Posted by Catherine Rider

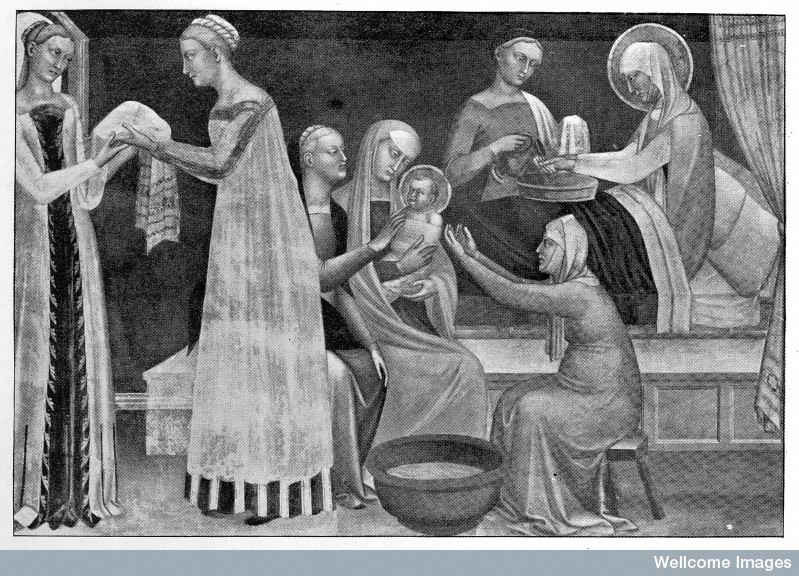

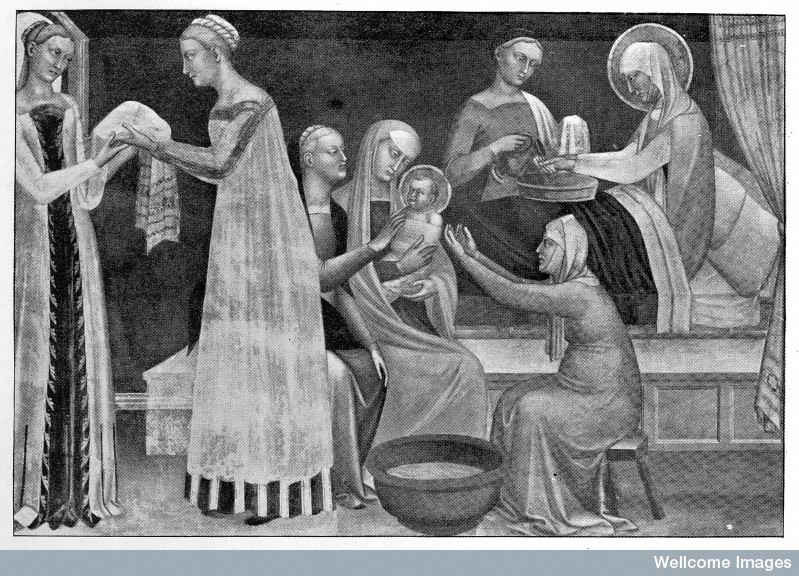

28 January 2017I’m on research leave this term and working on an ongoing project which looks at attitudes to infertility and childlessness in medieval England. Although there has been a great deal of work in recent decades on topics such as marriage, family structures, childhood and reproductive medicine in the Middle Ages (and in other periods) less attention has been paid to what happened if a married couple did not have children. This could have serious repercussions: children were often needed as heirs and as a means of support in old age, as well as wanted for the pleasure they brought. Not surprisingly, then, infertility is mentioned in a wide range of medieval sources. They include medical treatises and recipes which gave advice to help a woman to conceive or a man to beget a child, and which have received some attention from scholars such as Monica Green, as well as from me.[1] Less well studied are the religious texts which mention infertility, such as Bible commentaries, sermons, and saints’ lives. These works discussed a type of story that recurs several times in the Bible and in hagiography, when a previously infertile woman miraculously gives birth to a special child late in life. Women who fell into this category included the biblical Sarah, Rebecca and Rachel, as well as the apocryphal St Anne, mother of the Virgin Mary.

I’m currently in the process of picking up the threads of my research after a longish break and I’ve been thinking about the two questions that people ask me most often when I say I’m working on medieval infertilty.

This does seem often to have been the case, but things were not always that simple. The stories of miraculous children from the Bible onwards did tend to talk about women, specifically, as infertile. The medical texts were more nuanced. The widely copied twelfth-century medical compendium Trotula, for example, emphasized that could be impeded ‘as much by the fault of the man as by the fault of the woman,’ although it devoted more space to women’s infertility than men’s.[2] However, because we have so few records which describe the experiences of sick people in the Middle Ages it is difficult to know whether men or women were more likely to seek treatment for reproductive problems in practice.

I’m still working out exactly where the balance of attitudes lay, and how significant male infertility was thought to be.

Here the answer is complicated. Medical writers tended, unsurprisingly, to focus on the physical causes of infertility, such as imbalances of the humours or serious deformities in the reproductive organs. They may have believed that God was behind these physical problems but if so, they do not say so.

Rather more surprisingly, religious texts also shied away from presenting infertility as a judgement of God. Indeed, some writers went out of their way to say that this was not the case: the thirteenth-century compendium of saints’ lives, The Golden Legend, emphasized when it retold the story of the conception of the Virgin Mary that God might cause temporary infertility in order to allow a child to be born miraculously later on.[3] The fact that they emphasized this so strongly may suggest they were arguing against a common opinion – but it is hard to be sure.

*****

I’m still working out what all this means. What was the range of views and who held them? Which ideas were widely shared in the sources, and which were the unusual views held by only one or two writers? My plan over the next few months is to put together a journal article exploring the religious sources so I’m hoping to know more soon.

[1] See especially Monica Green, Making Women’s Medicine Masculine (Oxford, 2008); Catherine Rider, ‘Men and Infertility in Late Medieval English Medicine’, Social History of Medicine 29 (2016), 245-66.

[2] The Trotula: an English Translation of the Medieval Compendium of Women’s Medicine, trans. Monica Green (Philadelphia, 2002), p. 85.

[3] The Golden Legend, trans. W. G. Ryan (Princeton, 1993), vol. 2, p. 132.