Posted by Teresa Tinsley

10 February 2015When Isabel of Castile and Fernando of Aragon took Granada from the Moors in 1492, their propaganda claimed it as a heroic victory marking the culmination of an 800 year struggle against Muslim invaders. Arabic and Jewish accounts, of course, reported it differently, but one Christian account is exceptional in presenting an alternative take on events. This was written – in Spanish – by Hernando de Baeza, a man who had been the Granadan emir’s interpreter and had lived with him in the Alhambra palace for the final four years of the Granada War.

Instead of presenting the Moors as enemies of the faith illegitimately occupying Christian lands, Baeza drew attention to the similarities and parallels between Christian and Moorish culture. For example, he explains sharia law as being like Christian canon and civil law. Baeza presents himself as a devout Christian but, in his narrative, Christians are not necessarily morally superior and Christian virtues are also displayed by Muslims. He also deals sensitively with the question of religious conversion and is strongly sympathetic towards Christians who, having been taken prisoner in Muslim territory, had converted to Islam and were regarded as apostates after Granada came under Christian rule.

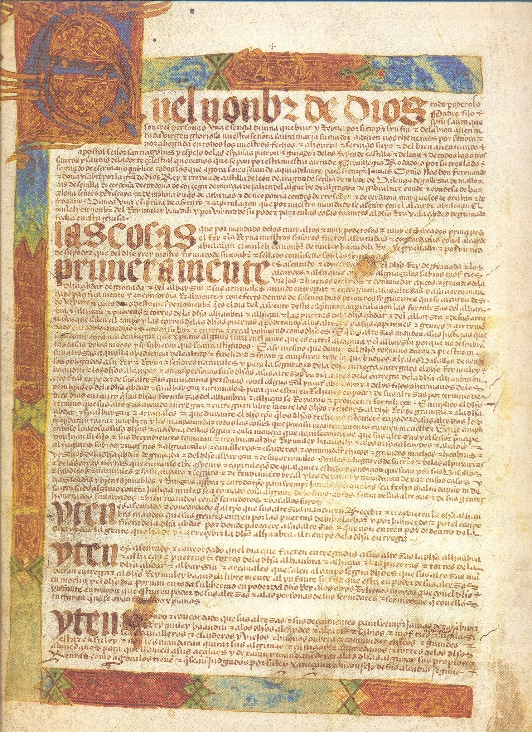

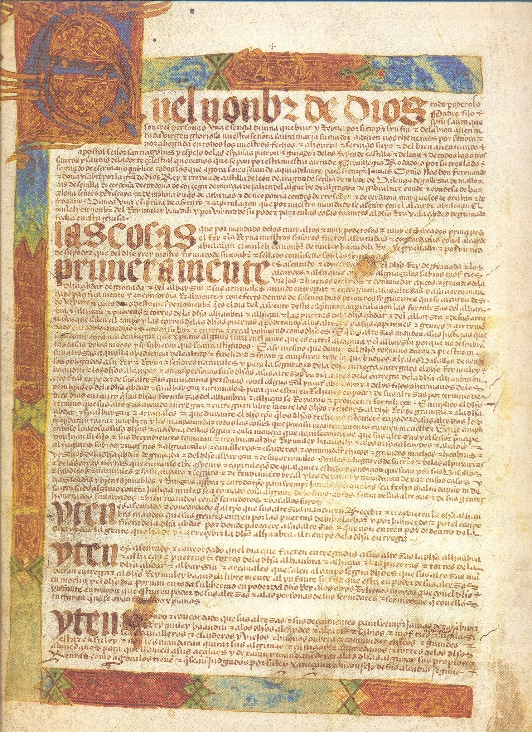

Baeza’s work was rediscovered in the 19th century and acclaimed as a fascinating narrative – it is full of beheadings, betrayals and daring escapades. In the 20th it was exploited as a useful source on events within the Muslim court in the period leading up to the Christian conquest. As Spain has rediscovered its multicultural past, the temptation has been to see Baeza as an early spokesman for liberal values representing the spirit of ‘convivencia’ in the ‘Spain of the Three Cultures’. But Baeza was writing at a crucial moment for the development of Spanish religious identity – around 1510 – and I read the text as a subtly subversive account confronting the most controversial issues of his day: tyranny versus social justice, the reform of the church, and the role of the Inquisition. Certainly, his readers understood these meanings, since a version of Baeza’s manuscript found its way into a mid-16th century codex compiled by Bishop Vasco de Quiroga on the conversion of Mexican Indians. Baeza’s account therefore deserves a more in-depth analysis, informed by an understanding of his background and positioning in the social and political context in which he wrote.

As part of my ongoing doctoral research I have so far explored two crucial aspects of his biography. Firstly, I have confirmed that he was of Jewish descent; his own parents and grandparents had been condemned to death by the Inquisition and he himself had been penanced for heresy. His case for a light touch approach towards apostates living in Granada therefore needs to be seen also as a personal, and at the same time more universal, plea for understanding in relation to the complexities of religious conversion.

Secondly, Baeza’s role in international affairs did not end with the handover of Granada. Between his time there and writing the piece, Baeza spent a number of years in Rome, in close association with Julius II, whom he helped to install as Pope, and other figures of the High Renaissance. I shall be arguing that it was here, in the light of the new currents of thought to which he was exposed, that he reflected on the more far-reaching aspects of the end of medieval multicultural Iberia and wrote, not just a simple memoire, but a more profound reflection on the future of Christianity in Spain’s emerging new global empire.

Teresa Tinsley, PhD Student