Posted by e.m.vine@exeter.ac.uk

21 May 2024**This will was part of the inspiration for a Chris Hoban song! Read his lyrics at the end of the post.**

Emily Vine

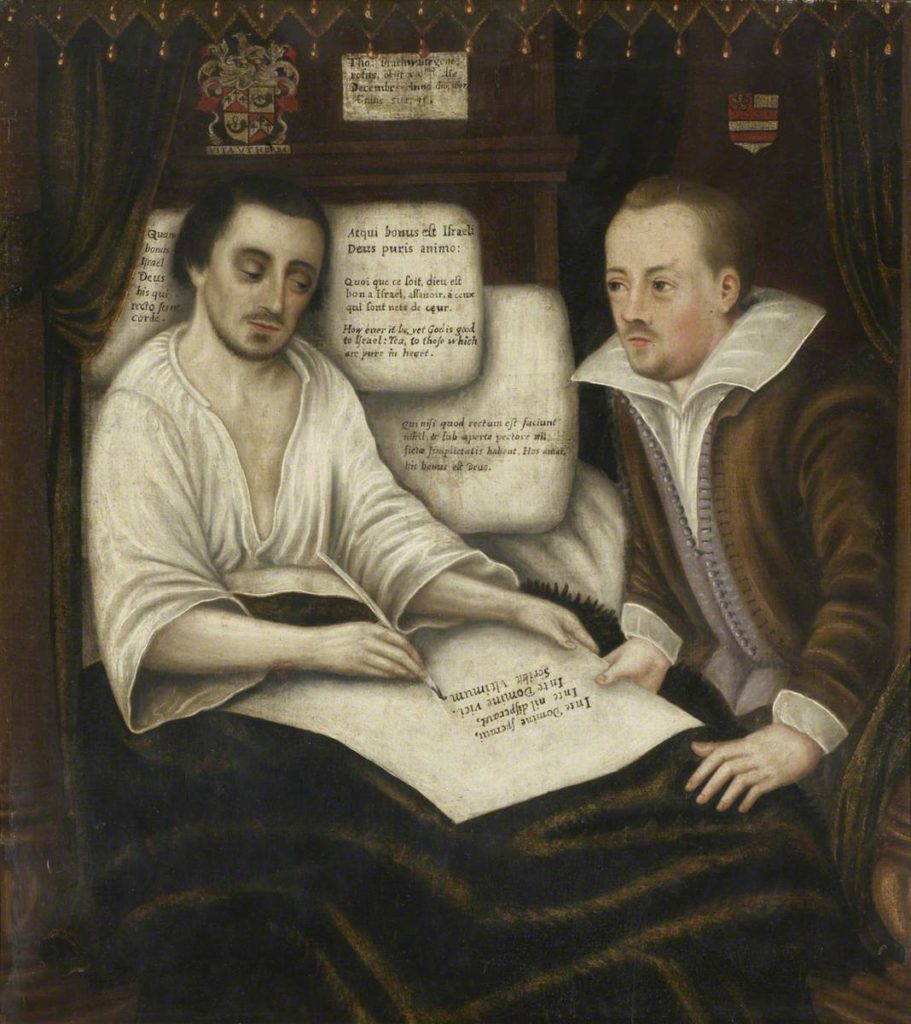

In this month’s post we explore the will of John Tylney, a man who had made his living from writing the wills of others. Tylney had lived and died in Bury St Edmunds, and when his will was proved in 1552, his profession was described as ‘Scrivener’: someone who wrote and copied legal documents, including last wills and testaments. Tylney’s will shows all the care and consideration of a man who had spent his life drafting such documents. As we will see, alongside the dispersal of possessions including gold rings, velvet night caps, and leather jerkins, Tylney also included an unusual but fitting final bequest.

Scriveners in Early Modern England

Keith Wrightson’s study of the Newcastle scrivener Ralph Tailor suggests that scriveners were increasingly necessary from the mid sixteenth century, with the expansion of the commercial economy, and the need for trades and transactions to be underpinned by formally written documents. Craftsmen and tradesmen may not have had the literacy, legal knowledge, or time to draft such documents, and would accordingly employ the services of a scrivener.[1]

People like John Tylney would therefore have been much in demand in regional centres such as Bury St Edmunds. Indeed, his own methodical will shows a deep familiarity with the genre and reflects a desire to do everything by the book: to account for all his worldly possessions, and to leave no legal ambiguities.[2] The will accordingly begins with Tylney confirming that he was ‘Renownsinge and Revoking all other willes and testaments heretofore made by me eyther by wryting or nuncupative’. This signals Tylney’s confirmation that this document was to be taken as his final will, and also acknowledges different forms of written and nuncupative (oral) wills. Nuncupative wills were formally recognised, but often made by those who were mortally wounded or likely to die quickly or unexpectedly, and who needed to hastily make their final wishes known.

Tylney’s will

Tylney ostensibly had a longer period of time to set his affairs in order: the will was proved after his death at the beginning of October 1552, but it had been written two months earlier on the 10th of August. As was very common at the time he appointed his wife ‘Cicelye’ as his sole executrix, which made her responsible for settling his debts and fulfilling the contents of the will. He also appointed John Howe as supervisor, he was tasked with assisting Cicely in implementing the terms of the will, and was given three pounds ‘for his paynes’.

Many of the bequests made in the main body of the will follow a fairly standard pattern and are reflective both of Tylney’s profession and local standing. On the day of his burial, he asked that six pounds be distributed ‘amonge the poore people in Bury aforesaide’. The provision of funeral doles – the dispersal of money to the poor of the parish or town – continued to be popular after the Reformation, even as some stricter Protestants expressed concern about the link between this form of charitable giving and prayers for the deceased. As David Cressy has suggested, the local poor ‘defined themselves by their willingness to accept’ these charitable provisions, which could include the dispersal of food as well as money.[3] So too could testators define themselves as being of certain status in their provision of these doles. This charitable bequest solidifies Tylney’s place amongst the established middling or professional class, indicating a scrivener’s relative standing within Bury St Edmunds.

Material Culture

Many of the material possessions listed in Tylney’s will were items of clothing and jewellery. He left to his brother, Nicholas Tylney, ‘my gown furred with black lambe’, my ‘doublet of lether’, and ‘my seconde payre of hoses’. Black lambs’ fur was a cheaper alternative to the use of ermine tails or sable as a fur trimming to clothing, and was often used by those who aspired to more fashionable or expensive styles. It also appears in the wills of other upper or established middling East Anglian men, including a Norwich Alderman who died thirty years before Tylney, who also bequeathed gowns trimmed with mink and black lamb.[4] The description of this item perhaps indicates that Tylney’s black lamb fur gown was prized by him; equally the description may also have been a means of ensuring that the correct item of clothing was identified amongst his possessions and given to his brother.

Tylney’s brother was to receive only his ‘seconde payre of hoses’, whereas John Howe, the aforementioned supervisor of the will, was to receive his ‘best peyre of hoses’, along with his ‘best doublet’, his ‘best felt hatte’, his ‘night cappe of velvet’ and his ‘Jerkyn of Chamlet’. John Howe’s wife, Elizabeth, and his widowed mother, Agnes, were also left ‘one golde ringe’ each. In the absence of further detail, we can only speculate as to why Tylney’s brother received only the second-best doublet and jerkin, whilst John Howe got the best, or why Howe’s female relatives were left some of the most valuable items listed. It is possible that Tylney had a closer kinship connection to the Howe family than can be discerned from the will alone. In a methodical will such as Tylney’s, such decisions were carefully thought out, and point to both the different values attributed to different personal possessions, the differing relationships between testator and beneficiary, and the debts owed to those who assisted in the process of executing a will.

The clearest example of the latter is Tylney’s unusual final bequest. He left ‘to Nicholas Legg the wryter hereof all and singular my presidentes and books’. Legg was a fellow scrivener of Bury St Edmunds, and evidently he was also the man who penned Tylney’s will. Tylney’s bequest was presumably in recognition of the work taken to write up the document. As is common with bequests of this nature, we don’t know how many books this legacy comprised, or their titles and contents, but we can presume that many of these texts were related to their shared line of work. The reference to ‘presidentes’ likely denotes legal precedents, another allusion to their trade. In a similar vein it was common for clergy for example to leave bequests of theological texts to other men of the church (for one example of this, see one of our earlier ‘Will of the Month’ posts). John Craig has noted that bequests of books and papers between fellow scriveners exemplified the close associations and local networks within this profession. Indeed, Nicholas Legg’s own daughter, Margaret Spitlehouse, would go on to work as a scrivener of Bury St Edmunds in her own right – one of few female scriveners working at this time.[5]

John Tylney’s will therefore exemplifies the life of a man who had valued professional associates, who was deeply integrated within the life of his local town of Bury St Edmunds, and whose work as a scrivener led him to be deeply methodical in the dispersal of his own worldly goods. It is also poignant to think about the mutual professional respect between John Tylney and his fellow scriveners like Nicholas Legg: men (and women) who ostensibly spent their days writing the wills of others, and who were occasionally called to perform that same final obligation for one of their own.

[1] Keith Wrightson, Ralph Tailor’s Summer: A Scrivener, His City and the Plague, (Yale University Press, 2011), pp.66-67.

[2] PROB 11/35/311 3, Will of John Tylney, Scrivener of Bury Saint Edmunds, Suffolk, 3 October 1552.

[3] David Cressy, Birth, Marriage, And Death: Ritual, Religion, and the Life-Cycle in Tudor and Stuart England, (Oxford University Press, 1997), p.444.

[4] Elspeth M. Veale, ‘VII. Fashions in Fur’, in The English Fur Trade in the Later Middle Ages, (London, 2003) pp. 133-155. British History Online https://www.british-history.ac.uk/london-record-soc/vol38/pp133-155 [accessed 16 May 2024].

[5] John Craig, ‘Notes and Queries: Margaret Spitlehouse, Female Scrivener’, Local Population Studies 46 (1991) p.56 http://www.localpopulationstudies.org.uk/PDF/LPS46/LPS46_1991_54-57.pdf

Will of John Tylney, Scrivener of Bury Saint Edmunds, Suffolk, 3 October 1552, PROB 11/35/311

In the name of God Amen The tenthe daye of August in

the yere of our Lorde god a Thousande five hundreth fiftie and two And in

the Sixte yere of the Reigne of our moste noble and deare Soveraigne Lorde

Edwarde the Sixte by the grace of god of Englande fraunce and Irelande Kinge

defender of the Faythe and in earthe under christ supreme hedd of the churche of

Englande and Irelande. I John Tylney of Bury St Edmund in the Countie

of Sufk and in the dioces of Norwiche Scryvener being of good mynde and pfytt

Remembrance at Bury foresaide the daye and yere above written make & ordeyn

this my present testament and laste will. Renownsinge and Revoking all other

willes and testamentes heretofore made by me eyther by wryting or nuncupative

willing that no persone or persones shall take any maner advantage or profytt

by reason of them or any of them but this firmely to stande as my present testament

and last will ffirst I comende my soule to Almyghtie god my Creator Redemer

and Saviour and my bodye to the earthe where yt shall please god to calle me

unto his mercie. Item I will have distributed and dealte at the daye of my

buryall amonge the poore people in Bury aforesaide Sixe poundes. Item I give

and bequeathe to Cicelye my wife my mesuage whiche I dwell in with the

Country thereunto adjoyning holly as I purchased yt set and lying in the churche

gate streate in the parishe of Seynt Mary in Bury foresaide, and my house

garden sett and lying in the west gate streate of the saide towne To have and

to holde all the saide mesuage Tennentry howses and garden to the saide Cicelye

her heyres and assignes forever Executed and Resigned to Nicholas Tylney my

Brother the said Tenentry to my saide Mesuage adjoynyng in the churche gate

strete with all comodities and easements as he hath and occupieth yt at this presente

daye among his lyfe natural And after his decease I will the said tenentry

holy remayne unto the said Cicely my wief withoute any disturbannce. Item I

give and bequeathe to the saide Nicholas Tylney my brother Twelve poundes

of lawfull money of England to be payde to hym his Executours or Assignes

by myn Executrix here under named her Exectors Administrators or assignes

in forme following. That is to saye witin the space and terme and space of one moneth next

after my decease fourtie shillinges, And witin the terme and space of one half

yere then next and ymediately entrynge other fourtie shillinges and so furnishe

every half yere and ymediately following another fourtie shillines untill the

said somme of Twelve poundes be fully contented and paide, Item I give & bequeathe

to the saide Nicholas my gowne furred with black lambe my doublet of lether my white peticot my Jerkin of Lether

My Buffet As to my seconde payre of hoses and my buttened cappe / Item I

[New page]

gyve and bequeathe every one of the Children of John Howe of Stowemarket

Clothier being alive at this presente daye twentye shillinges, Item I give & bequeathe

to Richarde Grene Shrinte with the saide John Howe three poundes of lawfull

money of Englande to be paide to the saide Richarde by my saide Executrixes

her Executors Administrators or assignes when he shall atteyne and come to the

Age of xxi yeres And yf it fortune the saide Richarde to decease at any tyme

within the said terme of xxi yeres then I will the saide three poundes remayne

to Cicely my wief, Item I give and bequeathe to Alice Grene sister to the said

Richarde twentie shillinges to be payde to her at the discrecion of my said Executrix

Item I give and bequeathe to the said John Howe my best doublet my Jerkyn

of Chamlet my best peyre of hoses. My best felt hatt my Redd peticote and

my night capp of velvet Item I give and bequeathe to Elizabeth wief of

the saide John Howe one golde Ringe, And to Agnes Howe wydowe mother of

the saide John one golde Ringe, And I give and bequeath to every one of my

godchildren being alyve at my decease xijd, Item I give and bequeathe to

Nicholas Legg the wryter hereof all and singular my presidentes and bookes

The residue of all my goodes and Cattalls Implementes Jewelles and Stuff

of howshold moveable and unmoveable of what name or nature soever they be

with all my debtes to me due or hereafter to be due I give and bequeathe to the

said Cicely my wief whiche saide Cicely of this my present testament and Last

will. I constitute ordeyne and make my sole and only Executrix, she to

paye my debtes performe and fulfill this my present testament and last will

and bring me honestly to the perthe, And I constitute and ordeyne of this

my present testament and laste will the saide John Howe Supervisor giving

to hym for his paynes taking and ayd to my said Executrix three poundes

In witness hereof I the saide John Tylney to this my present testament and last

will I have put my seale the daye and yere first above wryten. Thes witness

Thomas Gyppes Thomas Cage clothier John Bright Maulster and Nicholas

Legg per me Johan Tyleney by me Thomas gyppes Testente Nichol Legg.

And so imprimis

In the name of God Amen

Then the preamble

I’ll just get another pen

And then the main bequests

But our time is running out

He is on the point of death

And there are people all about

His elder brother

He’s the one with all the wealth

And then his servant

He’s not feeling great himself

And then his lawyer

Who has an overweening pride

With more caveats than anyone

Could ever hide inside

Everyone repeats each word he says

His breath is shallow, his thoughts are vague

Oh, who would be a scrivener

In the time of plague?

So at the first stroke

I’ve another will to write

And at the second stroke

Oh, we could be here all night

And at the third stroke

If none of this should come to pass

I will leave it to the brother

Of the one before the last

Outside the window

I barely hear what he has said

With every echo

For all I know, he could be dead

And then the lawyer

Tries to justify his fees

By hitting me with paragraphs

Of turgid legalese

While annotating

Every change of mind he makes

His voice is fading

With the length of time it takes

To set his thoughts down

But before the ink has dried

Someone shouts along the alley

That his next of kin has died

The air is thick, and I can hardly think

In the confusion his father walks in

I say ‘We’re nearly finished’

Then he says ‘Let us begin’

And so imprimis

In the name of God Amen

Then the preamble

Must I write it out again?

And then the main bequests

But he is looking so perplexed

With everyone around him thinking

…“I could be next”

So at the first stroke

I’ve another will to write

And at the second stroke

Oh, we could be here all night

And at the third stroke

If none of this should come to pass

I will leave it to the brother

Of the one before the last

…Or the sister of the one before the last

…Just remind me, who’s THE ONE BEFORE THE LAST?

Postscript: the original idea for this song came from Keith Wrightson’s book, Ralph Tailor’s Summer: A Scrivener, His City and the Plague (Yale University Press, 2011), which focuses on the activities of a scribe in Newcastle-Upon-Tyne in 1636, a plague year. Chris writes: ‘the idea also came from Emily’s blog post – not so much in its detail but in imagining, through the post and some of the intricate details of his belongings and surroundings, what a scrivener’s life might have been like (something we really don’t know much about with regards to Ralph)’.