Posted by Oliver Creighton

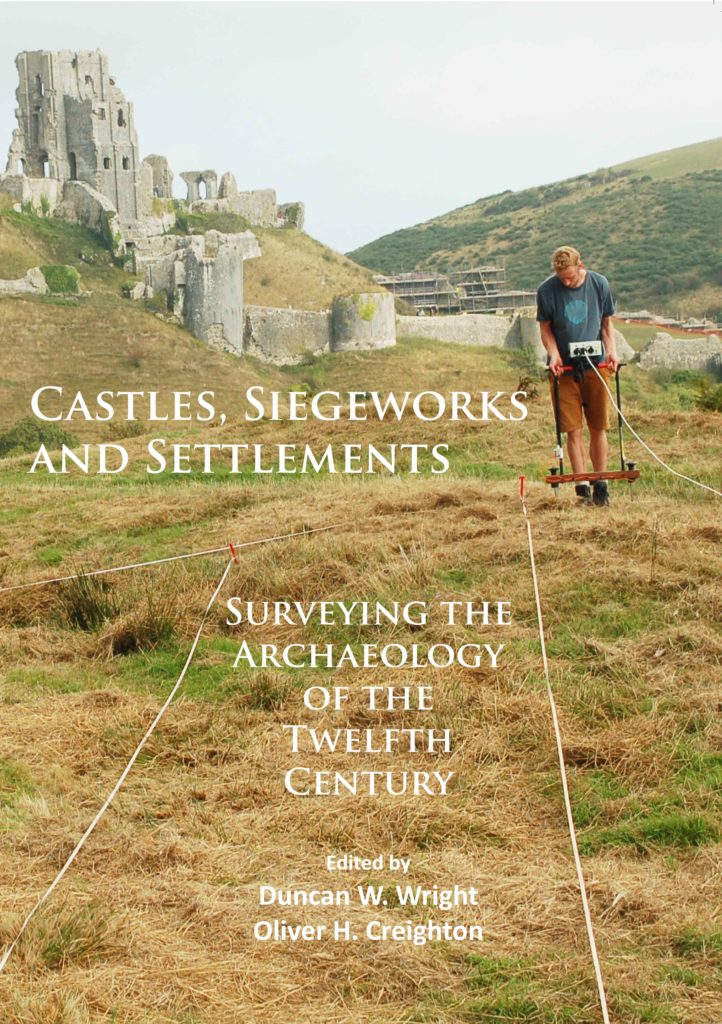

3 February 2017I’m delighted to see the fruits of a recent Exeter-based archaeological research project on the conflict landscapes of the 12th century published in book form. The co-written title Anarchy: War and Status in 12th-century Landscapes of Conflict, a volume of synthesis which is the principal output from the project, has just been published by Liverpool University Press, and a more specialist volume on archaeological surveys carried out during the fieldwork phase of the work is available through Archaeopress.

On the one hand it is a time to breathe a sigh of relief to see volumes that have seen such an investment of energy finally ‘out’. But the moment when fresh copies of your own books arrive on your desk it is also a time when a researcher will also reflect on the reasons for carrying out the work in the first place, ponder areas where the work headed off in directions that you didn’t quite anticipate, and think about future plans…

In this case, the research root of the work was an AHRC-funded project on the historic town and castle of Wallingford, which I had the pleasure to run with colleagues at the Universities of Leicester and Oxford, in partnership with local groups. While the main focus of this project was the evolution of a townscape from the late Saxon through to the post-medieval period, as the work developed we became increasingly aware of the place’s pivotal role in the civil war of King Stephen’s reign, in the 1130s, 40s and 50s. The place was the Angevins’ flagship castle for much of this infamously bitter conflict and resisted three protracted sieges, making it the most besieged place in England at the time. But relating the colourful accounts of these complex actions by chroniclers, involving numerous sieges, counter-sieges, raids and armed clashes, to the actual landscape of the town and its surroundings proved immensely challenging — no more so than in trying to locate the many ‘lost’ siege castles built around the town between 1139 and 1153.

My deepening curiosity about what archaeology could (and could not) tell us about this bleak but fascinating period and its ‘real’ impact on society and landscape led me to develop a project that would aim to marshal and interrogate the full range of available archaeological evidence, and conduct fresh fieldwork to explore on a range of sites. In terms of historical work on Stephen’s, there of course exists a vast historiography, with a raft of key volumes written and edited by towering figures of medieval history. In contrast, precious little had been written of the period’s archaeology.

With funding from the Leverhulme Trust, to whom we are hugely grateful, the two-year project saw a research team working in archives, record offices and of course in the field, where we carried out new surveys of a selection of sites — primarily castles, siege castles and settlements — across England. A characterising feature of the work was the way we investigated this conflict’s archaeology at a series of different scales — from analyses of individual artefacts (such as weaponry and dress accessories) to the physical remains of fortifications and their landscape settings, and through plotting datasets at regional and national scales, including the coinage, which tells us so much about shifting patterns of royal control.

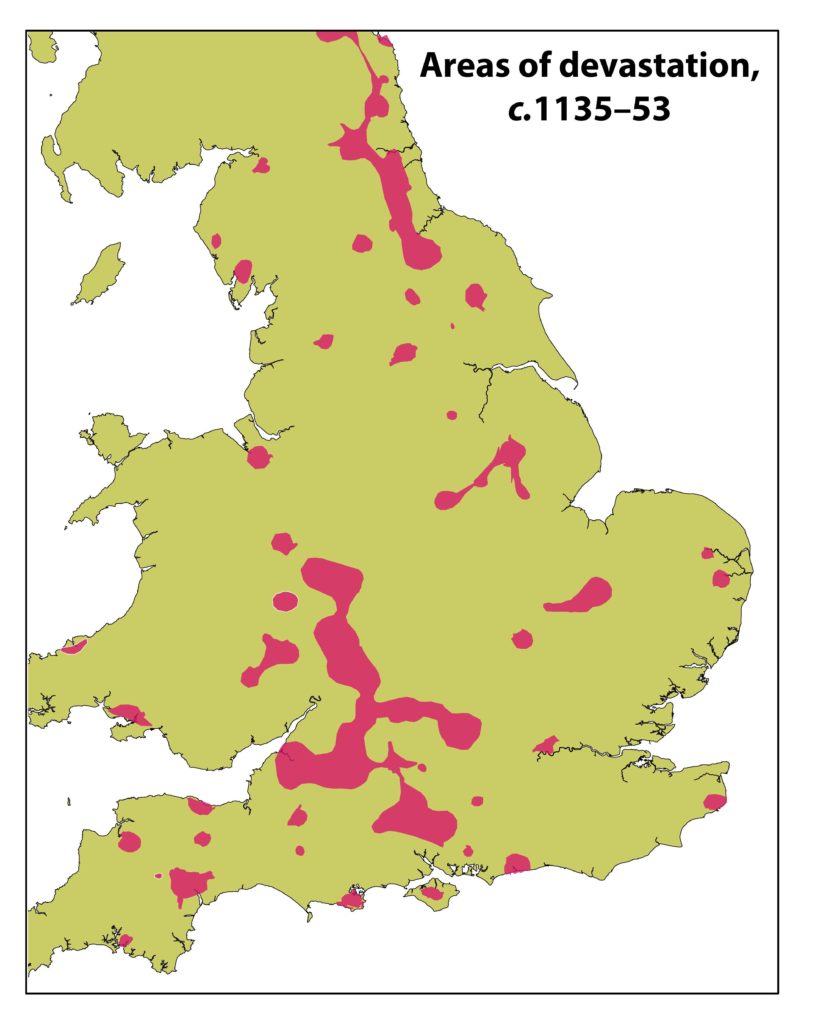

In terms of the big question for historians — whether we genuinely see ‘anarchy’ in mid-12th-century England, or whether revisionist views that downplay the levels of chaos and violence are vindicated — what did our work show? Anarchy in the UK or business as usual? Is it playing safe to say that the material evidence of archaeology shows a bit of both? On the one hand, everyday material culture, such as pottery for example, shows precious little evidence for any Anarchy-period ‘event horizon’ in the archaeological record, and there are signs that in certain spheres, such as sculpture for example, this was a period of experimentation and investment in the arts. On the other hand, our mapping of conflict events and, for example, coin hoards (which can be argued to provide an index of insecurity) show that in those areas of the country where it was focused, the conflict hit the landscape hard. The fortification of churches and even cathedrals (Hereford’s had catapults positioned on its tower!) was just one indication of how the rules of war were being stretched. The focus of conflict in the Thames Valley and Wessex also shows that this was not a struggle over peripheral or separatist regions, but for the very heartland of English kingship. But the area of life brought into the sharpest focus by the archaeology is the rise to prominence of local lords and of the seigneurial image —not just through castle-building, but through investment in sculpture within parish churches and through an unprecedented boom in monastic foundation, for example. As local lords made their mark on local landscapes, this was unmistakably a period of image-making as well as war-mongering.