. The next phrase would generally be religious in nature, commending their soul to God, and setting out directions for the burial of their body, often identifying a preferred parish churchyard.

Wills often then named an executor or executrix, who may have been the testator’s spouse, adult child, or friend, and who would be tasked with ensuring that the directions made in the will were carried out. Hannah Bonoist appointed her two adult daughters, Mary and Sarah, as ‘joint executrixes’ of her will. The main body of the will would then follow, listing the bequests of money, land, property, farm animals, and personal and household objects that were to be divided up amongst family and kin. Often the will would begin with the largest or most significant bequests of land or money, or those left to ‘closest’ relatives, and subsequently list smaller sums or items, occasionally to increasingly distant kin. Sometimes these itemised lists of bequests would take up less than a page, and other times stretch to seven, eight, or more sheets of paper.

The meaning of wills

So where does ‘meaning’ come into this? For some wills, such as those that comprise little further detail beyond itemised sums of money, it can be difficult, on first glance, to see how we can gauge the meaning of such bequests. But there are several ways that we can ascertain what objects or bequests might have meant, and how they could encapsulate the relationship between testator and beneficiary. Even fairly standard bequests, such as the division of money or an estate between surviving children, were often presented alongside conditions or directions that provide further explanation about life stage or relationships. It was common to state that an individual could not inherit until they had reached a certain age e.g. ‘the age of xxj yeres’. Some parents left different amounts for their married daughters than for their unmarried daughters, or specified that sums would only be received once they got married. Other people left bequests which were dependent on which child, or niece, or nephew, lived the longest. Occasionally bequests were rooted in the assumption that a beneficiary would enter certain careers, for example, ministerial training, or sought to shape how they would make a living. One will, made in 1538, left ‘the occupacion of my ffarme with all my Catell ther to the Use and profite of my Children’.2 Bequests of farmland and farm animals appear to have been common, particularly in the sixteenth century – distributing an individual’s most valuable assets, but also providing the means for surviving relatives to continue to make their living.

With bequests of objects and references to material culture – the focus of our study – there are many more ways to ascertain meaning or the personal value that certain items held. Discussions of objects often used adjectives which provide an insight into the appearance, materiality, use, or household location of an item. Hannah Bonoist left to her daughter Mary ‘a looking Glass in a black frame in the Kitchen’ and ‘my Gold Wedding ring’. Looking glasses would still have been fairly fashionable household items at the time when Bonoist made her will, and the description suggests that this was a substantial and fixed mirror, perhaps wall-mounted. This account suggests that the looking glass was prized more than Bonoist’s other household furniture, perhaps because it denoted a degree of status, or demonstrated her engagement in forms of fashionable consumption. The gold wedding ring was of both financial and emotional value: Bonoist’s husband, who was not mentioned in this will, was presumably dead.

Other descriptions of objects in wills hinted at how the owner ranked or determined value, using phrases such as ‘my best…’ or ‘a new…’: this is perhaps most famously encapsulated by Shakespeare’s will, and his bequest of his ‘second best bed’. In a similar manner, Bonoist left her daughter Mary ‘my best Mantle’ (a type of cloak or gown) alongside ‘half my Linnen and Wearing apparel’. The other half was left to her daughter Sarah, while a Mrs Ann Brown was appointed to divide the linen between the two daughters ‘in an impartial manner’. Her daughters were named executrixes of the estate, but they were seemingly not trusted to equally and fairly share out the inherited wearing apparel between them. Sarah did not get the ‘best mantle’, but she did get ‘the Rest and Residue of my Estate and Effects’. It is notable which items were singled out and described, and which were grouped together under ‘wearing apparel’ or ‘Effects’. The singling out of specific items, with clear directions for their dispersal, provides an indication of the possessions that may have been most treasured by the testator.

Bonoist’s will is a fairly short example: beyond her goods, meticulously divided between her daughters, she left only one further bequest, a single shilling to her husband’s son from his first marriage. Yet even from just three sets of bequests we can gauge a lot about the meaning of Bonoist’s possessions – her best mantle, her gold wedding ring, and her looking glass with its black frame, and about her relationship with her two adult daughters, her step-son, and her trusted friend Ann Brown. We also get an insight into the life and circumstances of a comfortable middling working woman, a widow and a midwife, who had once perhaps engaged in fashionable consumption practices and owned a handful of treasured possessions (the mantle, the looking glass) but ostensibly did not have a large amount of money to leave. Most significantly, the will gives an insight into the living circumstances and relationships of a woman who has otherwise left little trace in the historical record.

The Material Culture of Wills project

Our project seeks to analyse the wills of 25,000 individuals like Hannah Bonoist who died in England between c.1540 and 1790. In each will, the objects bequeathed and described tell a story. In our blog posts that follow over the coming months, particularly our ‘Will of the month’ blog, we’ll be exploring some of these wills in much greater detail. We hope to explore the wide range of lives captured by these documents, and to reveal the insights that wills provide into their living circumstances, possessions, and what certain objects may have meant to each testator.

[1] The National Archives PROB 11/850/326 Will of Hannah Bonoist, Midwife of Saint Mary Whitechaple, Middlesex, 19 November 1759.

The National Archives PROB 11/850/326 Will of Hannah Bonoist, Midwife of Saint Mary Whitechaple, Middlesex, 19 November 1759.

Hannah Bonoist

In the Name of God Amen

I Hannah Bonoist of Rosemary lane of parish of St Mary

Whitechaple Midwife being of Sound Mind and Memory Do

make and Ordain my last will and Testament in manner

and form as follows, that is to say. First I resign my Soul

into the hands of Almighty God hoping for Salvation through

the Merits of Jesus Christ And my body I commit to the

Earth to be Decently buried by my Executrixes hereafter

named and as to such Worldly Goods which God has blest

me with I Give Devise and bequeath as follows First I

Give to William Bonoist my husbands Son by his first wife

One Shilling Also to my Daughter Mary Patterson a looking

Glass in a black frame in the kitchen my Gold Wedding ring

my best Mantle with half my Linnen and Wearing apparel

besides the Sundry Goods of hers in my house which I Gave

her in my life time Also I Give to my Daughter Sarah Reay

the other half of my said Linnen and Wearing apparel

with all the Rest and Residue of my Estate and Effects

whatever and it is my Desire that Mrs Ann Brown of Old

Gravel lane St Johns Wapping do Divide my said Linnen

and Wearing Apparel between my said Daughters Mary

Paterson and Sarah Reay in an Impartial manner and I

hereby appoint my said Daughters Joint Executrixes of this

my Will which revoking all other and former Wills by me

heretofore made I Declare to be my last in the Presence of

Christopher ffisher and Joseph Ray this 29 Day of November

And in the year of our Lord One thousand seven hundred and

ffifty Eight, the Mark of Hannah Bonoist, Witness Christopher

Fischer, Jos. Reay

This Will was proved at London the nineteenth

Day of November In the year of our Lord One Thousand Seven

Hundred and ffifty nine before the Worshipfull George Scarris

Doctor of Laws surrogate of the Right Worshipfull Edward

Simpson also Doctor of Laws Master Keeper or Commissary

of the prerogative Court of Canterbury lawfully constituted

by the Oaths of Mary Patterson (Wife of Robert Patterson)

and Saray Ray (Wife of William Ray) the Executrixes

named in the said Will to whom administration was

Granted of all and Singular the Goods Chattels and

Credits of the deceased having been first sworn only to administer