Posted by Levi Roach

27 February 2015This past month the Museum of Somerset in Taunton has enjoyed a particular honour: it has been host to the Alfred Jewel. Found in North Petherton (Somerset) by Sir Thomas Wroth in 1693, the Jewel was bequeathed the Ashmolean Museum in 1718 and has remained there ever since. Its homecoming (if the term may be used) has naturally been accompanied by much local interest and fanfare, including a feature to which I contributed on BBC Radio Somerset: the object was unveiled in a private viewing on the evening of January 30 in the presence of various notables and went on public display the following morning.

The Jewel itself is a small but intricately worked artefact about the size of a large necklace pendant. It consists of an enamelled plague set beneath rock-crystal and framed in gold-work which it ends in a small socket, suggesting that something once protruded out from it. The main figure in the middle of the jewel is thought to be Christ, though it is also possible that this represents ‘sight’. The quality of the craftsmanship alone would make the Jewel an object worthy of admiration, but the particular interest of this artetfact lies in the context of its production – it was apparently commissioned by no less a figure than Alfred the Great, that most famous of Anglo-Saxon rulers. On art-historical grounds alone the object can be dated to the second-half of the ninth century (i.e. Alfred’s time), but the key evidence comes from the inscription running along the edge, which reads AELFRED MEC HEHT GEWYRCAN, that is, ‘Alfred ordered me to be made’. Given the quality of workmanship, there can be little doubt that this ‘Alfred’ is none other than the ruling king of Wessex at the time (871–99).

Alfred’s biographer, the Welsh monk Asser, described his lord as a patron of arts and crafts and the Alfred Jewel can be placed alongside a number of other objects which have been associated with his court, including the Fuller Brooch and a series of similar jewels, including the

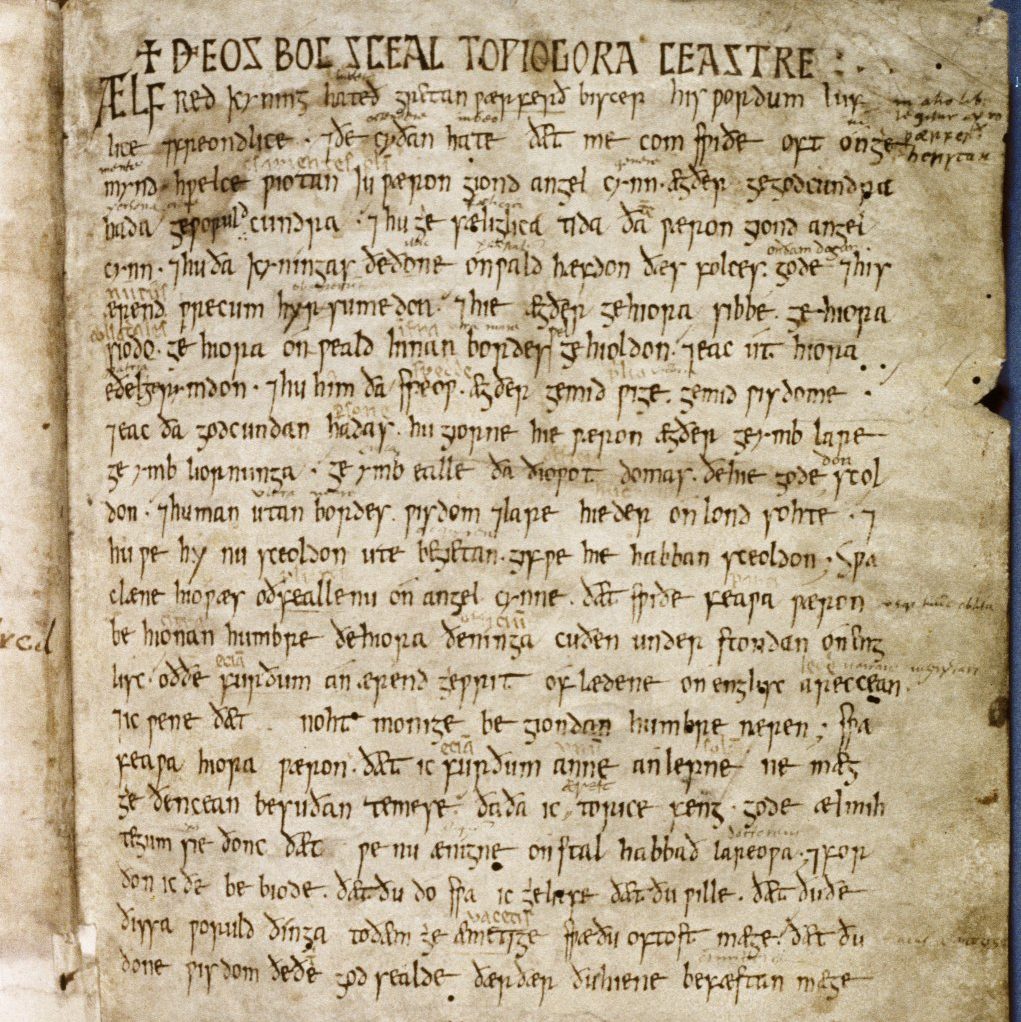

Minster Lovell Jewel, Warminster Jewel, Bowleaze Jewel and possibly three further items discovered in more recent years. However, though it may be in good company, there can be no doubt that the Alfred Jewel is the most sumptuous and significant of these artefacts. The precise function of the jewels is uncertain, but there is reason to believe that they may represent examples of what Alfred the Great referred to as æstels. Thus in the preface to his translation of Gregory the Great’s Pastoral Care, Alfred states that ‘I intend to send a copy [of this translation] to each bishopric in my kingdom; and in each copy there will be an æstel worth fifty mancuses’. The term æstel is otherwise unattested in Old English (it is a so-called hapax legomenon), but it clearly must have been something relating to reading (or books) and of substantial value (we know that estates could be sold for a mancus or two in this period). Given the small size and valuable nature of these objects, it has been proposed – plausibly, though not definitively, it must be emphasised – that they are versions of the enigmatic æstel mentioned in Alfred’s preface. If so, they would seem to have been not pendants, but pointers, intended as reading aids, and one imagines that they would have had impressive tips (perhaps of ivory) when first presented to their recipients.

With the rising number of such objects found in recent years, it may be that this traditional interpretation is ripe for revision, but no matter what historians, archaeologists and art-historians decide, one thing is certain: the Alfred Jewel will remain the prime example for an impressive type of ornament, produced and patronised by the court of one of England’s most famous and successful rulers, a king who made his last stand against the vikings at Edington with ‘all the men of Somerset’ (as the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle puts it). It is therefore only fitting that the Alfred Jewel should have been found in Somerset and has now found its way back ‘home’, however briefly.