Posted by e.m.vine@exeter.ac.uk

25 March 2025Content Note: This blog post discusses enslaved people

This month’s post takes us on a journey from London to Calcutta via the South Atlantic island of St Helena, navigating the complex administration of the wills of those who died thousands of miles from England, the movement of people and property, and the blurred boundary between the two.

Most of the wills in our sample – wills that were proved before the highest probate court, the Prerogative Court of Canterbury (PCC) – were made by individuals who lived in southern England and Wales. Where we have testators from northern England, it is generally because they owned goods in both the northern and southern province, as the PCC had the right to grant probate in such cases. The PCC also contains the wills of individuals who died abroad, such as sailors, soldiers, or East India Company employees, or those who were resident overseas but owned property in Britain. Wills in our sample were accordingly made by testators who lived in locations as distant as Amsterdam, Barbados, South Carolina, Cape of Good Hope, Ceylon, Newfoundland, and the Ottoman Empire.

Elizabeth Thomlinson, described as a widow of Calcutta, was ‘sick and weake in body’ when she made her will on 13 June 1720.[1] She died in September of that year. In the days following her death, the witnesses to her will and its codicil testified to the document’s legitimacy in front of ‘the President and Counsel in Bengal for affairs of the Honr United Company of Merchants of England trading to the East Indias’. Yet her will would not be proved in London, before the PCC, for another five years.

A man of whom ‘little need[s] to be said’

When Elizabeth died, she had not been in Calcutta long. She had arrived in January 1720, with her East India Company chaplain husband Rev. Joshua Thomlinson, of whom one biographer notes ‘little need[s] to be said […] His career in India lasted a little over four months, and his widow barely survived him’.[2] That Joshua died so quickly after his arrival in Calcutta meant that he barely got to take up the Church position that he had been appointed to. In his own will he was described as ‘being sick and weak of Body’: he died within three days of making it, on 29 May.[3] The makeshift or hurried nature of the circumstances in which Joshua made his will were confirmed by the witnesses, who ‘declared [it] to be the Testators’ Last Will and Testament where no Stampt paper is to be had’.[4] Elizabeth, also sick at this point, made her own will within two weeks of her husband’s death.

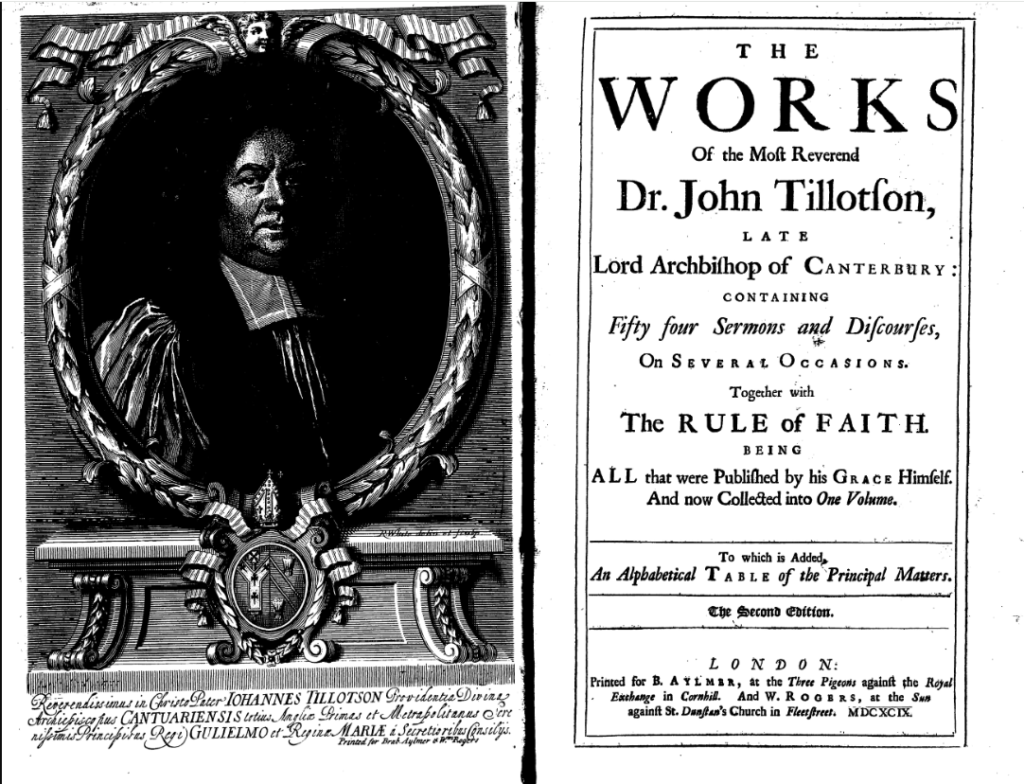

Elizabeth clearly anticipated her own mortality, and quickly adapted to the administrative tasks of widowhood, using her will to distribute some of Joshua’s remaining effects. She disposed ‘of all my deceased husband the Reverend Joshua Thomlinson his Library of books’ including ‘two volumes new in folio of Doctor Tillotsons works the whole duty of man in folio’, and ‘unto Thomas Coales his choice of thirty bookes out of what books remaines’. She left Joshua’s remaining books, including commentaries on the bible, and books in ‘Latin Greeke Hebrew’ to ‘the Church of Calcutta’. She also gave ‘forty rupees towards a Charity school in Calcutta’ – a relatively small amount, considering that she left ten times that amount to Samuel Feake, the Governor of Bengal. Joshua had previously left ‘Eighty Rupees’ ‘towards setting up of a Charity School in this place’. Elizabeth lived for another three months, making a codicil to her will a week before she died, in which she asked her executor ‘to build a Tomb over my husbands and my Grave’.

The Thomlinsons as travellers

The Thomlinsons had not travelled directly from England to Calcutta that fateful year. Joshua had spent twelve years as an East India Company chaplain on the island of St Helena, an English colony on a remote volcanic outpost in the South Atlantic Ocean and ‘stopping-off point’ on the route to India. Elizabeth’s brothers, John and William Worrall, and their families, still lived on St Helena, and many of her goods went to them. She desired ‘that all my wearing apparell may be sent to my brother John Worrall at St. Helena which I give between his wife and daughters excepting one black sattin Gowne and petticoat and a black scarfe which I give to my sister in law Martha Worrall’. She also gave to her niece ‘all my plate that is to say Two Tankards Twelve Spoons one salver three Casters and one porringer also One Table Cloath and sixteen English Diaper Napkins’. Calcutta and St Helena were 7000 miles apart as the crow flies, a voyage round the south of Africa that would have taken months. It would have been a considerable undertaking to ensure that Elizabeth’s clothing, plate, and spoons reached their intended beneficiaries halfway across the world. Both Elizabeth and Joshua’s wills acknowledged that they did not know if all their beneficiaries on St Helena were still alive; the danger and separation inherent in East India Company life is apparent in both documents.

The Thomlinsons as slave owners

The Thomlinsons, like almost all English families on St Helena, were slave owners. The English had enslaved people on St Helena since they had colonised the island in 1659, forcing them to work on plantations of indigo, coffee, and sugar, or in domestic labour.[5] Elizabeth’s will contains this brief sentence: ‘I give my slave wench Nanny which I left along with Mrs Elizabeth Lacy on St Helena’s her freedome’. By the 1730s, ‘wench’ was a dehumanizing term increasingly used to refer to women of African descent.[6] It is striking that, as in other wills that mention enslaved people, Nanny is discussed in a similar manner to other moveable property.[7] Her existence on St Helena is recognised in the sentence which comes sometime after Elizabeth’s attempts to return her spoons and napkins to that same island. Her freedom had not been granted when the Thomlinsons had first travelled to Calcutta. Perhaps Nanny had been attached to a household that they had intended to return to, or perhaps she had been ‘gifted’ to Mrs Lacy in their absence. She was freed perhaps only when Elizabeth Thomlinson was faced with the incontrovertible truth that neither she nor her husband would live to leave India. Perhaps, reckoning with her approaching death, Elizabeth’s decision to free Nanny was made in a moment of conscience. This request was made in the same clause as Elizabeth’s gift to the charity school: like many Christian contemporaries, she had no objection to enslaving others, but paradoxically viewed granting an enslaved person their freedom as a charitable act, a positive good.

The Thomlinsons’ wills hint at many of the complexities and contradictions in the lives of the English men and women who travelled in the employ of the East India Company. Joshua described himself as a ‘Minister of Gods word’, he and his wife left bequests to charity schools and churches in Calcutta. As a man of religion and learning, Joshua’s library was carefully packed up and transported across the ocean. As a married couple, they faced the uncertainty of travelling thousands of miles and separation from family, and the realised fear of sickness and premature death. Their life in the colonies also enabled them to ‘own’ enslaved people in a manner that had no legal basis in Britain itself. As slaveowners, they granted freedom to the woman named Nanny almost as an afterthought, and only once they had secured their own tablecloths, plates, and spoons.

Tm

Eliza Thomlinson

In the Name of God Amen

I Elizabeth Thomlinson widow of Calcutta being sick and weake in

body but of sound and perfect memory praised be God Do make

and ordaine this to be my last Will and Testament as followeth –

Imprimis I will and direct that all my Just debts and ffunerall

charges be paid Item I give and bequeath unto the honorable

Samuel ffeake Esqr the sume of ffour hundred Rupees Item I

give and bequeath unto the Worshippfull James Williamson Esqr

[new page]

the sume of One hundred and sixty Rupees Item I give and bequeath unto

my nephew Thomas Swallow the sume of Two thousand and four hundred

rupees which I desire may be deposited in the hands of the Honourable

Samuel ffeake for his maintenance and education which I request the

honourable Samuel ffeake Esqr will be pleased to take care of Item I

give and bequeath unto my deced husband the Reverend Mr Joshua

Thomlinson his neeces the daughters of his eldest sister who he

hath sent for out of England the sume of Nine hundred and sixty rupees

being the like sume which my said husband hath given them in his last

will and I do give it on the same Conditions which he hath done in

his will but in case neither of them doth come out of England to this

place then I give unto my said husbands eldest sister her daughters

each of them the sume of Two hundred and forty rupees or Thirty

pounds sterling Item I give unto my said husbands twoe sisters each

of them One hundred and sixty rupees or Twenty pounds Item I

give and bequeath unto my brothers John and William Worrall on

the Island of St Helena’s each of them the sume of Eight hundred

Rupees or one hundred pounds sterling But in case my brother

William Worrall is dead then I give the above mentioned Eight

hundred rupees or one hundred pounds between his Children

to be equally divided amongst them Item I give unto my sister in law

Martha Worrall the debt which she owes me and also the sume of

one hundred and sixty rupees Item I give unto my brother John

Worrall his twoe eldest daughters the sum of ffour hundred rupees

or ffifty pounds each Item I give unto my neece Elizabeth eldest

daughter of my brother John Worrall all my plate that is to say Two

Tankards Twelve Spoons one salver three Casters and one porringer

also One Table Cloath and sixteen English Diaper Napkins Item I

give to my brother John Worrall what debts he owes me Item I give

unto my Nephew Joshua and William sonns of my brother John

Worrall the sume of Three hundred and twenty rupees each and

to his daughter Margaret I alsoe give Three hundred and twenty

Rupees Item I give unto my brother William Worrall his Children

each of them forty pounds or three hundred and twenty rupees

in case their father William Worrall is alive Item I give my slave

wench Nanny which I left along with Mrs Elizabeth Lacy on St

Helena’s her freedome Item I give forty rupees towards a

Charity school in Calcutta Item I give and dispose of all my deced

husband the Reverend Joshua Thomlinson his Library of books as

followeth (vizt) I give to the honourable Samuel ffeake Esqr three

volumes of Doctor Sherlocks works his discourses of a future state

death and Judgement six volumes of Doctor Ofspring Blackhall’s

works two volumes new in folio of Doctor Tillotsons works the

whole duty of man in folio six volumes of my Lord Clarendons

Works Two Volumes of Doctor Derhams works (vizt) his astro

Theologie and Phisico Theologie and any other books which he

shall have a fancy for I give unto the Worshipfull James Williamson

out of the remainder of my husbands books the same number of books

which I have given Govr ffeake such as he shall like best. I give unto

my brother John Worrall Doctor Sherlocks sermons and one old

volume of Doctor Tillotsons sermons I give unto Thomas Coales

his choice of thirty bookes out of what books remaines and the

[new page]

remaining book such as Latin Greeke Hebrew &c also all the Commentaries

on the Bible I give to the Church of Calcutta Item I desire that all my wearing

apparell may be sent to my brother John Worrall at St. Helena which

I give between his wife and daughters excepting one black sattin

Gowne and petticoat and a black scarfe which I give to my sister in

law Martha Worrall Item I give and bequeath all the remainder

part of my estate to my brothers John and William Worrall to be

divided equally betweene them Item I appoint and desire the

Honourable Samuel Feake and the Worshippfull James Williamson to

be Trustees to this my last Will and Testament and lastly I do

hereby Will and ordaine this to be my last Will and Testament

revokeing disannulling and disallowing all of the former Wills &c

made by me heretofore In witness whereof I have hereunto sett

my hand and seal in Calcutta this 13th day of June 1720. Eliza

Thomlinson. Signed sealed and declared to be the last Will and

Testament of Elizabeth Thomlinson in the presence of us after

interlineing in the ^ first side begining of the sixteenth line the words (and

four hundred) Tho Coales Rob. Broadfoot Richd Cleaverlee

A Codicill made this fourth day of September Anno

Dni 1720 by me Elizabeth Thomlinson to my last will and

Testament dated in Calcutta the 13th day of June 1720. That is to

say, (I will and desire my Trustees the honoble Samuel Ffeake

and the Worshipfull James Williamson nominated in my said

Will to build a Tomb over my husbands and my Grave In witness

whereof I have hereunto sett my hand and seal in Calcutta the

day and yeare abovewritten E Thomlinson signed and sealed

in the presence of Tho Coales Robt Broadfoot ^

[left margin]

Messrs Thomas Coales Robert

Broadfoot and Richard Cleaverlee the

Witnesses to the last Will and Testamt

of Mrs Elizabeth Thomlinson deced as

also Messrs Thos Coales and Robert

Broadfoot Witnesses to the Codicil

next to said Will appealing before

us the President and Counsel in

Bengal for affairs of the Honr United

Company of Merchants of England

trading to the East Indias, in the

Consultation Room in ffort William

this 12 day of September 1720 and

being sworn on the holy Evangelists

the former three persons declare

swore oath that they saw the Testator

sign seal and declare this to be her

last Will and Testamt and the two

other likewise declare upon oath that

they saw her sign to the above Codicil

and that she was then perfectly in

her senses and that they saw each

her sign as Witnesses

Sam Feake W Collett

Edw Cuso Wm Spencer

John Eyre

[1] PROB 11/606/129, Will of Elizabeth or Eliza Thomlinson, Widow of Calcutta, East Indies, 18 November 1725

[2] Eyre Chatterton, A History of The Church Of England In India since the early days of the East India Company, (Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge, 1924) p.72.

[3] PROB 11/594/384, Will of Joshua Thomlinson, Minister of Calcutta in Bengal, East Indies, 20 December 1723

[4] PROB 11/594/384, Will of Joshua Thomlinson, Minister of Calcutta in Bengal, East Indies, 20 December 1723

[5] Kathleen Wilson, Rethinking the Colonial State: Family, Gender, and Governmentality in Eighteenth-Century British Frontiers, The American Historical Review 116 (2011), 1294–1322 at 1307.

[6] See Karen Cook Bell, “‘A Negro Wench Named Lucia’: Enslaved Women during the Eighteenth Century.” in Running from Bondage: Enslaved Women and Their Remarkable Fight for Freedom in Revolutionary America, (Cambridge University Press, 2021), pp.20-43, at p.22.

[7] See Ellen Filor, ‘The intimate trade of Alexander Hall: Salmon and slaves in Scotland and Sumatra, c.1745–1765’, in Margot Finn and Kate Smith eds. The East India Company at Home, 1757-1857, (UCL Press, 2018) pp. 318-332