The most innovative and rewarding aspect of the Wills Project is that the Team has worked alongside a huge community of volunteers to meet the challenge of transcribing 25,000 wills. Crowdsourcing the time and skills of the general public to co-create data has proven highly successful in scientific research, but it is relatively new to the Humanities. The Wills Project capitalises on the potential of Artificial Intelligence to amplify the value of our volunteers’ contributions and create a data sample that is very significantly larger than any study that uses hand-produced transcriptions alone.

Our Zooniverse volunteers were able to hone and improve their palaeography skills at the same time as making a contribution to the success of a cutting-edge research project. The video below is a speedy overview of how the Zooniverse site worked. The two stages of volunteer participation are explained more detail in the boxes below.

All our volunteers became part of a larger research community with a common purpose and interest. The Project Team provided volunteers with regular updates on how the transcription and analysis was progressing, and we organised other events to raise awareness and excitement about the work.

‘Stage 1’ has now drawn to a close. During this stage we recruited a team of Expert Volunteers who spent the spring of 2024 transcribing a set of specially commissioned high-resolution photographs of sample pages from wills made between 1540 and 1790.

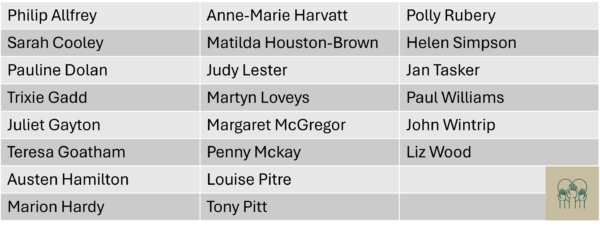

At the time of writing our team of Expert Volunteers have transcribed 414 pages of wills, consisting of 26,199 lines of text. This is an enormous achievement and a significant milestone in the progress of our project. We would like to offer a very warm thank you to each of our Expert Volunteers for all of their work:

The expert transcriptions produced by these volunteers form the ‘ground truth’ that we used to ‘teach’ or ‘train’ a Handwritten Text Recognition (HTR) model which can transcribe wills automatically. The next was to apply the model to our entire sample of wills, enabling us to auto-generate 25,000 will transcriptions.

VOLUNTEER ACTIVITIES

Our Early Modern Research Fellow, Emily Vine, worked closely with the volunteers during this period to familiarise contributors with the technology we are using, and our unusual transcription conventions.

Many of our volunteers transcribed directly onto and learned how to use the website ‘Transkribus’. They were also the first to see some of the early outputs of the Transkribus HTR model, and as part of this process, they checked and corrected a further 62 pages of HTR-generated text.

Emily and other members of the project team also answered queries on a dedicated online Forum and met with the volunteers in online workshops. The latter allowed us to introduce our experts to likeminded researchers, to troubleshoot transcribing problems, and to explain in more depth how the volunteers’ contributions fitted into our broader project aims and research questions. Many volunteers were also interested to learn more about HTR, and to consider its potential use in their own historical research.

We were delighted that some of the volunteers were also able to join us in person at one of two in-person ‘What’s in a Will?’ workshops at The National Archives and the University of Exeter in the summer of 2024. Not only did this give the project team the chance to meet them in person and to find out more about the volunteers interest in wills, it also meant that they were able to share their knowledge and experience of working with HTR with other workshop attendees.

The scale of our project is such that it would not be possible without volunteer involvement, but we intend that this co-creation of data is merely the starting point for broader dialogue with volunteers across the life of the project. So look out for some volunteer blog posts in the future, as well as more events and workshops.

Stage 2 ran on Zooniverse from October 2024 – October 2025. Click here to see our site.

The 25,000 will transcriptions generated by the Handwritten Text Recognition Software had to be checked carefully for accuracy and corrected where necessary. The more work that our volunteers put in, the more our technical experts, Mark Bell and Harry Smith, were able to fine tune and improve our HTR models. Fortunately the formulaic nature of wills (such as repetition of the term ‘Item I bequeath to’) meant that we could also auto-correct large parts of the text.

What we needed particular help with were the less common words or sentences in the wills – for instance the names of people and places; amounts of money and the items bequeathed. A great benefit of our process was therefore that our volunteers’ efforts were targeted at those parts of the wills that are most interesting to researchers.

Participants contributed to the project on the ‘Zooniverse’ crowdsourcing platform. There volunteers were shown images highlighting sentences from the will alongside the auto-generated transcription of the lines that they either verify, correct or transcribe.

The Zooniverse Community was able to access detailed instructions and advice and see transcription conventions in the same place. We also ran Talk Boards that allow volunteers to raise queries with the project team, or to chat with other volunteers about challenges or the interesting discoveries they made. We also engaged with our community by providing regular updates on progress, circulating newsletters, running webinars and holding an online and in-person ‘Transcribathon’ workshop where volunteers transcribed while learning more about the key research questions and initial indings of the project team.

Visit our Zooniverse site to see our results and view the chat boards.