Posted by e.m.vine@exeter.ac.uk

22 April 2025This month’s post has been inspired by conversations with the project’s Creative Fellow, composer, arranger, performer and lyricist Chris Hoban. Chris has recently been analysing the wills of sextons and thinking about the symbolism of the body being laid to rest. This is a longstanding interest of his – you can listen to one of his songs on this topic, The Old Lych Way, here. You can find out more about Chris’s work with the project here, and in his recent reflection diary.

While early modern will-makers often stated their wishes for their burial, testators gave varying levels of detail. Many simply entrusted funeral logistics to the discretion of the executors of their will, asserting only their wish to be buried ‘decently’. Others specified their hopes to be buried in the churchyard in the parish ‘in which I now dwell’.

By comparison, the will of James Liddell, a gentleman who died in the Wiltshire village of Lacock in 1664, is unusually detailed in establishing his specific plans for the interment of his body.[1] While religious language in wills is often formulaic, many of Liddell’s provisions for his body and soul, beginning with his ‘blessed assureance of a Joyfull resurrection’ appear as more personal and precise articulations of piety. Liddell’s bequests planned not only for his own Christian burial, but for the future burials of his fellow parishioners and ‘gods people’.

Wishes fulfilled ‘for loves sake’

James firstly stated his desire ‘to be buryed in the Chancell of the parrish Church of Laycocke by my deare wife who lyes buryed under the Communion Table’. It appears that Liddell made a special request to be reunited with his wife in death: ‘And this Charitie I desire of Sherington Talbott Esquire patron of the said Church for loves sake not to deny me giveing him twenty shillings for his good will therein’. Colonel Sharington Talbot was part of the Talbot family who owned the country house of Lacock Abbey, and much of the village itself. Twenty shillings was a ‘token’ remuneration: Liddell, a gentleman of good standing in the village, instead appeals to Talbot’s good will, his ‘Charitie’, and his love to permit burial in this prominent setting. Later in the will he asked that Talbot also be paid ‘such herriotts’ (payments to a landowner) ‘which upon my death shalbe due unto him’.[2]

Having established his intentions for his body’s committal ‘to the earth’, Liddell’s will then turned to his ‘worldly goods’. He left several items of clothing to Thomas Lyddall: ‘my medley cloake my rideing Coate and my best cloath suite’. Some of his ‘deare’ wife’s belongings were given to a Mistress Cutler: ‘my wives new rideing suite a little silver bottle 3 silver spoones and a little one of silver my wives wedding ring and a little silver salt’. He also gave ‘unto my good brother Mr Richard Ashleyes yongest daughter by his last wife the imbrodered purse’. Seventeenth-century embroidered purses were not usually used to carry money. They may instead have been used to hold mirrors, or sweet-smelling dried flowers that were designed to mask body odour.[3] The items that Liddell singled out for mention were largely decorative or valuable (including ‘best’ or ‘new’ clothing) or of personal or sentimental value (his wife’s wedding ring). The rest of his ‘goods Chattells and moveables’ were to be left to his ‘wellbeloved Cousins in Christ’.

‘The carryers of my body to the grave’

Alongside the careful dispersal of his ‘worldly goods’, Liddell discussed his funeral plans in greater detail. The minister Mr Barnes would preach his funeral sermon, and £1 was left for his troubles. He gave two shillings each to ‘The carryers of my body to the grave’ and, unusually, named the six men that he hoped would perform that duty. He left six shillings eight pence ‘To the sexton’, who would usually be tasked with grave-digging, but perhaps in this instance with opening the vault underneath the communion table.

His concern for appropriate burial extended to his parish in life and death. He wished to leave ‘to any hundred twenty poore people 6li’ – a version of the traditional funeral dole for the poor. As mentioned in a previous blog post, the local poor ‘defined themselves by their willingness to accept’ funeral doles.[4] When I discussed this will with the project’s Creative Fellow Chris Hoban, Chris pointed out that 120 was a biblically significant number. 120 was the age at which Moses died, and the number of years God waited for repentance before sending The Flood, during which time Noah built the Ark. There were 120 trumpeting priests at the dedication of Solomon’s temple, and Acts 1:15 refers to a gathering of ‘about an hundred and twenty’ disciples in Jerusalem.[5] In Liddell’s gesture to the symbolism of 120 disciples, was he attempting to create a ‘New Jerusalem’ in his small parish in Wiltshire?[6]

‘the blacke cloath that Covers my body’

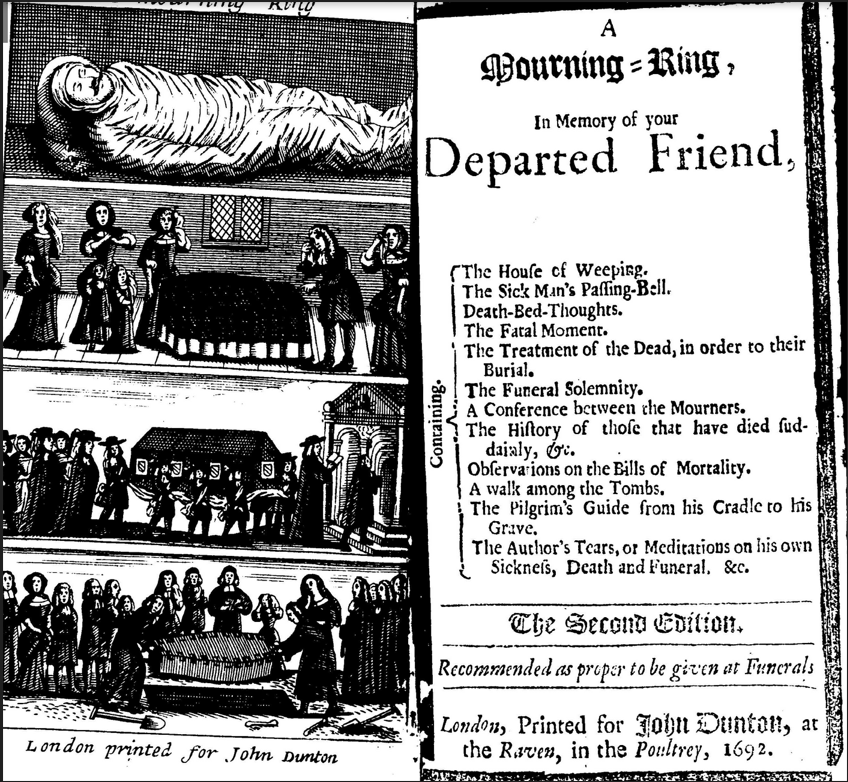

The concept of a ‘New Jerusalem’ was a popular idea amongst reforming Protestants in seventeenth-century England, associated with a utopia-style society of true believers that would come into being after Judgement Day. The process of making a will undoubtedly prompted pious individuals to meditate on judgement and resurrection, the fate of their body and soul, and their relationship to the community of believers. Liddell’s final burial request was his most striking, stating: ‘the blacke cloath that Covers my body to the grave I give to the parrish of Laycocke to be kept by the church=wardens thereof for the tyme being to be a Covering for the bodyes of gods people to their burialls as long as it will last’.

It was common for funeral palls to be owned by a community (such as guilds or worshipful companies). The photograph above depicts the hearse cloth used at funerals of members of the Merchant Taylors’ company, one of the Greate Twelve Livery Companies of London. Liddell specified that his own black funeral pall should be donated and used as needed by other parishioners, specifically ‘the bodyes of gods people’. In positioning himself alongside fellow believers, this clause is also exclusionary and perhaps stood as an attack on those with Catholic leanings. When Chris Hoban read this will, he commented on the significance of the donated funeral pall being in use ‘as long as it will last’: perhaps denoting Liddell’s reflection on the fact that all things decay, a contemplation upon human mortality, and the transience of both people and traditions.

‘And soe I end to gods glory’

The conclusion of Liddell’s will mirrored the pious language that opened it: ‘And soe I end to gods glory’. The legal document was concluded, as was, in due course, Liddell’s own mortal life. Like many of the wills we are analysing as part of our study, this example is deeply intentional in its choice of language and bequests. Through the final document he left, we get the sense of a devout man who had thought carefully about the positioning of his body and soul within the sea of time. Musing on eternity and mortality, Liddell hoped to be laid to rest alongside his dear departed wife, he was reassured about the prospect of ‘Joyfull resurrection’, and his final offering to his parish – the hearse cloth, in all its ephemerality – was envisaged for the use of fellow believers for future generations, or at least, for as long as the gift would last.

Full Transcription of the will of James Liddell, Gentleman of Lacock, Wiltshire, 04 June 1664, PROB 11/314/179

Tm Jacobi Liddell

In the name of God Amen I James [Liddell]

of Laycocke in the County of Wilts gent being of good health and

perfect memory I most humbly thanke my heavenly ffather [illeg]

ordaine and make this my last will and testament in manner and forme

following ffirst and before all other things I give and bequeath my

Soule into the hands of Almighty god my creator and of Jesus Christ

my redeemer through whose blessed merrittes death “ “ passion and medi=

acion I trust to be saved and my sinnes pardoned And that of my hea=

venly fathers free grace and mercy without any meritt of myne My

body I committ to the earth in a blessed assureance of a Joyfull

resurrection through Jesus Christ unto eternall life the same to

be buryed in the Chancell of the parrish Church of Laycocke by my

deare wife who lyes buryed under the Communion Table And this

Charitie I desire of Sherington Talbott Esquire patron of the said

Church for loves sake not to deny me giveing him twenty shillings

for his good will therein As for my worldly goods I bequeath and

dispose of them as followeth First I give and bequeath unto my

Sister

[new page]

Sister Anne Webster 100li of lawfull English money To Thomas Lyddall

20li To him more my medley cloake my rideing Coate and my best cloath

suite To Symon Bellamies three Children 30li And to himselfe 2li To any

hundred twenty poore people 6li To old Mr Talbot 1li To Sir John 1li

To Mrs Meryall Talbott 1li To young Webster my sisters sonne in lawe

5li To Grace Hancocke her selfe 20li To her three children tenne pound

a peece To my Cousin Dennise sister in the North 5li To Mr Barnes for

his funerall Sermon 1li To Margarett Fluellen 1li To Dennis & Henry

Each of them = 20li a peece to their wives 23s a peece My buriall Twenty pounds The carryers

of my body to the grave 2s a peece To the sexton six shillings eight pence

The carryers to be Peter Oliffe John Thomas John Ducke Robert Moore John

Baker and George Dummer To Mris Cutler my wives new rideing suite

a little silver bottle 3 silver spoones and a little one of silver my wives

wedding ring and a little silver salt To her children tenne pound To my

brother Ashley 1li To my sister Hancocke 1li To Mr John Hancocke the

Poticary 1li To my Cousen Denises children 5li amongst them To my Cousin

Henry Daughter 1li And further the blacke cloath that Covers my body

to the grave I give to the parrish of Laycocke to be kept by the church=

wardens thereof for the tyme being to be a Covering for the bodyes

of gods people to their burialls as long as it will last All which Lega=

cies my desire is That my said executors and overseers hereafter na=

med shall pay and render, to them and every of them the said

sommes of money within fower monethes after my decease Item

I give unto my good brother Mr Richard Ashleyes yongest daughter

by his last wife the imbrodered purse And to my Cousin Westbere his

eldest daughter 1li Alsoe desireing my said executors to discharge and

pay unto Mr Talbott such heriotts which upon my death shalbe due

unto him for the livings in Charleton which John Smith holdeth Last

of all the rest of my goods Chattells and moveables not hereby given or

bequeathed My Legacies debts and funeralls discharged I give and be

queath to my welbeloved Cousins in Christ Mr Dennis Lyddall and Henry

Lyddall his brother whome I ordaine and make my sole and only ex=

ecutors of this my last will and testament desireing them and eyther

of them to be just and true in the performance thereof appointing my

welbeloved friends George Dummer of Laycocke Clothier and Grace

Hancock of the same widdow to bee my overseers to ayd and assist them

herein giveing to my said overseers and eyther of them 10s a peece

for their paynes And soe I end to gods glory renounceing all

other wills I declare this as my last will and Testament Signed

with my hand and Sealed with my Seale this 22th of September

1663 In the presence of Ja: Liddell Sealed signed and acknow:

ledged as my last will and testament in the presence of Tho:

Hancock Robert More Grace Hancock her marke Grace Handcock

her Children

[1] PROB 11/314/179, Will of James Liddell, Gentleman of Lacock, Wiltshire, 04 June 1664

[2] Oxford English Dictionary, “heriot (n.),” December 2024, https://doi.org/10.1093/OED/4283780319.

[3] ‘Object type’ description, https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O13586/purse-unknown/

[4] David Cressy, Birth, Marriage, And Death: Ritual, Religion, and the Life-Cycle in Tudor and Stuart England, (Oxford University Press, 1997), p.444.

[5] King James Bible 2 Chronicles 5:12, and Acts 1:15-26.

[6] See our colleague Dr Laura Sangha’s discussion of the idea of a ‘New Jerusalem’ here: https://manyheadedmonster.com/2015/03/16/aspiring-to-a-new-jerusalem-how-to-reform-a-society-part-i/