Posted by e.m.vine@exeter.ac.uk

26 November 2024This month’s post analyses the will of John Huggens or Huggyns, a ‘Capper’ or cap-maker who died in Gloucester in 1544.[1] Huggens’ will shows how just one type of object, the humble woollen cap, could underpin personal relationships and have multiple meanings within an individual’s life. Caps were a big part of Huggens’ world: making them was his trade, but they were also mentioned several times in his will as bequests to friends and family, and as gifts designed to recompense the overseers of his estate and those who nursed him in his final sickness.

Huggens the Capper

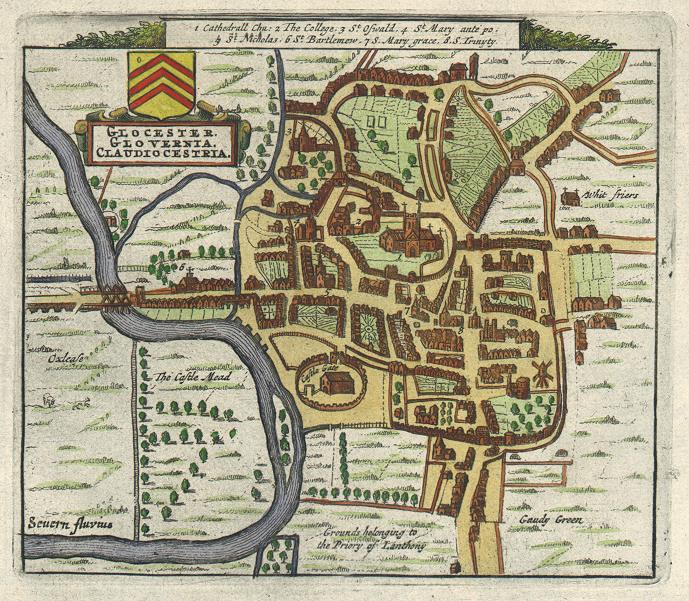

‘Capping’, the making or knitting of woollen caps, was linked to the English wool trade and was an important industry in early Tudor Gloucester, but it had begun to decline around the time that Huggens made his will. Records from early sixteenth-century Gloucester mention around nine principal cappers working at any one time, some of whom employed large numbers of people.[2] Huggens may have run a smaller operation, but he certainly had an apprentice, John Barret, who he left ‘thirtene shillinges foure pence’ to be paid once his obligations to Huggens’ widow and son had been fulfilled. Huggens’ encounters with other Gloucester cappers also appear in other historical records. In 1537, he informed against the Mayor of Gloucester and fellow capper Thomas Bell the Elder, claiming that Bell had called Bishop Latimer ‘a horesone heretycke’.[3] Huggens’ co-accuser was another capper, John Rastell, who was later named the overseer of Huggens’ will. Bell was likely at this time the chief capper in Gloucester – is it possible that Huggens and Rastell had ulterior motives for informing against their local competitor in this way?

Best girdles and best beads

It is of course quite possible that Huggens informed against Bell for matters of faith and conscience: Bell was a man of local standing and influence, he had spoken ill of a reforming Bishop, and he had perhaps exhibited traditional Catholic sympathies. But another feature of Huggens’ will, proved seven years after this incident, perhaps complicates Huggens’ alleged criticism of Bell – his mention of ‘beades’, a term almost always used to denote rosary beads at this time.[4] He left to his daughter-in-law ‘my wiefs beste girdle and hur beste beades’. But there was a caveat – his wife was still alive, and he clarified that ‘my wief shall have thuse of them during her liefe’. The bequest of beads that were envisaged to be in continual use thus suggests that Huggens or members of his family were certainly not committed reformers. Huggens also bequeaths money to his ‘gostly father’ Sir John Williams, which seems to be a reference to his priestly confessor.

Specifying bequests that his wife would have use of during her lifetime was a means of setting aside items as distinct from the residue of household goods that would go to his eldest son. He gave ‘to Johana the eldest daughter of my saide soon Rafe Huggyns my beste sylver sallte double gylte with a coover’ and to Rafe’s second daughter, also named Johana, ‘my secoonde sallte of silver parcel gyllte withe the coover’. But both these silver gilt salts, the best and second best, to the first and second Johanas, were to remain to the use of Huggens’ wife during her lifetime. ‘Same-name’ living siblings were mentioned more than once in this will: Huggens left a bequest to Thomas Bell the Younger, the half-brother of the aforementioned cap-maker Thomas Bell the Elder, of ‘a gowne clothe of pewke’ (a woollen cloth).[5] An additional cloth-based bequest, his ‘slyvelesse cote of Kentish clothe’ went to ‘the poore man called Thomas Shepparde’. That Huggens left a poor man a coat that he himself had owned and presumably worn suggests a degree of personal connection and consideration that goes beyond more expected charitable bequests of money.

‘one of my beste Cappes’

Alongside these bequests of gowns, coats, beads, girdles, and silverware, it is Huggens’ own caps that are a key feature of his will. Huggens left caps to a few different people, some of which he explicitly identified as having made himself. He left to John Stakes ‘a Button cap of the beste makynge’: a bequest that signals a desire for Stakes to receive a high-quality item, perhaps one of the better examples of his craftsmanship. He gave ‘to Katheryn Staninge one of my beste Cappes for her wearyng and lykwyse to Elizabeth Graunger I gyve an noother of my beste cappes for her wearyng for their paynes taken withe me in my sicknes’. These ‘beste cappes’ were gifted in recognition and gratitude for the women’s work in caring for him, presumably during the sickness that prompted him to make his will (he died, and the will was proved, around four months later). Both women had likely already been paid or reimbursed in kind for their care work, and these caps were likely an additional token of gratitude. They received the caps for their ‘wearyng’: as with the gift of the sleeveless coat to the poor man Thomas Shepparde, these bequests were practical and personal.

‘the beste cappe of my makyng’

Huggens asked that John Rastell, his fellow capper and co-accuser of Thomas Bell the Elder, be made an overseer of his will, and gave him ‘for his paynes’ in seeing the will performed ‘six shillinges eight pence and the beste cappe of my makyng for his wearyng’. That Rastell would receive the ‘beste’ cap emphasises the high regard with which the role of ‘overseer’ was esteemed, and the trust placed in Rastell to fulfil it. While Huggens appeared to have valued women’s care work as comparable to the labour of overseeing a will, he perhaps also wanted his fellow craftsman to receive a sample of his very best work. These ‘beste’ or nearly best caps were not only high-quality items designed to recognise and recompense the work of care or complex administration, but they were also personal representations of the labour of the testator’s own hands. Indicative of Huggens’ life’s work, they were chosen specially and designed for the named individual to use and wear, forming a tactile connection between testator and beneficiary. The considered dispersal of otherwise ordinary and ubiquitous woollen caps, became, in the context of the craftsman’s will, a means of ensuring the remembrance of the testator. The humble woollen cap was both a practical garment and a personal token that, in its bequeathing, fulfilled a similar function to the distribution of mourning rings.

T. Johis Huggyns

In dei nomine amen the xxth daye of the monethe of July in the yere of our Lorde god

a thousande ffyve hundred ffourty and foure I John Huggens Capper of the parryshe of the blessed Trynyty

in Gloucestre sycke of body but hole of mynde make my laste will in manner and forme hereafter folowyng ffirste

I bequeathe my soule to Allmyghty god, and my boddy to the earthe and to be buryed in the Cathedrall churche

yarde in Gloucestre before the Crosse the whiche Crosse was a place appoyented to preache / In primis I

will there be bestowed in breade at my buryeng emonges poore people twenty six shillinges eight pence And at

my monethes mynde in breade at my burying emonges poore people fourtene shillinges foure pence Item I gyve to the poore

people of the Bartholomeyes twelve pence in mooney. Item I gyve to Rafe Huggyns my Soon and to his heyres for

ever the howse that I dwell yn wch I boughte of maister Jenns provyded allwayes that my wief shall have the use

of hym and commodyty duryng hur lief and if my Sone Rafe Lacke heyres as god forbydde then I gyve the

saide house to my sonne John Huggyns and to his heires male and for lacke of heyres male I gyve hym to the Reparacion

and maynetenance of the weste bridge. Item I gyve to Elizabethe Huggyns my sonnes wief my wiefes beste gyrdle

and hur beste beades So that my wief shall have thuse of them during her liefe Item I gyve to my saide Sonne Rafe

Tenne pounds Item I gyve to my saide Sonne John Huggens ten poundes in moonney whiche shalbe delyvered by my

Executours withyn twelve monethes into thandes of John Rastell and my sonne Rafe ffyve poundes a pece and they

to delyver this mooney all hallfe or peicell meale to my sayde soon John when their dyscretion shall [illeg] wth the

Assent and consent of Bothe parties Item I gyve to Johana the eldest daughter of my saide soon Rafe Huggyns my beste

sylver sallte double gylte wt a coover to be delyvered to hur at the daye of her mariage yf she lyve so longe Item I

gyve to Johana his secoonde daughter my secoonde sallte of silver parcell gyllte withe the coover and to be delyvered

at the daye of hir mariage provyded that my wief shall have thuse of them duryng her lyef, and afterwards

to be in the safe custody of my saide soon Rafe for thuse of his children Item I gyve to mayster Thomas Bell the

younger a gowne clothe of pewke the price of the yarde seven shillinges and six pence or an angell a yarde if the

clothe be so worthe Item I gyve to my wief to Rafe my Sonne and to his wief and to my sonne John to every of

them a blacke gowne Item I give to every aultar of the sayde churche twelve pence Item I gyve to the poore man

called Thomas Shepparde my slyvelesse cote of Kentish clothe Item I gyve to Katheryn Staninge one of my beste

Cappes for her wearyng and lykwyse to Elizabeth Graunger I gyve an noother of my beste cappes for her

wearyng for their paynes taken withe me in my sicknes Item I gyve to John Huggyns the porter of

Ayles yate my oulde ffox gowne Item I gyve to John Stakes a Button cap of the beste makynge

Item I gyve to John Barret my prentice thurtene shillinges foure pence wch he shall receave when he hathe

fullfylled his covenantes wt my wief or wt my soon Ralf Item I doe remytt to Abell Heryott the debtes whiche

ys betwene hym and me Item I gyve to Sir John Williams my gostly father for his paynes taken wt me six

shillinges eight pence Item I will that maister John Rastell and my Soon Ralf Huggyns shalbe my overseers

to se this my laste will performed, and maister Rastell to have for his paynes six shillinges eight pence

and the beste cappe of my makyng for his wearyng The Resydue of my goodes unbequeathed I gyve

holy to [?Seynche] Huggyns my wief, whome I make my sole executrice, Item I gyve to twelve poore men

twelve blacke gownes; This bearing wytnes John Sandforde, Henry ap Rice, Abell Haryott wth

oother mo

[1] PROB 11/30/274 Will of John Huggens or Huggyns, Capper of Blessed Trinity Gloucester, Gloucestershire, 01 December 1544.

[2] ‘Medieval Gloucester: Trade and Industry 1327-1547’, in A History of the County of Gloucester: Volume 4, the City of Gloucester, ed. N M Herbert ( London, 1988), British History Online https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/glos/vol4/pp41-54

[3] Henry VIII: January 1537, 26-31′, in Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, Volume 12 Part 1, January-May 1537, ed. James Gairdner ( London, 1890), p.139.

[4] Oxford English Dictionary, s.v. “bead (n.), sense I.1.b,” June 2024, https://doi.org/10.1093/OED/9285137756.

[5] Chris Galley, Eilidh Garrett, Ros Davies and Alice Reid, ‘Living Same-Name Siblings and British Historical Demography’, Local Population Studies 86, (2011) pp.15-36. 10.35488/lps86.2011.15.