Posted by Laura Sangha

9 July 2024Generously funded by the University of Exeter’s Public Engagement with Research Fund.

Many thanks to the knowledgeable and generous attendees at our two recent workshops (June 2024) at The National Archives and the University of Exeter. Both days were marked by lively conversations and the fruitful exchange of ideas have kindled plenty more flames to feed our project furnace. We were particularly pleased that some of our Expert Volunteers were able to attend – more on them below – and more generally we were greatly fortunate in the wealth of expertise that participants bought to the table. In this post I report what we got up to and reflect on some of the key points of discussion that emerged.

Presentations

The workshops took the form of a mix of talks and discussions about wills as remarkably rich historical resources alongside activities where we processed and analysed some wills themselves. We began by introducing our project, explaining its intellectual origins and the stage we are at in our quest to transcribe 25,000 wills. This was also a means to celebrate the contribution of our 22 Expert Volunteers, the palaeographers who have transcribed hundreds of pages of wills for us that have been used to train our Transkribus Handwritten Text Recognition (HTR) model. Mark Bell, the project’s Technical Expert and Consultant at The National Archives (TNA) explained the complicated process of automating transcription, and reported that the HTR model is performing well when applied to the digital copies of wills in TNA’s collection. As expected, more training will be undertaken to improve its performance further before it is applied to all 25,000 documents.

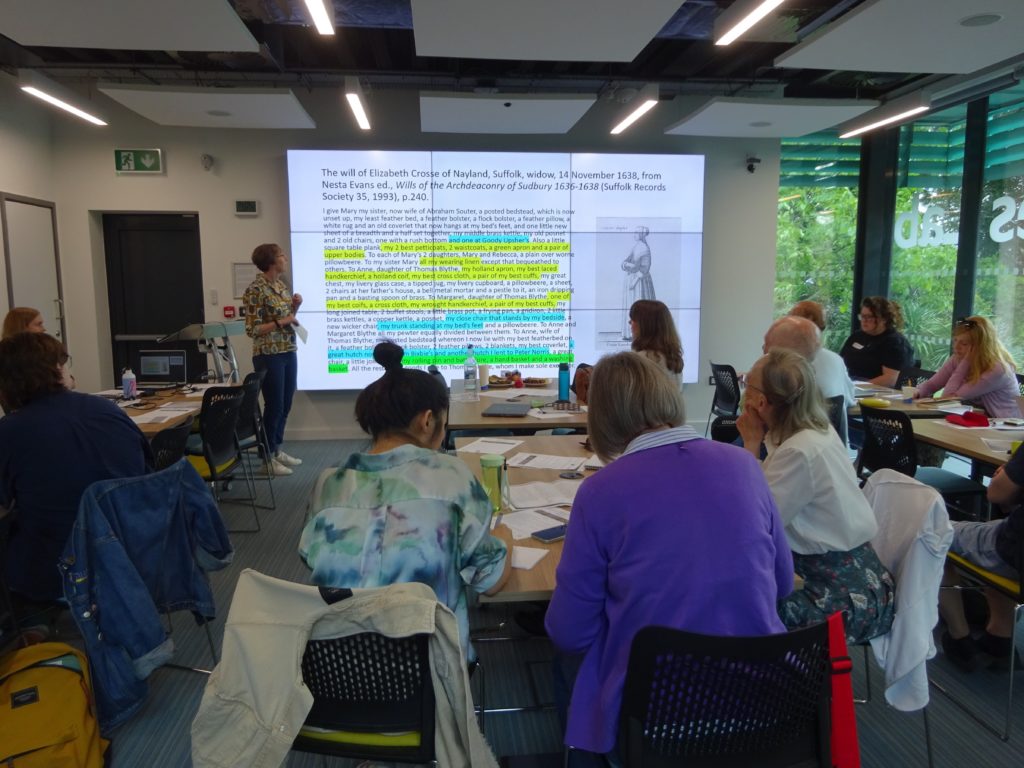

We also outlined the key economic, social and cultural themes that we will be exploring through our data (see our ‘About’ page for more on our method and research questions). Our project leader, Jane Whittle, gave a more detailed talk on household items in early modern wills, in particular the different strategies that were deployed in women’s wills in comparison with those of men. Once our database is complete we will be able to examine Jane’s insight that there were male and female cultures of will making from a variety of different angles across our whole period.

In one of two lightning talks I gave a brief summary of the myriad of historical topics that historians draw on wills to research: biographical or family histories; local case studies; microhistories; studies of occupational hierarchies, consumerism and global trade, and material culture all got a nod. I spent a bit more time on the way that historians in my own field of religious history have exploited wills, since they are one of very few types of source that survive in great numbers which might yield information about belief and confessional identity (for instance through distinctive preambles or bequests for intercessory prayer).

Emily Vine then gave a second speedy overview of the way that testators added conditions and caveats to their wills to cater for ‘the uncertainty of this transitory life’, a reminder too that wills only show us a testator’s intentions, not what actually happened after they died (read Emily’s blog post for more detail).

Activities

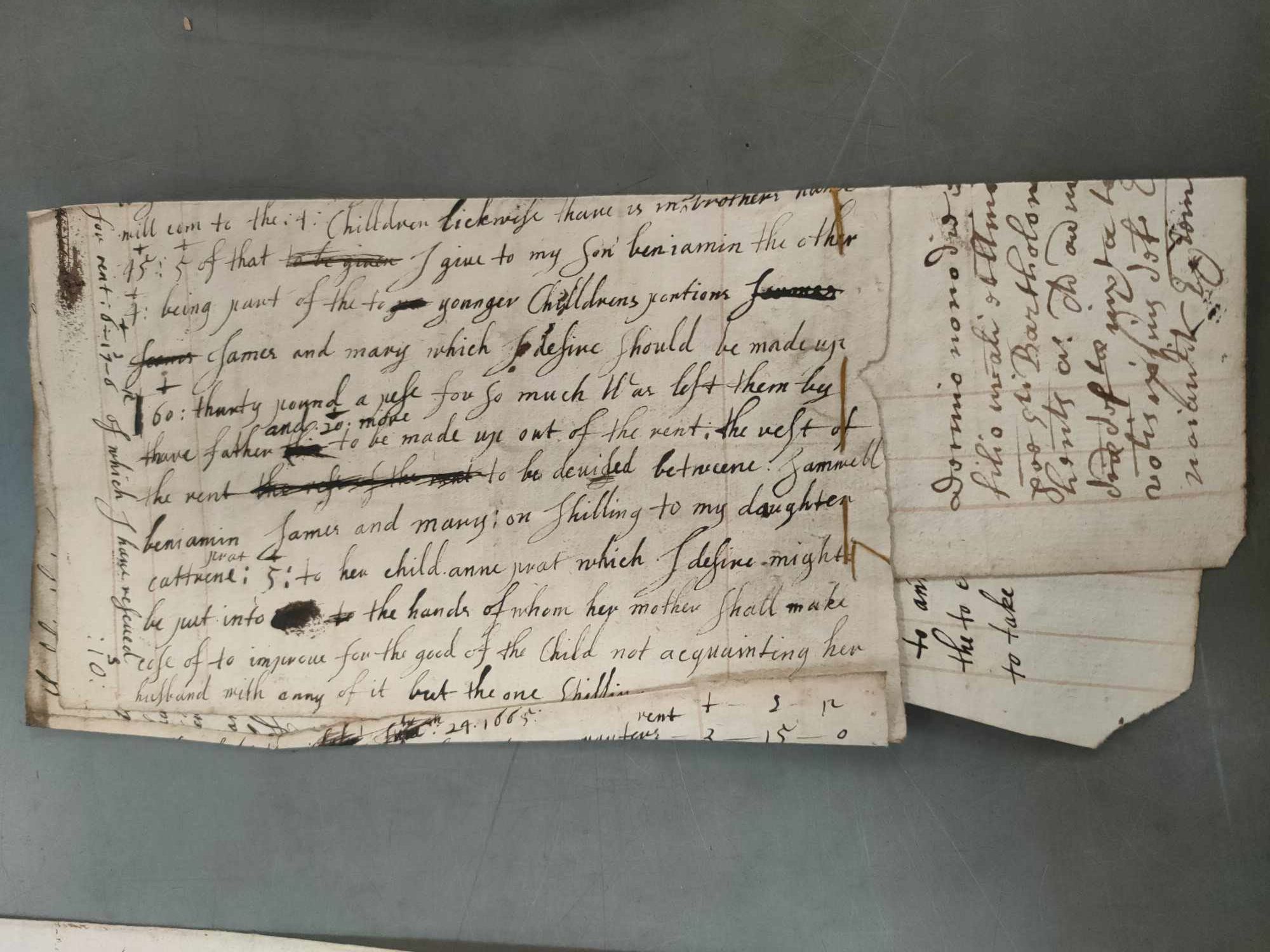

Our first interactive session was designed to consider the materiality of wills as sources. We gave attendees two copies of the same will and invited them to compare them – an exercise that was actually suggested by one of our Expert Volunteers, Judy Lester.

The first version took the form of photos of an original will that Emily had found in TNA series PROB 10: Prerogative Court of Canterbury and Other Probate Jurisdictions: Bundles of Original Wills and Sentences. It was the will of Margaret Nelham of St Bartholomew, London, made in July 1665 and proved in August of the same year. We compared this original with the copy of Margaret’s will in the church court register, part of TNA series PROB 11: the Prerogative Court of Canterbury and related Probate Jurisdictions: Will Registers. It is PROB 11 registered copies of wills that TNA put on microfilm and later digitised, so when you consult a TNA will online it is the PROB 11 copy that you are viewing. Since we are applying our HTR model to the digitised wills, we are producing transcriptions of the registered copies, not the wills themselves.

Our comparison of Margaret’s PROB 10 original will with its PROB 11 registered copy drew attention to the benefits and drawbacks of working with either version, allowing us to discuss both the context in which wills were drawn up and how they mix generic with distinctive features in ways that can be tricky to interpret. Indeed, we concluded that is no small part of their appeal for researchers, one that invites deeper contextualisation and record linkage in an attempt to tackle all the questions that an individual will poses. We could probably have talked about this one will for the rest of the day, indeed I have a lot more to say about it, but that will have to wait for a future blog post – I will move on…

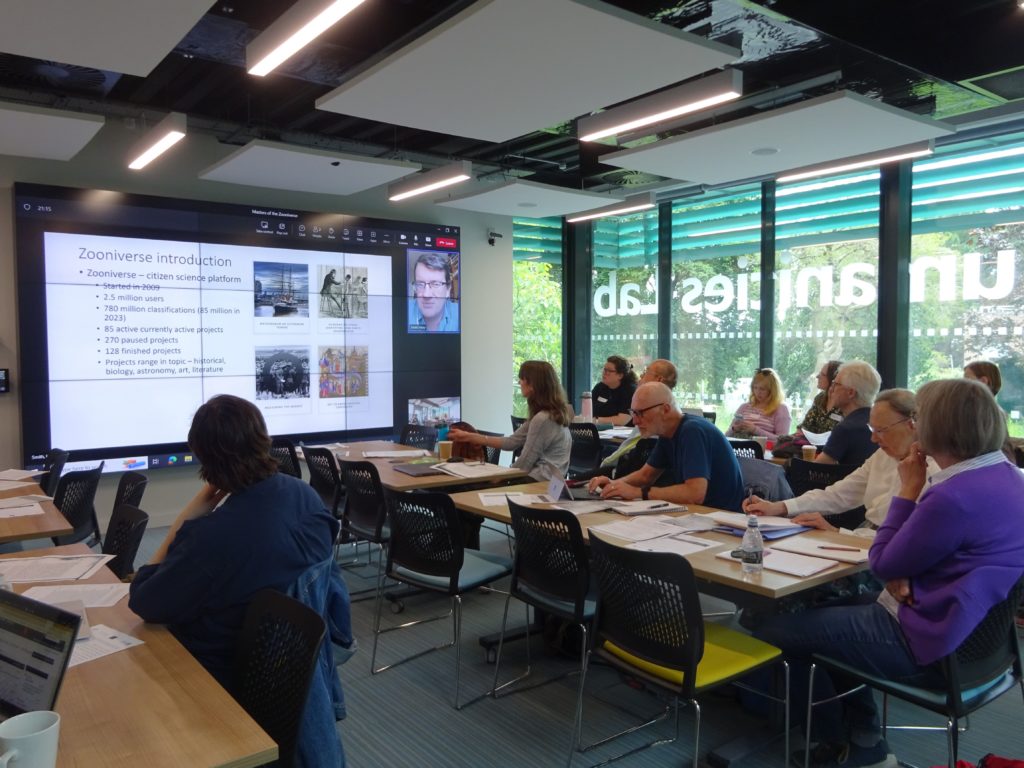

One of the most exciting parts of the days for me was that we were able to preview our Zooniverse site (currently near to completion). Harry Smith is responsible for creating and running our site so he introduced this crowdsourcing platform and explained how The Material Culture of Wills site will work. The Zooniverse platform allows volunteers to quickly start transcribing parts of our 25,000 transcriptions – on our site users are given an image from a PROB 11 digitised will, with lines of text that has been automatically generated by the HTR model underneath. The volunteer is then asked to check, correct or transcribe the line/s. Our workshop participants speedily mastered the basics and were not only able to give us vital feedback and suggestions for improvements to the interface, they also completed 1308 transcribing tasks before the end of the next week! This was a really encouraging debut and which bodes well for our official Zooniverse launch in the next few months.

Summary

As you can hopefully tell, the workshops flew by in a flurry of creativity and dialogue – we were delighted by how well both went. The chance to spend two days with like-minded researchers, all of whom share a fascination with, and appreciation of, the wealth of information that wills contain about the past was incredibly rewarding, and we plan to build on the success of these events in future. In the meantime, if you want to know more about how to locate and analyse early modern wills, please see the reading below and our growing list of research resources.

Arkell, N., Evans, and N. Goose, eds, When Death Do Us Part: Understanding and Interpreting the Probate Records of Early Modern England (Leopard’s Head Press, 2000). Essays which explain how the system of probate worked and discuss the different types of probate documents.

Digitising 25,000 wills: method and accuracy. Blog post by Harry Smith.

‘If my daughters will not be ruled’… Contingencies and Caveats in will-making. Blog post by Emily Vine.

Who was buried where in the early modern period? Blog post by Laura Sangha.

Lloyd Bonfield, Devising, Dying and Dispute: Probate Litigation in Early Modern England (Ashgate, 2012).

Elizabeth de Bold, ‘But by the Eyes of His Trustees’: the Emotions and Post-Mortem Strategies of Will-Writing in Restoration London, 1660–1700’, Cultural and Social History (online, 2023).

Amy Erickson, Women and property in early modern England (Routledge, 1995).

Martha C. Howell, The Marriage Exchange: Property, Social Place, and Gender in Cities of the Low Countries, 1300-1550 (Chicago, 1998).

Marcia Pointon, Strategies for Showing: Women, Possession, and Representation in English Visual Culture (OUP, 1997). Pointon shows that the relationship of women to the world of consumption was affective and imaginative as well as economic, bequests are a key source of evidence.

Alex Shepard, Accounting for Oneself: Worth, Status, and the Social Order in Early Modern England (OUP, 2015).

Keith Wrightson, Ralph Tailor’s Summer: A Scrivener, his City, and the Plague (Yale, 2011).