Posted by James Gordon Clark

8 December 2017‘We’ve found a body. We’d like you to help us with our enquiries’. An unnerving telephone message to pick up amid the usual end-of-term pressures, but as it turned out I was wanted only as a witness at a distance of some 550 years.

Canterbury Archaeological Trust have been leading an excavation at St Albans Cathedral as a prelude to the construction of a new welcome centre which is the centrepiece of their project, Alban, Britain’s First Saint, funded by the Heritage Lottery Fund.

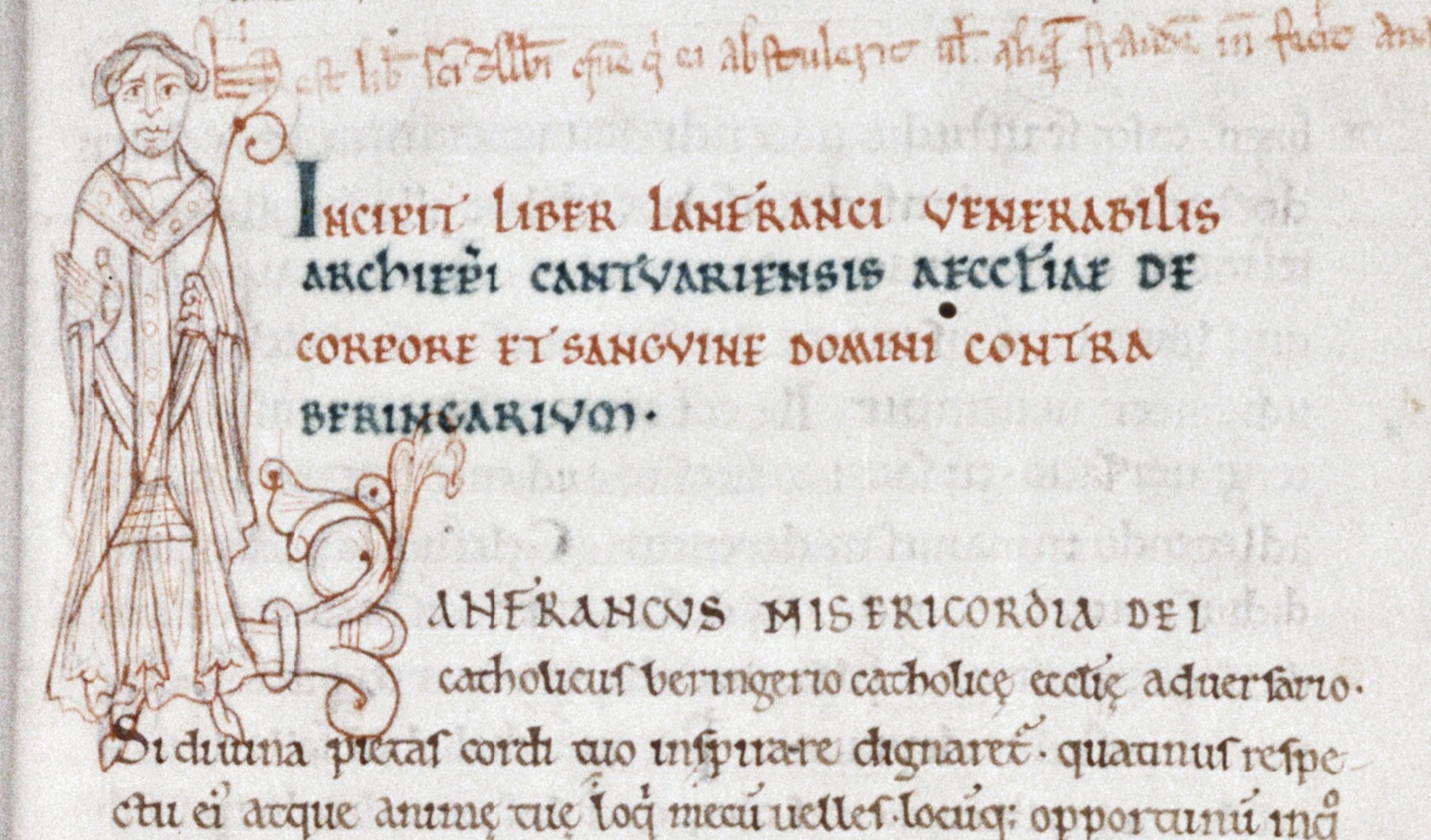

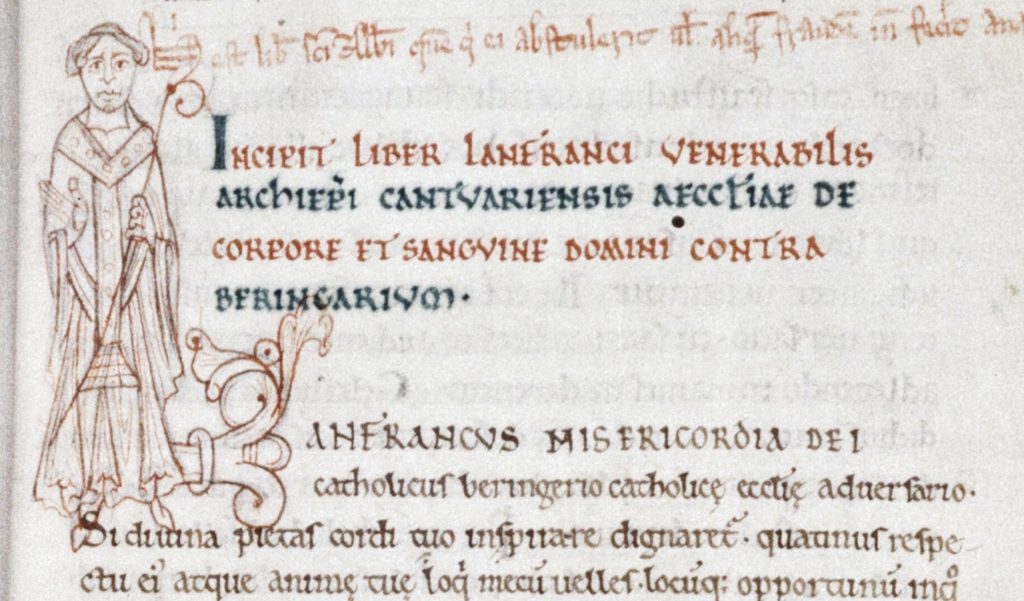

The dig has already offered up fresh insights into the early history of the Benedictine Abbey, uncovering the footings of the apse chapels that were a central feature of the devotional scheme of the Norman church built by Paul of Caen, the Norman monk entrusted with the revival of the old Saxon monastery by Archbishop Lanfranc of Bec. Paul’s abbey was quite different from the St Albans known from later medieval sources, not least in the attention given to saints’ cults other than the so-called protomartyr, Alban. The Norman church was made ready to receive altars and relics of the then more modish English saints, Cuthbert and Wulfstan.

The unidentified burial has been revealed after clearing a sequence of much later burials, of those citizens of St Albans who worshipped at the former abbey in the eighteenth century when it served as the town’s parish church. Beneath these remains the archaeologists have uncovered the traces of a substantial rectangular structure which would have projected southwards from the abbey’s presbytery. At its centre they have found a brick-lined tomb chamber still holding its original incumbent. The skeleton is of a male in advanced old age. To find a medieval burial intact was surprising in itself since earlier excavations have shown that the site has had a long history of the disturbance – and robbing out – of the higher status pre-Reformation graves. Even more unusual was the presence with the skeleton of three papal bullae.

Each one bears the inscription of Pope Martin V (1417-31), the pontiff whose election at the Council of Constance ended the Great Schism which had divided the Latin church at the height of the Hundred Years War.

While the presence of the bulls allowed the burial to be placed loosely on the abbey’s timeline, there was nothing more in the material evidence to suggest an identity.

So it was time to turn back to the texts. St Albans Abbey is well known to medievalists for its historical writing and a rich seam survives from the fifteenth century. For the period of Martin V’s pontificate in fact there are three substantial texts, an annal, a book of benefactors and a biography of an abbot. Each of these recount how Abbot John Whethamstede journeyed over the Alps in 1423 to attend the ecumenical council at Pavia.

While in Italy, he also made the journey to Roman Curia in the hope that he might secure an audience with the pope. On arrival he was struck down with a mortal illness and since plague was raging through the peninsula, causing the council delegates to swap Pavia for Siena, it was assumed that he would die. Pope Martin offered him the aid of his own physicians and when no cure could be worked, sent one of his officials to administer extreme unction. When all hope was lost, the abbot experienced a vision of St Bernard of Clairvaux, and on waking his recovery began.

When he was restored to full strength, he finally secured his hoped-for papal audience and, thankful for his survival, determined to do his best for is abbey by requesting three significant privileges from the pope. He was amply rewarded: Martin assented to his request and issued three bulls which the abbot hoped would distinguish St Albans from its Benedictine peers: to dispense the monks from the traditional abstention from meat during Lent; to permit the use of a portable altar at the monastery’s studium at Oxford and at their hostel in the city of London; to allow the abbot and convent to farm the income from the churches under their jurisdiction to laymen. Abbot Whethamstede gathered up his bulls and promptly returned home to St Albans.

Martin V’s bulls were an early success in a long career. Whethamstede held the abbacy twice, stepping out of office in 1441 when his health again failed but returning in 1452 and remaining then until his death in 1465, when he was probably at least 75 years old. He is remembered now for his achievements as a scholar and bibliophile, for his pioneering interest in Italian humanism and for his friendship with Humphrey, duke of Gloucester, younger brother of Henry V, and Protector during the minority of Henry VI. Yet his monks always remembered his audience with Pope Martin and in the biographical sketch they entered in their book of benefactors, they made much of his ‘three-fold’ character, surely a nod towards the bulls he had brought them all the way from Italy.

Certainly, the episode was well enough remembered for the abbot to be laid to rest with these trophies, and the biography tells us that the chapel Whethamstede built for himself was, yes, projecting southwards from the presbytery.

A fitting reburial is planned. And so, unexpectedly, it seems the first to be welcomed across the threshold of the abbey’s new welcome centre will be one of its own abbots.