Posted by Helen Birkett

17 October 2016On Friday night I attended a screening of the 1922 film Robin Hood at the Barbican Centre in London. In addition to bringing a silent cinema classic back to the big screen, the event also showcased Neil Brand’s rousing new score for the film, which was performed live by the BBC Symphony Orchestra. The new music is certainly an improvement on the soundtrack attached to the film on Youtube, however, as with most film scores, it is the visual spectacle rather than the music that stays with you.

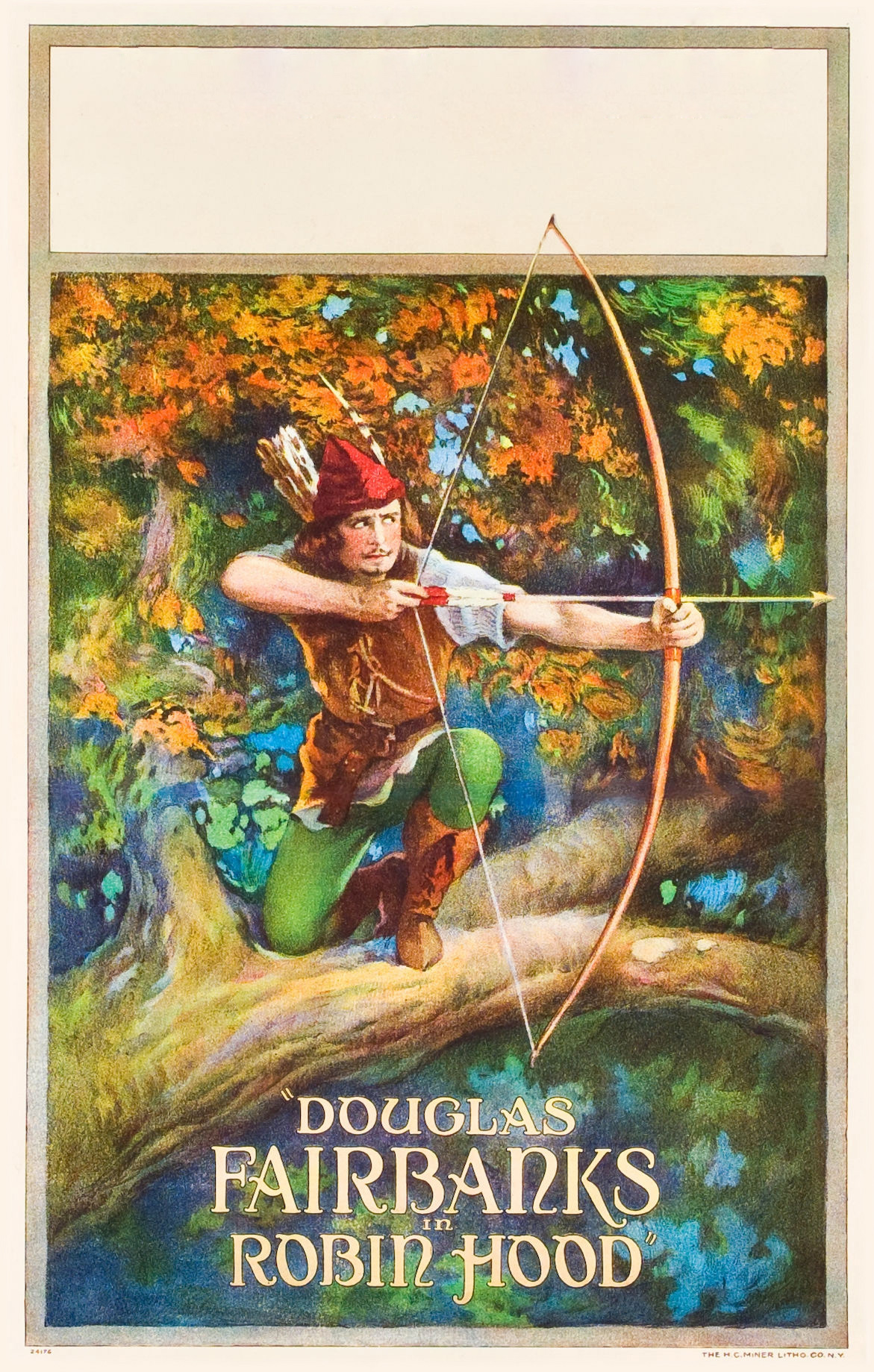

Robin Hood was one of the most expensive and extravagant films of its day. It was an unashamed vehicle for Douglas Fairbanks, as clearly indicated by the film’s official title: Douglas Fairbanks in Robin Hood. Fairbanks helped to adapt the story (he is credited under his middle names ‘Elton Thomas’) and gave himself, in effect, three roles to play: first, the Earl of Huntingdon, a virtuous, chain-mail clad knight; then his alter ego, Robin Hood, marked out by his hose, goatee beard, and bow and arrow; and, underlying both, the charming matinee idol version of himself. The latter is alluded to most obviously following his defeat of Guy of Gisbourne in the opening tournament, when it is revealed that the Earl of Huntingdon/Fairbanks is afraid of women. The physically imposing and jovial Richard the Lionheart, played with gusto by Wallace Beery, finds this hilarious – and encourages all the female spectators at the tournament to mob him. Poor Fairbanks is forced to dive into the moat to escape and, luckily, isn’t hindered by his stunt chainmail.

The pace of the film is somewhat surprising. The first hour and a quarter of the story is devoted to the initial set-up in which the Earl of Huntingdon falls in love with Marian, is wronged by Guy of Gisbourne, and then abandons the crusade to save England from Prince John’s tyranny. At this point, Robin Hood makes his first appearance and the final hour of the film gallops along at a much merrier pace: Robin’s outlaw band prance all over the screen as they save the oppressed people of England; Robin rescues Marian, brutally kills Guy (the new score includes a rather nasty crack as his spine snaps), is captured by John and saved from a Sebastian-like martyrdom by the arrival of King Richard. At the climax of the film, Robin and Marian marry – and poor Richard, who seems to think that, as their monarch and their chum, he is entitled to hang out with them on their wedding night, finds himself locked out of their chamber. There is much to raise the modern eyebrow in this film, not least the bromance of lingering looks between Robin Hood and Little John – particularly in contrast to the rather chaste and motherly relationship between Marian and Robin.

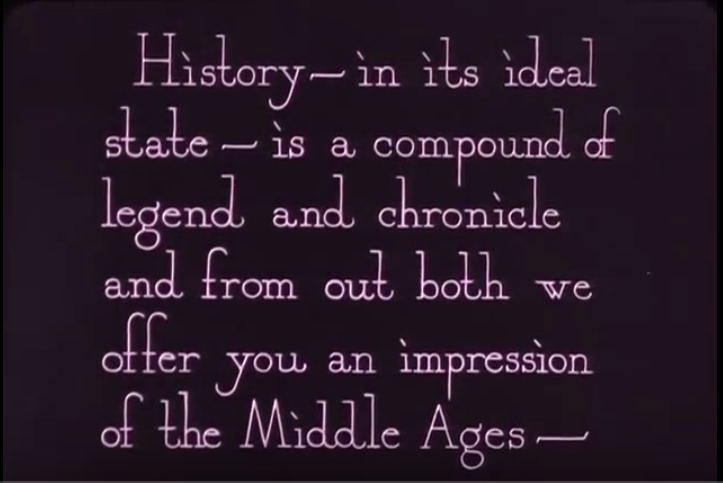

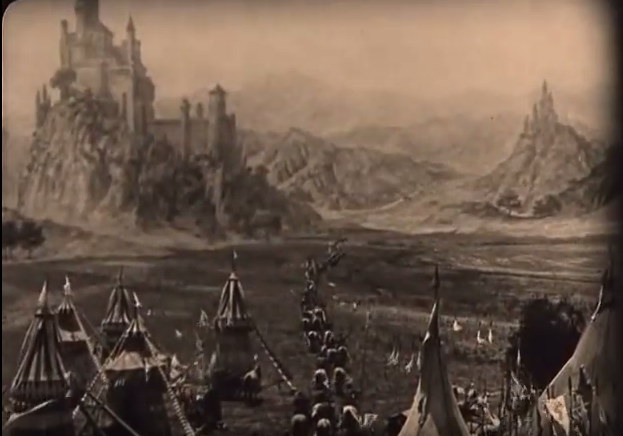

For the medievalist, there is also much to amuse. The films opens with the statement that ‘history – in its ideal state – is a compound of legend and chronicle’, which, while irking the purist, probably represents popular attitudes to medieval films both then and now. The same liberal approach is evident with regard to the sets. Robin Hood’s landscape draws on the extant architecture of the medieval past and the distorted structures of medieval illustration. When the camera follows Richard’s crusader army to France, the audience is presented with an open plain and turreted castles perched on rocky outcrops, which seem culled from later medieval manuscript imagery.

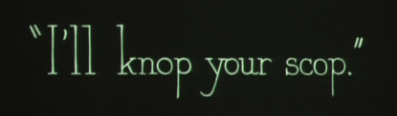

Back in England, Nottingham has been given similar treatment: it has the small, warped structures and large doorways of dwellings in manuscript-land. Finally, the cavernous inside of the royal castle mixes the height, space and light of a Gothic Cathedral with romanesque arches that could never have supported such a structure – and is quite different to the pokey palaces of medieval reality. This strange world also finds expression in the intertitles, which are deliberately archaized to the extent that they are sometimes a little difficult to understand on first reading. There is also a classic piece of medieval-sounding gibberish textually uttered by Friar Tuck as he prepares to test the fighting skills of a mysterious stranger:

Luckily, the context of the exchange gives meaning – “I’ll knock your block off” – to what are otherwise meaningless words (ah, the magic of cinema!).

So what did 1920s audiences want from Robin Hood and the Middle Ages? Well, above all, they wanted Fairbanks and they wanted him in an extravagant setting. Robin Hood was a high-end, lavish production that came hot on the heels of Fairbanks’ smash hits The Mark of Zorro (1920) and The Three Musketeers (1921). The film offered a suitably strange and archaic ‘impression of the Middle Ages’, which both accorded with audience expectations and provided Fairbanks with the fantastic backdrop needed for his latest swashbuckling epic.