Posted by Laura Sangha

7 May 2024Laura Sangha

It’s safe to say that the Wills Project wouldn’t be possible without drawing on the skills and knowledge of a wide variety of volunteer ‘citizens’ – or rather, if we were to attempt our project alone it would take decades, rather than the four years that we have funding for. People power fuels our research in two ways: a small team of expert volunteers are helping us to train a bespoke Handwritten Text Recognition (HTR) model, and later a much bigger pool of participants will check and correct the 25,000 transcriptions of early modern wills that the HTR produces.

As a matter of fact the Wills Project is just the latest in a quite long line of projects that see researchers working alongside volunteers from the public to conduct historical investigation, a practice that has become known as ‘citizen science’ or ‘citizen humanities’. Since this is such an important part of our methodology, throughout the life of the project I plan to write a series of related posts reflecting on this way of working. In this first piece I introduce the practice of ‘citizen humanities’ and consider the untapped potential and creativity that digitally enabled citizen participation can unlock.

Citizen Humanities: nothing new

Although the term ‘citizen humanities’ was only coined in the 2010s, collaboration between citizens and researchers to produce something that benefits both is increasingly common. In fact, you probably won’t be surprised to learn that the practice also has a long tradition.

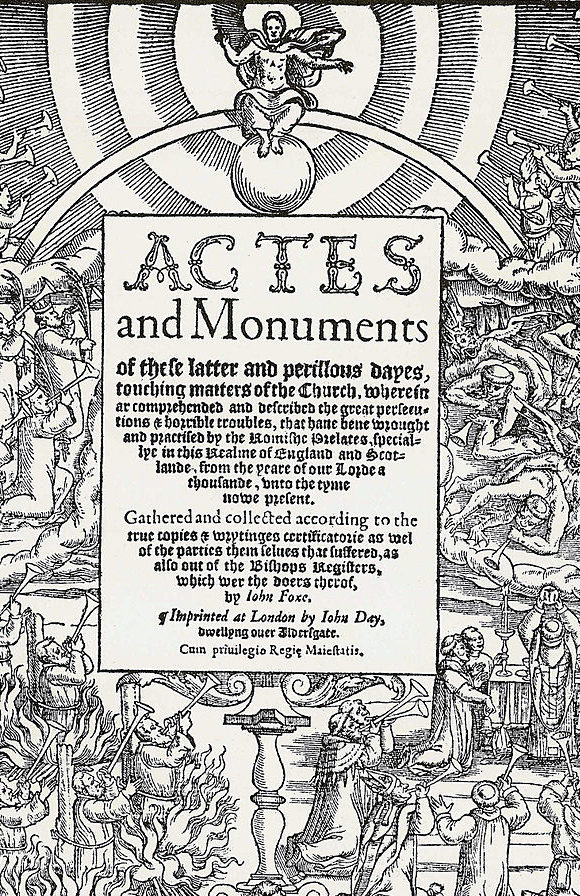

Off the top of my head I can think of a number of early modern ‘projects’ in my own field that fit the bill. For instance, parts of John Foxe’s Elizabethan history of the English Reformation, Actes and Monuments, were written by the very people who were to be its readers, since Foxe learned of the existence of many of the Tudor protestant martyrs he described in his book from accounts sent to him by eyewitnesses to their executions. Indeed, the author sat at the centre of a network of godly clergymen, antiquarians and merchants who plied him with the data that filled the pages of his book, and some passages are copied verbatim from correspondence he received.

In seventeenth-century Europe, natural philosophy (the field of activity that evolved into what we now call ‘science’) was studied not in universities but by ‘amateur’ and self-funded researchers like Francis Bacon, Margaret Cavendish and Thomas Browne. From 1660 The Royal Society gathered information about the natural world from its members by correspondence which it published in its journal Philosophical Transactions. What’s more, Deborah Harkness has shown that many ‘scientific’ publications drew on the expertise of a much wider assortment of Elizabethan citizens: merchants, gardeners, midwives, barber-surgeons, engineers and alchemists who experimented, invented and shared their resulting knowledge with more socially elite practitioners. The latter were the ones who eventually wrote up this data in their own published works, a process that sadly tended to erase the contributions of the citizens.

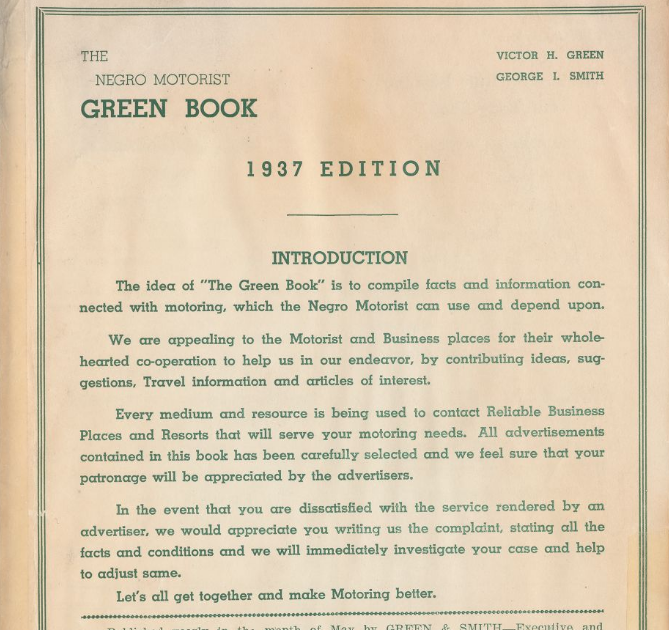

Jumping forward in time, some of the more famous examples of collaborative humanities projects would include the compilation of the Oxford English Dictionary, which used volunteers to identify unlisted words in old books and manuscripts. The concept could stretch to include The Green Book, the travel guide by Victor Hugo Green containing material from readers and U.S. Postal Workers on places that were safe and hospitable for African American travellers in the Jim Crow era, and we should certainly acknowledge Wikipedia, the place where I first encountered this information.

Citizen Humanities: Redux

Private engagement with research didn’t end with the professionalisation of science and humanities subjects, but rather has run parallel to and been entangled with work within the academy. However in recent years the potential of public participation in research has been transformed by the coming of the internet, which allows much larger groups of dispersed participants to work collaboratively, and much more quickly than the older technology of written correspondence.

The Wills Project also has the advantage that it combines this digitally-enabled participation with machine learning to create a human-computation infrastructure that enhances the capacities of both. Unlike existing studies of wills that draw on a few thousand examples, we will thus be able to extract data from 25,000 documents and to track patterns in bequests and objects across three centuries.

So why can’t the machine just do it?

In the last few years, machine learning has advanced to such an extent that some citizen humanities tasks (like tagging or transcribing) might become obsolete. However, involving ‘citizens’ to gather and process information doesn’t just have the benefit of allowing us to do research at scale, there are myriad other reasons for adopting such a methodology that would be lost if we handed it all to the machine. To do justice to these benefits I will need another post, but I’ve summarised some of the key ones below – in future posts I hope to explore best practice in working with ‘the crowd’ and the challenges and ethics of utilising citizens in this way.

In conclusion, contributions of volunteers have always played a vital part in preserving, understanding and making cultural heritage accessible, and we hope that the Wills Project will continue to allow citizens to be involved research in similar ways.

Citizen Humanities

Open access co-edited collection: The Science of Citizen Science (Springer Cham, 2021) – especially the chapter by Heinisch et al. on Citizen Humanities.

Crowdsourcing project news from the British Library.

Paper Trails: The Social Life of Archives and Collections (UCL Press, Books as Open Online Content). An open access BOOC which publishes practitioners’ reflections on ‘Co-Production’ and ‘Engagement’ in their own research.

History

John Foxe: the excellent online edition of Actes and Monuments hosts a number of interpretive essays on its Critical Apparatus tab, including this Brett Usher piece on key contributors to the work.

Deborah E. Harkness: The Jewel House: Elizabethan London and the Scientific Revolution (Yale, 2008). On the broad based nature of ‘scientific’ activity in the capital.

Simon Winchester, The Surgeon of Crowthorne: A Tale of Murder, Madness and the Love of Words (1998). A history of the making of the OED focused on one of its most prolific contributors, William Chester Minor.

The Negro Motorist Green Book: Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service. Includes an online exhibition and information for citizens about how they can share their own stories to chronicle the oral history of the Green Book.