Posted by Thomas Chadwick

4 October 2017Having finally submitted my thesis on Norman ethnic identity, I decided to celebrate by taking a holiday. And what better place for a young Norman historian to visit than Sicily?! It’s somewhere that combines exciting historical sites with the sun and warmth that seemed to bypass Devon this summer… Plus, as a newly-trained Norman expert, I was excited to follow in their footsteps and see some of the famous locations that I had read so much about. I confess that my itinerary (and thus this blog) was heavily biased towards Siculo-Norman history, though some of these sites may also whet the appetites of scholars interested in the Romans, Byzantines, Muslims and Swabians. In the interests of space, however, I will keep to what I consider the top four sites in Sicily for Norman historians and enthusiasts.

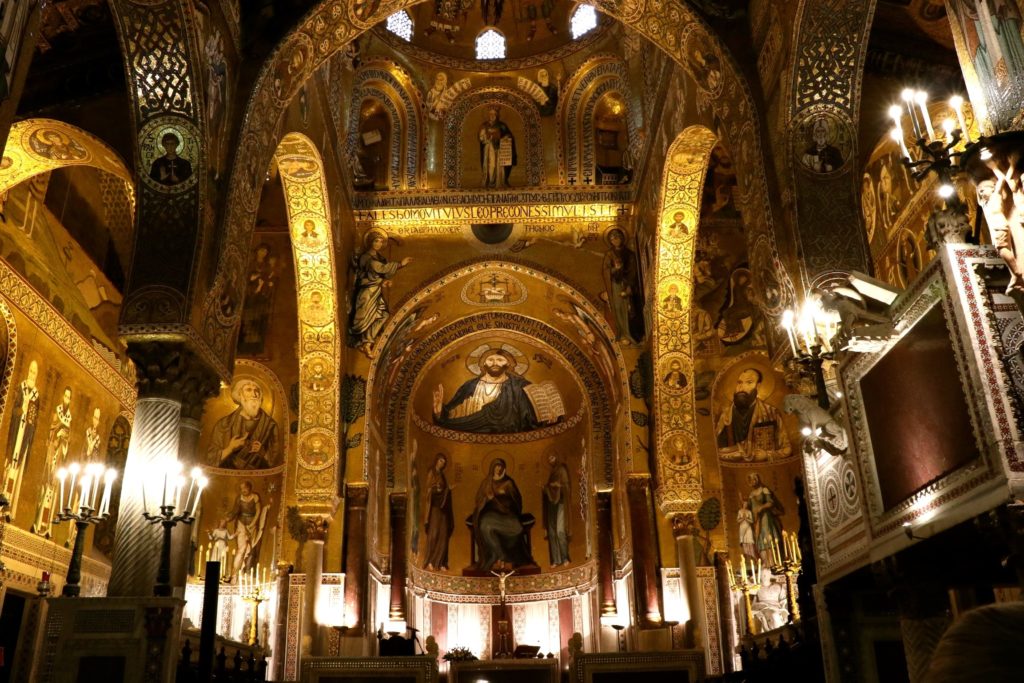

My first choice is the capital city Palermo, partly for its sites, but also for its archives. I spent a morning in the Biblioteca centrale della Regione siciliana looking at one of the few surviving manuscripts containing Geoffrey Malaterra’s history of the Normans. Admittedly, this qualified more as work than holiday – but it was too good a chance to miss. The fragmentary manuscript, containing only the first book of the text, is notably small, measuring approximately 7 inches tall and 5 inches across, and I was thankful to be lent a magnifying glass, an essential piece of kit I had foolishly forgotten. When the library closed at one o’clock, I was forced both to relinquish the manuscript and to see what else Palermo had to offer. One of the main sites is Palermo Cathedral, which houses the tombs of various kings and emperors, including the second Norman ruler, King Roger II. A short walk away one can find the Martorana, a co-cathedral dedicated to Saint Mary, founded and built by George of Antioch, who was an advisor to Roger II in the 1140s. The Martorana contains some of the most impressive Greek-style mosaics of the period, perhaps the most famous of which is a portrait of Roger II being crowned by Christ. However, these mosaics are rivalled by those in the Palazzo dei Normanni, the seat of power of the Norman kings and home of one of the oldest European parliaments. The Palatine Chapel and ‘Roger Hall’ of the palace boast mosaics from the 1130s, 1140s, and later, depicting biblical and secular hunting scenes, and are just as breathtaking. Both sites clearly reflect the multicultural society in Sicily during the years of Norman rule.

To the east of Palermo one can find the castle of Caccamo, a spectacular example of a Norman fortification, which was built by Matthew Bonnellus in the twelfth century. Although originally a Norman site, it has been extended over the centuries and I was particularly struck by some of its later early modern features, particularly a devious sixteenth-century addition to a private chapel. Unwanted guests praying in the chapel could fall victim to a secret trapdoor leading to a pit 35 metres deep. As if this were not enough, at the bottom upright swords were supposed to finish the victim off! This is something that might appeal to those family members or friends less enthralled by the Normans, especially those who enjoy the gory thrills of Game of Thrones.

The ancient city of Enna rises 931 metres above sea level. Known as Castrogiovanni during the medieval period, it was renamed around 1927 on the orders of Mussolini to reflect its ancient name. My main point of interest here was the Castello di Lombardia, a fortification situated at the east of the city. Once an important Byzantine stronghold, its foundations are the oldest elements of the castle, some of which were repurposed for the thirteenth-century walls constructed under the Holy Roman Emperor and king of Sicily, Frederick II. The fortification was no doubt daunting even in the Byzantine period and Muslim forces are believed to have resorted to crawling through the sewers to gain entry when they captured the castle in 859. Centuries later Enna played a decisive role in the Norman conquest of Sicily under Roger and Robert Hauteville. According to Geoffrey Malaterra the Normans defeated a vastly superior Muslim force on the banks of the river Dittaino in the summer of 1061, forcing them to retreat to Enna. It was, however, to take over twenty years, the building of another fortification nearby at Calascibetta, and a cunning ambush before Roger wrested Enna from Muslim control, a testament, no doubt, to the strength of the castle. Nevertheless, the Normans left their mark in the form of the keep, which still dominates the landscape today.

My final recommendation is the the town of Erice, which overlooks the city of Trapani at 750 metres above sea level. Here I made straight for the Castle of Venus, a Norman fortification built upon an ancient temple to a goddess of fertility, which was later appropriated for Venus by the Romans. The surviving ruins date back to the twelfth century but archaeological excavations in the 1930s discovered traces of the ancient building – legend even attributes the oldest section of the wall to the mythical Daedalus. Roger Hauteville is also credited with founding the nearby Chiesa di San Giuliano in 1076, one of the first churches built in Erice, though the surviving building dates from the seventeenth-century.

Sicily boasts a great wealth of incredible sites and monuments to history but during my visit I was struck by a notable disparity between certain sites. While the most popular destinations thrive on the tourism industry others are neglected, with crumbling walls and severely vandalised noticeboards pointing to a woeful lack of funds. Such issues have not gone unnoticed in Italy. Only this summer the Italian government announced their plans to give away over 100 historical sites, including medieval castles and monasteries, to those who could demonstrate a solid plan to renovate the properties into tourist hotspots. Unfortunately, none of these properties are located in Sicily. What may become of the less popular sites here is uncertain; while the cheap, or even free, admission to many of them is a welcome boon to financially concerned researchers and holidaymakers, it speaks volumes for their future. These fascinating sites are a testament to the remarkable impact of the Normans and other peoples on Sicilian history and culture – one can only hope that they will remain open (and intact) for a long time to come.