Posted by Simon Barton

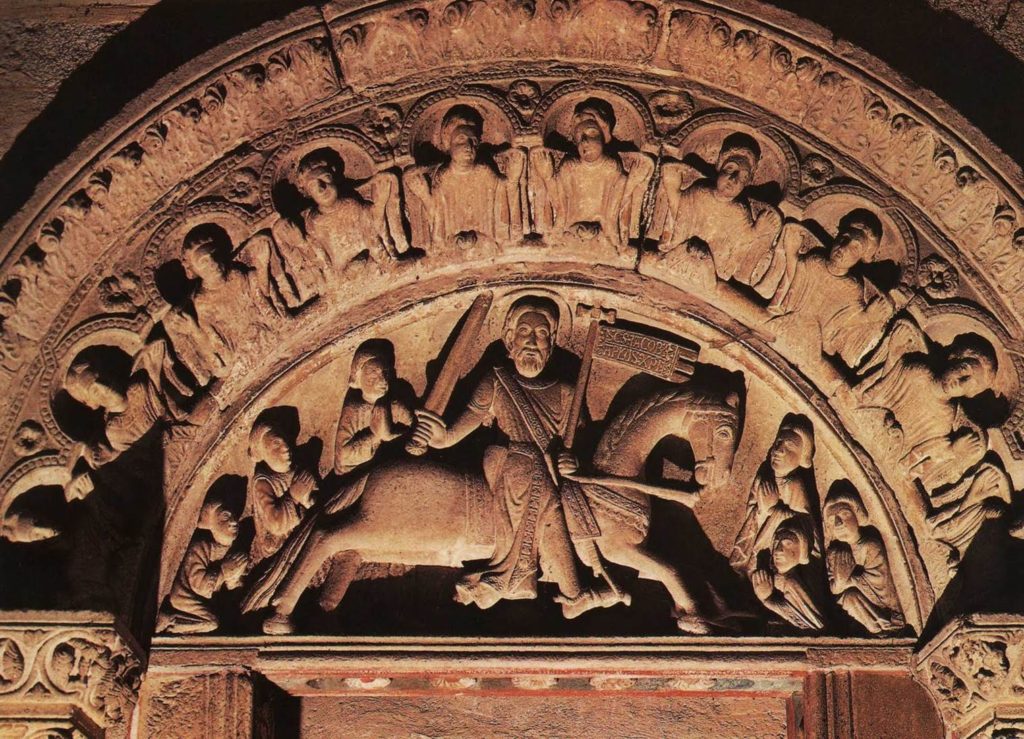

13 November 2014Every year, on the Sunday before 5 October, the feast day of St Froilán, the inhabitants of the Spanish city of León celebrate a popular festival known as Las Cantaderas. The fiesta, which has been in existence for almost 500 years, commemorates the decision supposedly taken in the late eighth century by the Christian kings of Asturias to deliver one hundred maidens to the emir of al-Andalus (Muslim Iberia) in annual payment of tribute. Tradition records that this obligation was later removed by King Ramiro I (842-50), who, with the miraculous assistance of St James, defeated a vast Muslim army at Clavijo in the Rioja in 844.

During the course of the Leonese festivities a group of young women dressed in medieval costume is instructed to dance by a figure known as the sotadera, who is to lead them southwards to join the emir’s harem. However, the sotadera takes the group on an alternative route as far as the cathedral, where further dancing takes place, Mass is held, and offerings are made to the Virgin to give thanks for the safe delivery of the women.

The legend of the tribute of the hundred maidens has gripped the imagination of Spaniards for the best part of 900 years and inspired an extraordinary outpouring of artistic creativity, including works of history, poetry, drama, painting and even a zarzuela (the Spanish opera form). The legend also lay at the heart of one of the most effective forgeries to have been carried out anywhere in the medieval Latin West: the solemn promise of an annual offering to the shrine of St James at Santiago de Compostela (the ‘Voto de Santiago’).

My latest research project has investigated the political and cultural significance of sexual encounters between Christians and Muslims in the Iberian Peninsula, from the Islamic conquest in the early eighth century to the end of Muslim rule in 1492. Examining a wide range of sources including legal documents, historical narratives, polemical and hagiographic works, poetry, music, and visual art, the book investigates the ways in which interfaith couplings were perceived, tolerated, or feared, depending upon the political and social contexts in which they occurred. In doing so, the book explores why the “cultural memory” of such liaisons carried such a powerful resonance within Christian society during the Later Middle Ages and beyond, and considers the part that memory played in reinforcing community identity and defining social and cultural boundaries between the faiths.

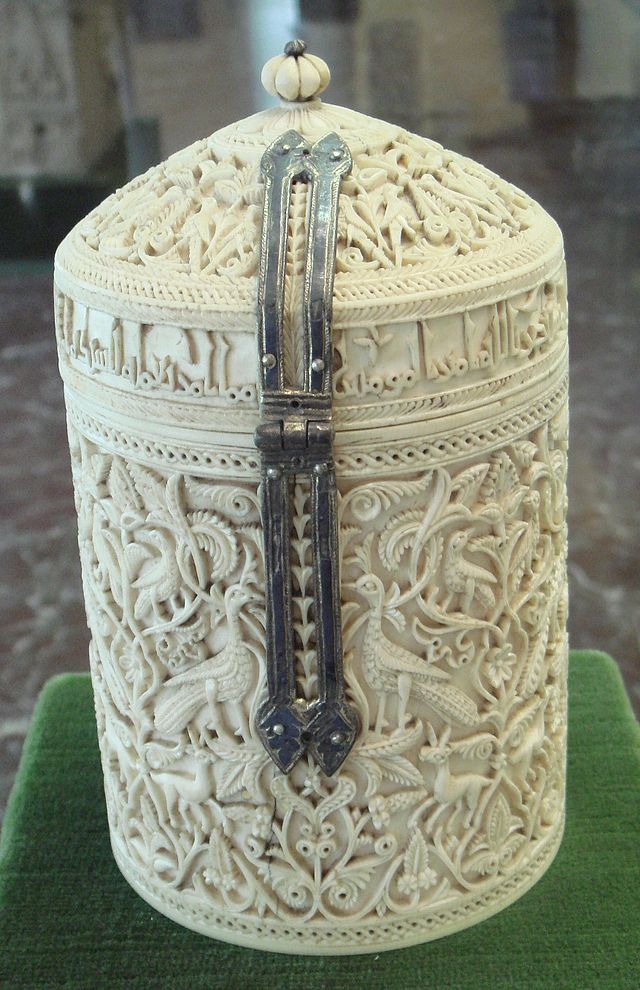

Marriages between Muslim men and Christian women helped consolidate Islamic authority over Iberia in the aftermath of the conquest. Marriage alliances were also a tool of diplomacy for the ruling Umayyad dynasty and for other elite Muslim families in their relations with the states of the Christian North. Meanwhile, procreating with slave concubines served as a dynastic defence mechanism, designed to ensure that a Muslim wife’s family would not stake its own claims to power. Furthermore, the enslavement of large numbers of Christian women during the course of Muslim attacks on the North, as a consequence of which some were recruited to the harems of the Muslim male élite, constituted a powerful weapon of war, designed to erode community cohesion on the Christian side and reduce its will to resist.

Yet attitudes towards such liaisons did not remain fixed throughout the medieval period. From the late eleventh century, a range of political, social and cultural forces – a shift in the balance of power in favour of the Christians; ecclesiastical reform; the influence of canon lawyers; and the development of a militant anti-Islamic ideology – converged to condemn interfaith marriage to swift decline. The Christian authorities also drafted laws that were designed to prevent sexual mixing between Christian women and Muslim and Jewish men.

For all their differences, Christian, Islamic and Jewish law codes were agreed that their own women should not indulge in sexual relationships with men of other faiths. The fear was that such liaisons would lead women to apostasy; but they were also viewed as acts of dishonour, both to the women and to their menfolk who had failed to protect them. By linking the sexual honour of a group’s women to the collective honour of the wider community, lawgivers and others imbued such sexual unions with intense political meaning. Yet interfaith sexual politics were asymmetrical. In al-Andalus Muslim men took Christian wives or concubines with the acquiescence of Islamic law; and while the Church authorities criticised those Christian men who took Muslim or Jewish concubines or frequented minority prostitutes, such relationships were not considered to undermine the existing hierarchies of power and were rarely punished.

The legend of the tribute of the hundred maidens, which first appeared c.1160, tapped into these anxieties. It also represented a warning from the past. Christians were reminded that military failure against the Muslims would not only be paid for with lives, lands and castles, but also with feminine sexual honour, which would in turn diminish the collective honour of Christendom as a whole. Christian soldiers therefore had to prove themselves as men, so that the memory of that past shame might be avenged and the barriers that had been erected between the faiths could never be breached again.

Conquerors, Brides, and Concubines: Interfaith Relations and Social Power in Medieval Iberia will be published by University of Pennsylvania Press in January 2015.