Posted by e.m.vine@exeter.ac.uk

28 October 2025Content note: this post discusses child loss and death in childbirth.

As a project team we’ve now spent two years carefully reading and analysing hundreds of early modern wills. To a certain extent we’ve become very familiar with them: we have a sense of what we might find, how bequests are usually phrased, and we can generally predict some of their more formulaic aspects. But we still come across individual wills that stop us in our tracks.

This month’s post looks at one such will, that of Margery Gadyng, a ‘Wife’, who died in 1540.[1] The vast majority of women who made wills in early modern England were widows, or had never married, as married women’s property in this period belonged to her husband under the laws of coverture. While married women could make a will with their husband’s consent, in practice, they rarely did so.[2]

‘licensed by her said husband’

Margery Gadyng had been married twice, and since her second husband Richard was still alive when she died, she accordingly made her will as ‘licensed by her said husband’ (with his permission). It was perhaps because she had had a previous marriage, and children, before marrying Richard Gadyng, that she had sought and been granted permission to set forth her own wishes as separate from her second husband’s. Yet Margery’s unusual will was also brought into existence because of the sudden and tragic nature of her early death.

Margery Gadyng died in childbirth, having previously given birth to at least five children (at the time of her death, three were living). Her will was nuncupative, meaning she declared her wishes orally to witnesses, rather than it being formally written down by a scrivener. Nuncupative wills were generally made when an individual was on their deathbed. This means we get more of an insight into the circumstances surrounding death than anticipatory wills, which tended to deploy formulaic phrases, including that the testator was ‘sick in body’ but ‘sound of mind’, and that they were mindful that death was inevitable, but the timing ‘uncertain’.

‘in the presence of Diverse honest women’

We know then that Margery Gadyng died ‘in her last labour of child’ and that she ‘declared her will in the presence of Diverse honest women being there aboute her for the necessitie of a woman in her case’. In other words, she dictated her last will and testament to the women who had come to assist her in childbirth, who included among others a midwife, her household servants, and her mother. The birthing chamber was a traditionally female space, it appears that her will was, in part, a means of conveying her wishes, and a final message, to her husband, who ostensibly was not present when she died. Margery accordingly left ‘her hert and love to her said husband Richard Gadyng’—a striking and unusual phrase, a last farewell to the spouse she would not see again—and asked that he ensure she was buried next to her two deceased daughters, Mary and Jane.

‘be good to them her children’

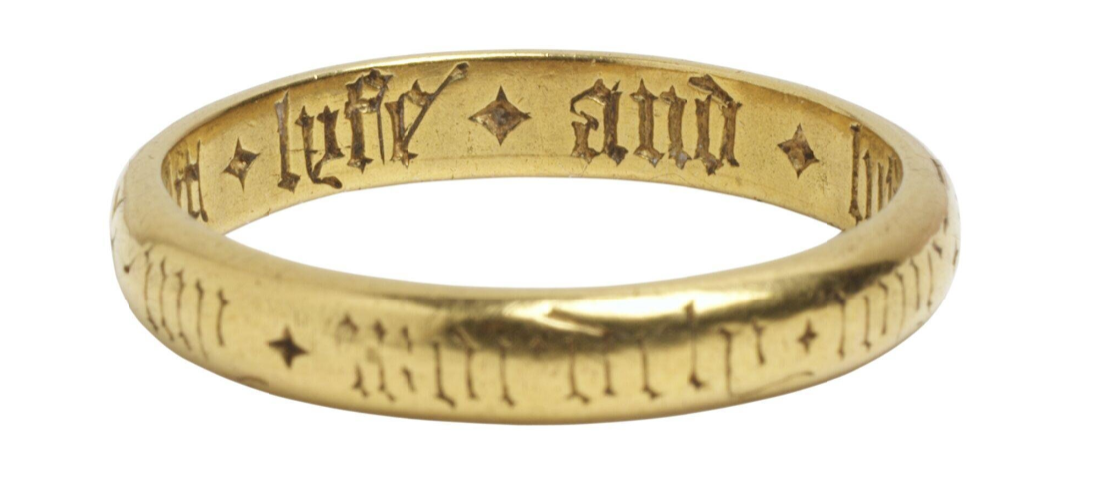

Margery also had two living daughters: Florence, who she left a bequest of her ‘fyrst weddyng Ryng’ and Margerye, who she left a bequest of her ‘second weddyng Ryng’. These two rings, alongside their emotional significance, may have fallen into the category of Margery’s own personal property and ‘paraphernalia’, which would allow her to dispose of them as she saw fit.[3] Other personal property included ‘her Gowne ffurryd with Calaber [squirrel fur] and her best kirtill of worsted [a wool gown]’, items of clothing which were left to her mother, who was also present when she died. Margery asked that her husband ‘be good to them her children’ (implying that Florence and Margerye were daughters from her first marriage) ‘and not to lett them come in other Strange kepyng’. In declaring her final will, Margery not only communicated her burial wishes and dispersed her property, she also acted to ensure the future care of her eldest children, who after her death would have no living biological parents.

To her infant son ‘Erasmus Gadding’, ostensibly the son of Richard, and young enough to be living with a wet nurse, she left ‘her Cheyne of gold that she was wont to weyre for a girdyll with all her joie and comfort beseching god to send hym and his ij Systers grace and good fortune’. She allocated all three of her living children items of gold jewellery that she wore regularly, and used her final message to convey her love for her children, and her hopes that God would bless them.

‘honest wemen… also witnesses therof’

As well as the heartfelt references to her children, the final bequests of Margery’s will are among the most poignant. She left small bequests to six named women. Five of these women, including ‘mother Bates the mydwif’, received ‘a vale and Rybyn’, while ‘Mestres Toxton’ received ‘a paire of beides’ (probably a rosary).[4] ‘Mestres Toxton’ was perhaps a closer friend or relative: the rosary was another gift of one of Margery’s personal items, one which was of spiritual significance, designed to be held and used on a daily basis, and kept close about one’s person. Like the rings and girdle this bequest created a very personal and haptic connection between testator and beneficiary. The five gifts of ‘a vale and Rybyn’ to the five other women, including the midwife, are more intriguing. Both the veil and the ribbon were probably small pieces of fabric, unlikely to be particularly valuable, although the ribbon may have been made of silk or satin, and designed to trim or decorate a garment.[5] It is possible that the veil was some form of mourning veil. These bequests could also fall into the category of small ‘tokens’: a small gift that may have had more sentimental than monetary value, or which was given in the hope that the beneficiary would remember the gift-giver.

The end of the will noted that these six women were the ‘honest wemen which be legatrices in this present Testament’ and had ‘been also witnesses therof’. In other words, these six beneficiaries were among the women who had come to assist Margery when she went into labour, who had cared for her when it became apparent that she was dangerously sick, and who had witnessed her spoken will, delivered in desperate circumstances. It is possible that one of the women had later written down Margery’s will, or that the presence of several corroborating witnesses could confirm the content of what Margery had said. While her husband Richard would execute the will, Margery invested significant responsibility in the women around her to commence this process.

Margery Gadyng’s will is remarkable in many ways: it was unusual for a married woman to make a will, and for a will to provide such a detailed sense of how an individual died, and who was in the room when it happened. It is also striking to have so many poignant expressions of emotion. Margery experienced some desperately sad circumstances, yet in what would be her final message, there are also expressions of love, and hope: ‘her hert’ left to her husband, the ‘joie’, ‘comfort’ and blessings of good fortune bestowed upon her cherished children, and the tokens of gratitude to the women who were with her in her final moments, who cared for her, and who were wholly trusted to make her final wishes known.

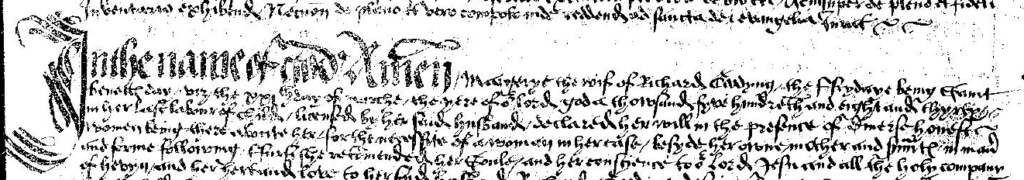

Full Transcription of the Will of Margery Gadyng, Wife, 10 July 1540, PROB 11/28/153

In the name of god Amen Margerye the wif of Richard Gadyng the ffridaye being Sainct

benettes day viz the xxjth day of marche the yere of our lord god a thowsand fyve hundreth and eight and thyrty

in her last labour of child licensed by her said husband declared her will in the presence of Diverse honest

women being there aboute her for the necessitie of a woman in her case besyde her owne mother and servantes in manner

and forme following ffirst she recommended her Soule and her conscience to our Lord Jesu and all the holy company

of hevyn and her hert and love to her said husband Richard Gading desiring hym to burye her bodye by

her ij children mary and Jane and all her goodes she holy gave and bequeithed to hir said husband Richard

Gooding right hertily wisshyng that it were moche more requyering her said husband whom she maide her

[new page]

executor he to delyver to her good mother as a legacie bequeathed by her Sex pound thyrtene shilling and foure pence

Itm she bequeathed to her said mother a pounced pece of Silver Itm she bequeithed to her said mother her Gowne ffurryd with

Calaber and her best kirtill of worsted Itm she bequethed to her Doughter fflorence her fyrst weddyng Ryng and her

littell flagon Cheyne of gold Itm she bequeithed to her Doughter Margerye her second weddyng Ryng beseching her said

husband Richard Goodding to be good to them her children and not to lett them come in other Strannge kepyng if he could

conveniently hold them Itm she bequeathed to her little son Erasmus Gadding (who was then nulye weynyd and furthe at

nurse) her Cheyne of gold that she was wont to weyre for a girdyll with all her joie and comfort beseching god to send

hym and his ij Systers grace and good fortune Itm she bequeithed to mother myfyn otherwise callyd mother wyfyn

a vale and a Rybyn Itm to Elizabeth Johnson a vale and a Rybyn Itm to Elyn Kayne a vale and a Rybyn Itm to

Mestres Toxton a paire of beides Itm to mother Bates the mydwif a vale and Rybyn Itm to yong Cotes his wieff

a vale and a Rybyn at Tosce the day and yere above sett These honest wemen which be legatrices in this present

Testament been also witnesses therof with diverse other

[1] TNA PROB 11/28/153, Will of Margery Gadyng, Wife, 10 July 1540.

[2] Ralph Houlbrooke, Death, Religion, and the Family in England, 1480–1750, (Oxford, 2000), p.84.

[3] Amy Erickson, Women and Property in early modern England (Routledge, 1996), p.26.

[4] Oxford University Press. (n.d.). Bead, n. In Oxford English dictionary. Retrieved October 17, 2025, from https://doi.org/10.1093/OED/1184505669

[5] Oxford University Press. (n.d.). Ribbon, n. In Oxford English dictionary. Retrieved October 17, 2025, from https://doi.org/10.1093/OED/4604404848