Posted by e.m.vine@exeter.ac.uk

27 June 2024In this month’s post, one of our Expert Volunteers shares her research into one of the wills she came across when transcribing pages for our project.

Liz Wood, archivist and project volunteer

There is a formula, a routine, to official copies of probate records. The same impersonal clerical hand, standard phrases about mind, bodily health and God, and then a legalistic division of material wealth which distils decades of personal relationships, tensions and love to ‘I devise and bequeath to […]’. Stories, of course, still show through the legal straitjacket and, with a bit of digging, the 1724/5 will of Mary Andrews takes us from the beaches of Margate to the Baltic strait, touching on Britain’s Empire-building and boom-bust economic revolution along the way.[1]

The will itself gives us the bones of the story. In 1724 Mary Andrews of Wapping, widow, ‘considering the great Uncertaintyes of this transitory life and for the avoiding of Controversies after my decease’, made her will. Her personal estate was split between her three daughters, two grandchildren and mother. Andrews’ legatees received a ‘Silver Tankard marked R : M and A’, the rest of her ‘Plate and Rings’, part shares in three named ships, and an annuity of £5 generated by ‘One hundred pounds Stock … in the South Sea Company’.

Property ownership was overwhelmingly male during Mary Andrews’ lifetime. Before the Married Women’s Property Act was passed in 1870, women lost their separate legal identity and property rights if they married, with the husband taking control of both. Widowhood gave Andrews ownership again and, like other widows, she used the probate system to pass her goods on. It’s striking that five out of six of her beneficiaries were women. The only male presence in Mary Andrews’ will was a child, her grandson John Horsly.

‘My Silver Tankard marked R : M and A’

Bennett Andrews, recipient of the most obviously personal legacy in her mother’s will, was also a key to identifying the family’s Kentish background. The unusually named Bennett was baptised in St John in Thanet (Margate) on 6 March 1697/8, the daughter of Richard Andrews (Mary doesn’t get a look-in in the baptism record).[2] Sixteen years earlier, Richard Andrews and Mary Bennett had married in Canterbury on St Valentine’s Day 1681/2. At the time of their marriage, Margate-based Richard Andrews was a seaman, Mary Bennett was from Sandwich, 10 miles down the Kent coast.[3] The couple had at least seven children in Margate, of whom Bennett Andrews was the youngest.

The marks on the tankard, remembered in the will, combine the initials of Mary Andrews and her husband. A wedding gift, perhaps, or later symbol of their marriage. An example of a betrothal tankard for ‘I P H’, also married in 1682, may give us an idea of how the heirloom looked.

‘Stock which I have in the South Sea Company’

In her will, Mary Andrews included financial provision for her mother (described as ‘mother in law’) Sarah Bennett. Mrs Bennett’s annuity of £5, paid half yearly, was supported not by family lands but by paper wealth – ‘One hundred pounds stock in the South Sea Company’.

The South Sea Company was formed in 1711 and given a monopoly by Parliament on British trade with Spanish colonies in South America. In 1713 Spain transferred their ‘asiento’ (Crown license) to transport and sell enslaved people to its South American colonies from French traders to British, making the South Sea Company the sole ‘legal’ supplier of enslaved people to the Spanish Colonies until 1750.

Mary Andrews wasn’t the first member of her family to invest in the South Sea trade. The 1712 will of her son Richard, a mariner like his father, included a reference to his ‘Capitall Stock of the South Sea Company’.[4] The young man left this, like all his possessions, to his ‘Hon’d Mother Mary Andrews’.

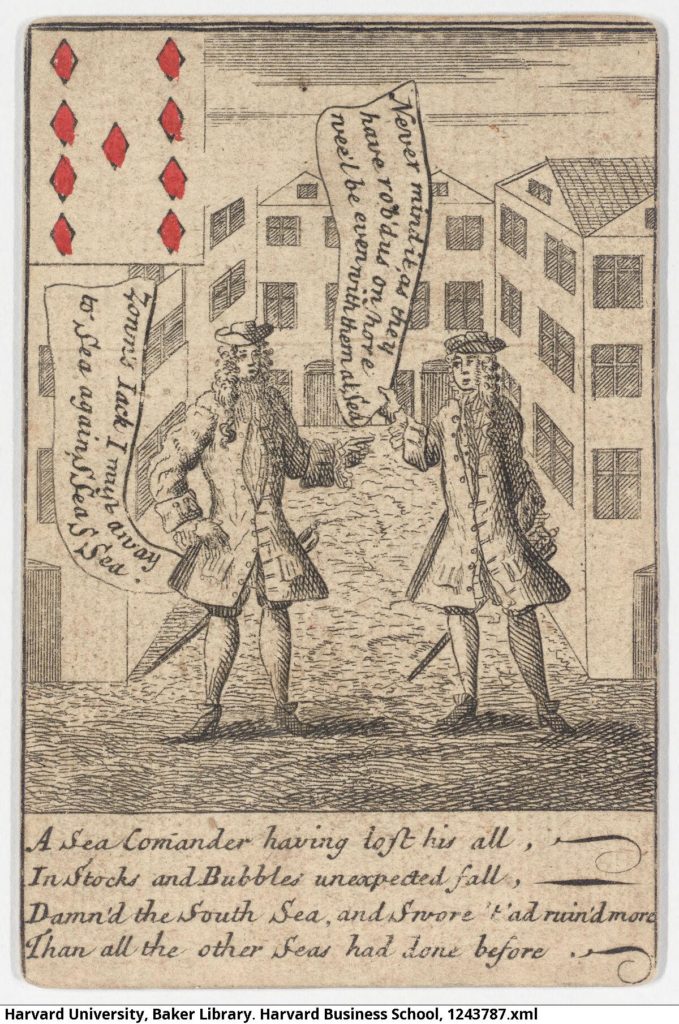

The South Sea Company has been perhaps more notorious for causing the first international stock market crash than for trading human beings. Richard Andrews was an early adopter, buying his shares in 1711 or 1712. By 1720 the Company was at the centre of speculative mania, fuelled by loans to buy overinflated stock that was regarded as safe as the recently established Bank of England. The ‘Bubble’ burst in September 1720, with shares plummeting in value from £950 a piece in July 1720 to £185 in December 1720.[5] The British economy tanked, bankruptcies and suicides rose, the satirical print industry had a field day, and the trade in enslaved people carried on regardless. By 1724, when Mary Andrews linked her mother’s subsistence to the Company’s stocks, the level of return had presumably stabilised.

The brief reference to the South Sea Company in Mary Andrews’ will gives us a glimpse of how the worst of empire was rendered mundane in formal documents. It also gives a clear indication of the changing nature of the British economy from the late seventeenth century onwards – a shift from more tangible property like fields, cows, corn, tools, etc., to pieces of promissory paper.

‘One full and equal two and thirtieth part of the good Ship…’

Three ‘good Ships’ were part-owned by Mary Andrews at the time of her death – the ‘Anne & Mary’, captained by her son-in-law Samuel Moody, and the ‘Merrygold’ and ‘Josiah’, captained by brothers Michael and Edward Hales.[6] In all three cases Andrews had a 1 in 32 share in the vessels. Part-ownership of merchant shipping could be lucrative but came with an inherent risk. The wife and mother of lost sailors would have been only too aware that it would take just one bad storm to sink her investments and leave her daughter widowed.

Early eighteenth-century ‘In-letters’ to the Navy Board, individually described in the National Archives’ catalogue, contain detailed information about Naval dockyard management. All three captains and their ‘good ships’ are mentioned in the correspondence and all three were following the Baltic trade, transporting cargos of hemp and fir timber from Konigsberg (now Kaliningrad), Archangel, Riga and an unnamed port in Norway. One letter shows that even if your ship got safely into port, you weren’t guaranteed a good pay day – on arrival at the Royal Dockyard, Chatham, in 1717 the ‘Josiah’ was ‘found to be falsely packed and containing rotten and decayed hemp’.[7] Hemp and fir were both vital products for Royal Navy shipbuilding, hemp for the ropes and fir for masts and decking.

Sisters of Wapping

It’s likely that Mary Andrews moved from Margate to Wapping between 1698 (the baptism of her daughter Bennett) and 1704 (the marriage of her daughter Anne). By 1712, when her only surviving son wrote his will, she was a widow.

Early eighteenth-century Wapping was a Sailortown, with most inhabitants involved directly with seafaring or with the service industries that surrounded it. Maritime households like Mary Andrews’ were run by women while the men were absent, either through long sea voyages, early death or abandonment.

Old Bailey Proceedings give us glimpses of daily life in Wapping. One victim of Sailortown theft was Mary Andrews’ son-in-law, Captain Samuel Moody, who had ‘5 Gallons of Red Lisbon Wine’ stolen from his ship in 1714.[8] Though Mary Andrews was lucky enough to stay out of court, other women of Wapping were less fortunate. The 1748 case of Elizabeth Tod includes the evidence of five women against one man, a gin-drunk lawyer called Henry Rooke who had beaten Tod to ‘gore’ and stolen her money.[9] At least two of the women had husbands at sea, one expected ‘every day from Jamaica’, the other a ‘Guineaman’ or slave trader, ‘gone these six years, trading on the coast of Guinea’. The court report makes it clear that the propriety of men-less Sailortown women was regarded with suspicion.

In Wapping the wills of dead mariners could be an opportunity to make money. Unscrupulous ship’s clerk Edward Anchors, convicted in 1727, had ‘for some Years … followed the Practice of Counterfeiting Wills, and getting some evil disposed Persons to prove them.’[10] If the deceased was married, Anchors employed ‘a Sister of Wapping’ as the ‘widow’ to trick the probate court.

Making Connections

This blog is the result of a volunteer with an archival background and a bit of idle curiosity spending a weekend poking about in some online databases to explore the context of a single transcribed will. Probate records can be a springboard to research into multiple subjects, from the history of a specific family to the study of major historical events such as the South Sea Bubble. A wealth of online resources are available to support this sort of research – our ‘Resources’ page can provide a great starting point.

In the Name of God Amen

I Mary Andrews of the Parish of St. John of Wapping in the County

of Middlesex Widow being sick and weak of body but of sound and

perfect mind and memory considering the great Uncertaintyes of this

transitory life and for the avoiding of Controversies after my decease do

make publish and declare this my last Will and Testament in manner

and form following that is to say ffirst and principally I recommend

my Soul into the hands of Almighty God my Creator hoping to receive

full pardon and free Remission of all my Sins through the death and

merits of my only Saviour Jesus Christ and my body I commit to the

Earth to be decently buryed at the discretion of my Executrixes hereafter

named and as for and concerning all my worldly Estate as the Lord in

his good Mercy hath lent me my mind will and meaning is that the

same shall be employed and bestowed as followeth Imprimis that all

my just debts and ffuneral Charges be first paid and satisfied Item I

give devise and bequeath unto my Daughter Bennett Andrews my

Silver Tankard marked R : M and A. Item I give devise and bequeath unto

my Daughters Anne Moody the Wife of Samuel Moody and Mary

Horsly the Wife of George Horsly all the rest residue and remainder of my

Plate and Rings to be equally divided between them share and share

alike Item I further give devise and bequeath unto my said Daughter

Bennett Andrews one full and equal two and thirtieth part of the good

Ship called the Merrygold Capt Michael Hales Commander togeather

with one full and equal two and thirtieth part of the Appurtenances

thereunto belonging To hold to her and her Assigns for ever Item I

further give devise and bequeath unto my said Daughter Anne Moody

one full and equal two and thirtieth part of the good Ship called the

Anne and Mary Captn Samuel Moody Commander togeather with one

full and equal two and thirtieth part of the Appurtenances thereunto

belonging To hold to her and her Assigns for ever Item I give devise

and bequeath unto my Grandchildren John and Sarah Horsly one full

and equal two and thirtieth part of the good Ship called the Josiah Capt

Edward Hales Commander togeather with one full and equal two and

thirtyeth part of the Appurtenances thereunto belonging To hold unto

my said Grand Children John and Sarah Horsly their Heirs and Assigns

for ever Item I give devise and bequeath unto my Mother in Law Sarah

Bennett the Sum of ffive pounds per Annum during the Term of her

natural life to be payd half yearly and for the more sure and better

payment of the said money I do hereby charge the Sum of One hundred

pounds Stock which I have in the South Sea Company with the

payment thereof during her life and after her decease the same to be sold

to the best advantage and equally divided amongst my three Daughters

hereafter mentioned share and share alike and Lastly Whereas I have

heretofore advanced unto my said Daughter Anne Moody the Sum of

Eighty pounds in part of what moneys and Effects I designed to give her

at the time of my decease therefore my mind will and meaning is that

the said Sum of Eighty pounds shall be allowed in part of her part of

the Surplus of my Estate hereinafter bequeathed that is to say all and

singular such Sum and Sums of money Bonds Bills Annuityes Stock of

what kind or nature so ever Household Goods Chattles and All other

Estate whatsoever as shall be any ways due owing or belonging unto me

at the time of my decease I do give devise and bequeath the same unto

my said Daughters Anne Moody Mary Horsely and Bennett Andrews to

be equally divided between them share and share alike except as before

excepted And I do hereby nominate and appoint my said Daughters Anne

Moody and Mary Horseley sole Executrixes of this my last Will and

Testament hereby revoaking all former and other Wills Testaments

and Deeds of Gift by me at any time heretofore made and I do ordain

and ratifie these Presents to stand and be as my only last Will and

Testament In Witness whereof I have hereunto set my hand and Seal

the eleventh day of December Anno Dom one thousand seven hundred

and twenty four and in the eleventh year of the reign of our Sovereign

Lord George by the Grace of God King of great Britain &c. Mary

Andrewes. Signed Sealed published and declared by the Testatrix as her last

Will and Testament in the presence of Jno Mercer Jno Newby Attor at Law

Probatum fuit hujusmodi Testamentum apud London undecimo

die Mensis Januarij Anno Domini millesimo septingentesimo vicesimo

quarto coram Venerabili Viro Gulielmo Phipps Legum Doctore

Surrogato Venerabilis et Egregij Viri Johannis Bettesworth Legum

Doctoris Curia Prerogativa Cantuariensis Magistri Custodis sive

Commissarij legitime constituti Juramentis Anna Uxoris Samuelis

Moody et Maria Uxoris Georgij Horsley Executricum in dicto Testamento

nominatarum quibus commissa fuit Administratio omnium et singlorum

bonorum jurium et creditorum dicta defuncta de bene et fideliter

Administrando eadem ad sancta Dei Evangelia jurat Examr

[1] The National Archives; PROB 11/601/75 (https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/D629794). Written on 11 Dec 1724, proved on 11 Jan 1725.

[2] FindMyPast Kent Baptisms, accessed on 22 June 2024.

[3] FindMyPast Kent Marriages and Banns, accessed on 22 June 2024. The couple were both 25 at the time of their marriage.

[4] The National Archives; PROB 11/538/213 (https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/D677841). As Richard Andrews was baptised in Margate in September 1690, he would have been about 23 when he died. The will was written on 5 Nov 1712 and proved 15 months later on 5 Feb 1713/4.

[5] Statistics quoted in ‘The South Sea Bubble, 1720’, online resource from Harvard Library (https://curiosity.lib.harvard.edu/south-sea-bubble/feature/the-crash) accessed on 22 June 2024.

[6] Samuel Moody had married Anne Andrews at St Martin, Ludgate, on 1 October 1704. Both were living in Wapping at the time (Ancestry London Church of England Baptisms, Marriages and Burials, accessed on 23 June 2024). The sibling relationship of Michael and Edward is confirmed in the 1733 will of Michael Hales, mariner (The National Archives; PROB 11/659/151 (https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/D597611)).

[7] The National Archives; ADM 106/709/230 (https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C16726329)

[8] Old Bailey Proceedings Online, April 1714: Trial of John Hopkins and Joseph Green (https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/record/t17140407-40), accessed on 23 June 2024. The receiver of stolen goods, Joseph Green of Wapping, was acquitted after calling “Witnesses to prove that it is customary to buy such parcels of Wine of Sailors”.

[9] Old Bailey Proceedings Online, May 1748: Trial of Henry Rooke (https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/record/t17480526-18), accessed on 23 June 2024.

[10] Old Bailey Proceedings Online, July 1727: Trial of Edward Anchors (https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/record/t17270705-51), accessed on 23 June 2024.