Posted by e.m.vine@exeter.ac.uk

25 September 2025Dylan Cox

Dylan is a third year History student at the University of Exeter who has been on a work experience placement with the ‘Material Wills’ project over the summer. Dylan has transcribed and researched the will of a London gentleman, and in this blog post he reflects on what the will can tell us about seventeenth-century society, on different ‘styles’ of will-making, and also on the process of this type of archival research more broadly.

This month’s blog post discusses the will of Giles Rawlins, proved on the 10th of June 1678, in which he describes himself as a ‘London Gentleman’.[1] What stood out to me about this will was that it offered a unique approach toward will making, one in which finances dominate as Rawlins’ discussion of his ‘Temporall Estate’ lacks mention of many of the sentimental objects and funerary arrangements that form the focal point of many other wills. Instead, a concern with distributing money, settling debts, and allocating property form the bulk of the content. This highlights the testator’s pragmatism and concern with settling his estate. Rawlins states that he is ‘Revoaking all wills by me formerly made’. This suggests that he made several versions of his will, and that the desire to settle his financial affairs was a constant concern in the final years of his life. A potential reason for this style of will-making could be that Giles preferred to give during his life, opting to allocate those possessions most sentimental and valuable outside of his will. If this was the case it highlights the variety of attitudes toward gift-giving and will-making: some saw it as an opportunity to list and divide up their personal effects, while others made alternative and often undocumented arrangements for their possessions.

The challenges of archival research

The will is a good lesson in the perils of archival research, for if I had been specifically searching for a particular Giles Rawlins, I would have encountered some difficulties. When trying to find out more about this testator, I have found records of two different men named Giles Rawlins, who both had their wills proved in the Prerogative Court of Canterbury in 1678, and who both had ties to Hereford. This adds an additional layer of difficulty when trying to identify testators and piece together an accurate picture of their lives. Nevertheless, one of the two men named Giles Rawlins was born in Herefordshire and lived from 1601 to 1678, a place familiar to the testator of this will as he left ‘the Poore of the Parish of Langarron in the County of Hereford the sum[m]e of Tenƒn pounds’.[2] Moreover, he owned both Birley Court and land in Hereford. This Giles Rawlins attended Oxford University and graduated with a BA in 1622 and a MA in 1625, he was also the Rector of Ganarew in 1624 and Wolferlow in 1625.[3] If this Giles Rawlins is the ‘London Gentleman’ of this will and of this blog, then he would have been educated, wealthy, and an individual who moved to London later in life. However, the educated man involved in the church could very well be identified as the alternative Giles Rawlins, whose will reveals he was the ‘Clerk of Highley’.[4] This is only further confused by the fact we know the ‘London Gentleman’ made at least one other will prior to the one discussed in this blog post. Such difficulties are the product of historical sources created without concern for the logistics of research centuries later, rather, they were legal documents which served a purpose at the time, a fact exemplified by this will’s pragmatism.

A window into Early Modern London

This Giles Rawlins lived in London and mentioned his ‘dwelling house in fryday streete’: this may have been his primary residence as the letters of Sir Roger Hill from October 1677 address a Giles Rawlins of Friday Street. However, this property may have also been ‘knowne by the name of the signe of the Rose and Pomgranett’, likely an inn, which reveals interesting information about London in the late seventeenth century. Using ‘John Stow’s A Survey of London’ we find that Friday Street was “so called of fishmongers dwelling there, and seruing Frydayes market” and was situated in an area of considerable wealth as “tall houses, of three or foure stories in height,” were built. Furthermore, it lay next to “Bredstreete” which “is now wholy inhabited by rich Marchants” and “diuers faire Innes bee there, for good receipt of Carriers, and other trauellers to the city”.[5] Here, Stow mentioned the inns which housed travellers and provides an insight into the significant degree of wealth. This is corroborated by the fact that the adjacent parish churches of St. Matthew, St. John the Evangelist, and St. Margaret Moses housed the graves of 12 notable men, including John Mabbe the once Chamberlain of London.[6] By considering the property mentioned in Rawlins’ will, we can piece together a clearer view of the structure of London, and the geographic distribution of wealth.

Charitable bequests

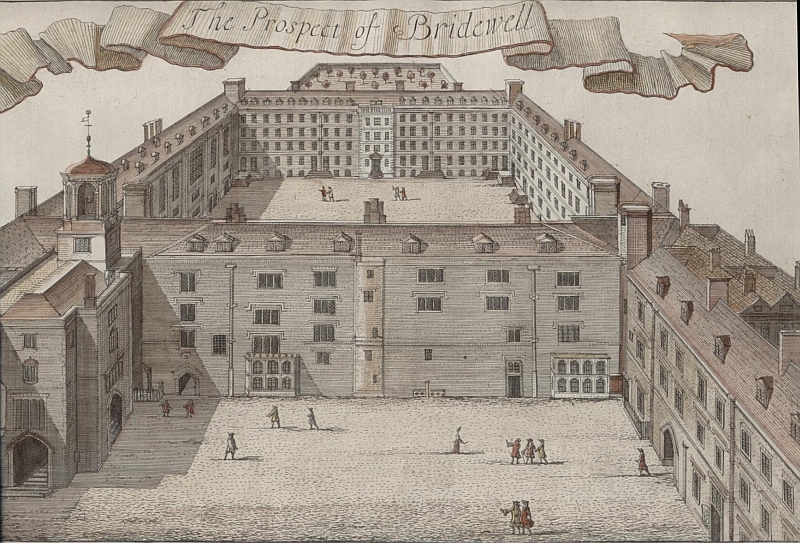

To be expected from an individual of considerable wealth, Rawlins made multiple charitable bequests, including ‘to the Hospitall of Bridewell the sum[m]e of ffive pounds’. [7] Bridewell Hospital, a charitable institution, was initially established as a royal palace in 1553, but was later used to punish ‘disorderly poor’ and house homeless children in London.[8] Furthermore, Bridewell hospital provided desirable apprenticeships known as ‘Lock’s Gift’, worth £10, that were used to provide a boy with a basic education and trade. In the late seventeenth century, there were 100 apprenticeships offered by the hospital. However, its dual function as a house of correction meant hard labour and whipping were used as modes of punishment acting as alternatives to incarceration. Bridewell was a large institution which housed a significant, transient, prisoner population which peaked in 1702 at 1474 individuals.[9] Therefore, Rawlins’ will reveals not only information pertaining to the wealthy of London, the merchants of Friday Street, but also those at the other end of the socio-economic scale.

A rare mention of sentimental possessions

Material possessions dominate many other wills, however, their near absence in Rawlins’ will highlights the diverse approach to will-making in the seventeenth century. Whereas some individuals spent time organising funerary arrangements and allocating precious objects, Giles Rawlins appears to use his will for its more utilitarian purpose, distributing wealth and paying debts. However, two of the few objects detailed are ‘Gold Ring[s] of Twenty shillings price’ which he ‘Bequeath[ed] To my Cozen William Gwyllim and his wife’, which were most likely mourning rings.[10] From the seventeenth to the nineteenth century, dedicating money in one’s will toward mourning rings was common practice and can provide insight into class dynamics in early modern England.[11] Jolene Zigarovich argues such rings were “sentimental, intimate, and personalised while also commodified, class-oriented, and public”.[12]

The 20 shillings Rawlins left for each ring would be worth around £113.78 as of 2017.[13] This figure appears to be an appropriate sum as Samuel Pepys similarly ordered 46 mourning rings at 20 shillings each in his will around the same era.[14] However, more extravagant options were available such as the “two hundred pounds for a ring” to each executor left by Horace Walpole the 4th Earl of Orford in 1797, which was closer to £15,000 each in 2017.[15] This invites questions surrounding the role played by wills to the importance of displays of wealth and class dynamics in Early Modern England. Overall, this will of a ‘London Gentleman’, and its focus on property and finance, allows a more defined vision of the reality of London life to be constructed beyond generic terms such as ‘rich Marchants’ and ‘fishmongers’ found in other sources.

Full Transcription of the Will of Giles Rawlins, Gentleman of City of London, 10 June 1678, PROB 11/357/59

I Giles Rawlins of The

Citty of London Gentleman being weake in body but of good and p[er]fect

memory (Thanks be to God) Doe make ordeine and declare this to bee

my last will and Testament in manner and forme following Revoaking

all wills by me formerly made And as for the setling of my Temporall

Estate I doe give and dispose thereof in manner and forme following

(That is to say) First I will that all those debts That I owe to any person or

persons whatsoever be well and truly Contented and paid within Convenient

time after my decease by my Executor hereafter named Item I order and

appoint to be bestowed upon my ffunerall the sum[m]e of One Hundred

pounds Item I give and bequeath to the Hospitall of Bridewell the sum[m]e of

ffive pounds Item I give devise and bequeath to the Poore of the Parish of

Langarran in the County of Hereford the sum[m]e of Tenn pounds Provided

that Six Hundred Pounds that I have in the East India Company come

safe home Item I give devise and bequeath to my brother Anthony Rawlins

the Sum[m]e of twenty pounds Item I give and bequeath to my Nephew

Thomas Rawlins my Brother Anthonyes sonne the sum[m]e of Tenn pounds

To be paid him within Two yeares after my decease Item I give and

Bequeath To my Cozen William Gwyllim and his wife each of them one

Gold Ring of Twenty shillings price Item I doe hereby declare and

appoint That all my Manno[r] or reputed Manno[r] of Burley als Birley

als Birley Court with the Rights members and appur[tennances] thereof in the

County of Hereford that I lately purchased of S[ir] Roger Hill in my owne

name and in the name of my Brother in Law Thomas Herbert And all and

singuler the Messuages Lands Tenements hereditaments and premisses

whatsoever thereunto belonging shall be setled and vested in the said

Thomas Herbert and my kinsman James Rawlins of the Citty of London

Gentleman their heires and Assignes In trust to the intent that they the

Said Thomas Herbert and James Rawlins and their heires may receive the

Rents and proffitts thereof for and vntill my sonne and heire Thomas

Shall or might attaine the age of one and Twenty yeares which said Rents

and proffitts that shall be made thereof during the said time is to be sett

out att Interest by them towards the Augmentation of the porcons of my

sonnes Giles and John Rawlins and my daughter hannah Rawlins to be

disposed among them in equall proportions And when my sonne Thomas

Rawlins shall attaine the age of One and Twenty yeares That the said Thomas

Herbert and James Rawlins and their heires doe Convey the same to the said

Thomas Rawlins his heires and assignes for ever But in in Case the said

Thomas Rawlins dye before he shall attaine the said age Then I direct

the said Lands and premises to be Conveyed to my sonne Giles or John

which of them shall first attaine the age of one and twenty yeares In

which case my meaning is that saith sonne as shall be entitled to the

said Mannor as aforesaid shall not have any of the moneys to be raised

in the meane time But the same to be equally devided amongst the rest

of my Children Item I give devise and bequeath my dwelling house in

ffryday streete in the said Citty of London with the appurtenances Comonly

called or knowne bt the name of the signe of the Rose and Pomgranett

unto the said Thomas Herbert and James Rawlins and the heires

To have and to hold to them the said Thomas Herbert and James Rawlins

their heires and assignes forever The which said house given and bequeathed

as aforesaid I doe bereby bequeath to the intent and purpose that with

what convenient speed may be after my death They the said Thomas Herbert

and James Rawlins doe sell and dispose of the same and for the most

that may be made and raised for the same And with that money and other

moneys To be raised out of the Third part of my personall Estate to pay S[ir]

Roger Hill One Thousand pounds with Interest that I as yet owe him of the

purchase money for the Mannor of Burleys aforesaid Item whereas

by the Custome of the Citty of London One Third part of my personall Estate

is att my owne disposall I doe hereby give devise and bequeath all of it

Except soe much as will be wanting vpon the sale of my house in

ffriday streete to make up One Thousand pounds due as aforesaid to S[ir]

Roger Hill vnto my said sonnes Giles and John and my daughter Hannah

equally to be devided between them when they shall attaine their severall

ages of Twenty one years And in the meane time to be sett out for their

best advantage And if either of them depart this life before he or she

shall attaine the age of one and Twenty yeares then my will is That

his or her part be equally devided amongst the survivors Item for the

Ease of my Executo[r] hereafter named I desire and appoint my Loving

freind M[aster] Thomas Powell of the Citty of Hereford to assist my said Executo[r]

in the Letting of my Lands in the said County of Hereford And to receive the

Rents thereof soe long as my Executo[r] shall think fit And to pay all

the moneys soe by him to be received to my Executors And for his paines

and trouble therein I give and bequeath to him ffive pounds per Annum

To be paid him by my [said] Executo[r] out of the said Rents during the time he shall

continue in that Imployment Item I make the said Thomas Herbert

and James Rawlins executors of this my Last will And give and appoint

them Tenn pounds a peice to buy them mourning and ffive pounds a peece

Per Annum for their paines until they shall be discharged of their Execu=

torship by being secured to their content from all damages and charges

that shall happen to them by reason thereof by such of my [said] sonnes as

shall ffirst attaine the age of one and Twenty yeares In Witnesse whereof

I have hereunto sett my hand and seale The Eighth day of may in the

Thirtieth yeare of the Raigne of our soveraigne Lord Charles the Second

over England xiv Annoqe Dmi 1678 . / G. Rawlins./ Signed sealed

and published in the presence of And the words ( To be disposed among

them in equall porcons) between the ffowerteenth and ffifteenth lines

And the words (of their Executors) in the last line but Three interlined

before sealing and publishing hereof in the presence of Nat: Strange

Katherine Strange William Kippin Katherine Ampler her marke

Elizabeth Harrish her marke./

[1] PROB 11/357/59, Will of Giles Rawlins, Gentleman of the City of London, 10 June 1678.

[2] PROB 11/357/59, Will of Giles Rawlins, Gentleman of the City of London, 10 June 1678.

[3] Highley Initiative and High St. Mary’s Church. “Highley.” Accessed August 5, 2025. http://www.highley.org.uk/index.html

[4] PROB 11/356/542, Will of Giles Rawlins, Clerk of Highley, Shropshire, 15 May 1678.

[5] John Stow, A Survey of London. Reprinted From the Text of 1603. Edited by C L Kingsford (Oxford, 1908), British History Online, accessed August 12, 2025, https://www.british-history.ac.uk/no-series/survey-of-london-stow/1603.

[6] https://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/FRID1.htm

[7] PROB 11/357/59, Will of Giles Rawlins, Gentleman of the City of London, 10 June 1678.

[8] L.W. Cowie, “Bridewell.” History Today, May 5, 1973, History Today.

[9] London Lives 1690 to 1800 Crime, Poverty and Social Policy in the metropolis. “London Lives 1690 to 1800 Crime, Poverty and Social Policy in the metropolis” Accessed September 2, 2025. https://www.londonlives.org/static/Bridewell.jsp

[10] PROB 11/357/59, Will of Giles Rawlins, Gentleman of the City of London, 10 June 1678.

[11] Victoria and Albert Museum. “Collections.” Accessed August 5, 2025. https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O125929/mourning-ring-unknown/

[12] Jolene Zigarovich, Death and the Body in the Eighteenth-Century Novel, (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2023) https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv2hq0hnc.

[13] https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/currency-converter/#currency-result

[14] Jolene Zigarovich, Death and the Body in the Eighteenth-Century Novel, (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2023) https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv2hq0hnc.

[15] https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/currency-converter/#currency-result