Posted by Laura Sangha

25 March 2024We are currently re-advertising our funded PhD studentship Global Commodities in Early Modern Wills. The focus of the studentship is intended to be broad and elastic so that the successful student can shape it as they wish, but we thought it would be helpful for potential applicants if we provided more detail about the potential of global commodities in wills as a focus of historical study. In this post we offer various suggestions of themes that could be adapted according to a candidate’s own research interests – this is not a list of what should be covered, but rather some suggestions of various directions the studentship could be taken in. We also say a bit about how the studentship fits into our Leverhulme-funded project ‘The Material Culture of Wills, England 1540-1790’.

Who are we looking for?

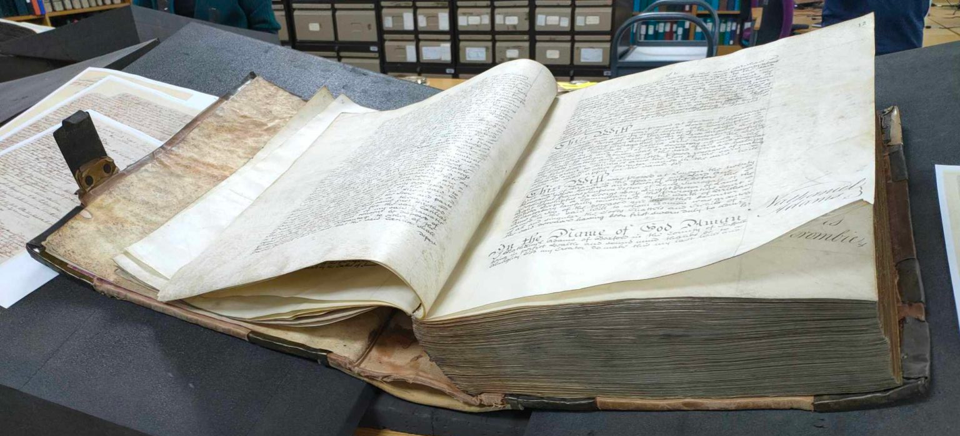

This fully-funded studentship (UK student fees + maintenance grant) is suitable for a student with an interest in late medieval and/or early modern social history or economic history: there is no need to have studied global commodities before. Perhaps you have an interest in maritime history, trade, material culture, or wills. The PhD will make use of the 25,000 wills from the Prerogative Court of Canterbury (PCC) that cover the period 1540-1790 and are being transcribed by the project: the transcriptions and a database of objects mentioned will be made available to the student. Beyond that, the topic can be interpreted flexibly – it is helpful to think of it under three headings: material culture, global goods, and commodities and trade – which are outlined below. There are also other themes that could be explored including gender, status, occupation, rural/urban differences, transnational communities: we’ve given a bit more information about these too. While there is a growing literature on global commodities in early modern England (some suggested reading is provided at the end of the blog), this large sample of wills offers a fresh perspective with great potential for important new research making a substantial contribution to the history of this period.

Material culture

The project focuses on the goods and monetary wealth that were bequeathed in wills. While documents such as probate inventories provide more comprehensive lists of people’s belongings, wills have the advantage of indicating how people felt about their possessions. They show that objects were significant enough to be singled out, described in detail, and bequeathed to a particular person, rather than forming part of ‘all my other goods’ that the executor dealt with. A central aim of the project is to examine attitudes towards goods, and how this changed over time, under the influence of factors such as increased quantities of imported goods, more sophisticated banking and financial devices, and changing attitudes towards wealth. There is also scope to research some types of objects in detail – for example, examining surviving items in museum collections and drawing connections to how they were described in wills. How were these new types of objects incorporated into English culture?

Global goods

Global goods were those imported from outside Europe. In this period non-European goods found in English wills include Indian silks, painted cloths and calico; Chinese porcelain; tropical hardwoods such as mahogany; and quantities of tobacco and sugar found in some colonial wills. We also encounter British and European objects that were designed for the consumption of non-European products, such as items related to tea-consumption or silver forks for eating preserved ginger. Normally it is quite hard to find these relatively rarely mentioned items in a collection of wills, however the project is creating a database identifying the bequests in 25,000 wills, allowing the PhD student to focus in on those wills which do mention these types of goods and examine the contexts in which they were bequeathed. There is scope to compare these objects with European imports and British goods. What do wills tell us about the impact of global goods on English society?

Commodities and trade

Wills rarely mention explicitly where goods come from, but we can infer that they were traded by using other sources to infer their geographical origins. The occupations of testators also reveal individuals who were directly involved in trade and retail, for instance master of ships, mariners, merchants and various types of retailers. It would be interesting to know if these people made more bequests of global goods than others. The PCC collection also includes wills made by people who were not resident in England but owned property there: these include, for example, plantation owners in the Caribbean and merchants in India. These wills could provide another focus of research. What do wills reveal about the methods by which global goods became English possessions?

Other themes

The focus on global commodities does not preclude using the wills to explore other themes through this lens – are there gendered differences in the bequests of global goods, for instance, and how do bequests of this type vary according to the social status, occupation or place of residence of the will-maker? How did the wills made by those resident abroad differ from wills made by English residents? Or did individuals with different personal characteristics (whether place of origin, gender, class, etc) attribute different meanings to a given object – did a mariner who interacted with non-European goods on a daily basis have a different relationship to such objects compared to a person who rarely, if ever, left England and Wales?

Benefits of being part of a larger project

The student will also benefit from the support and expertise of the project team (including a second doctoral student) and they would be invited to join project meetings, workshops and other activities. This will equip them with knowledge of cutting-edge Digital Humanities methods and familiarise them with crowdsourcing research methods. The student will have the opportunity of a six-week placement with the project partner, the National Archives. These insights, opportunities and skills will complement and extend their doctoral research.

Click here for details of how to apply.

Jennifer L. Anderson, Mahogany: The Costs of Luxury in Early America (Cambridge MA, 2012).

Troy O. Bickham, ‘Eating the Empire: Intersections of Food, Cookery and Imperialism in Eighteenth-Century Britain’, Past & Present, 198 (2008), 71-109.

Paula Findlen ed., Early Modern Things: Objects and Their Histories, 1500-1800 (Routledge, 2013).

Robert Finlay, The Pilgrim Art: Cultures of Porcelain in World History (University of California Press, 2010).

Anne Gerritsen and Giorgio Riello ed., Writing Material Culture History (Bloomsbury, 2015).

Amitav Ghosh, The Nutmeg’s Curse: Parables for a Planet in Crisis (Chicago, 2021).

Tara Hamling and Catherine Richardson eds., Everyday Objects: Medieval and Early Modern Material Culture and its Meanings (Ashgate, 2010).

Daniel Miller, Stuff, (Polity, 2010).