Posted by James Gordon Clark

5 February 2018Eminent Churchillians have been all a-quiver. Darkest Hour has carried their subject far beyond his familiar home in the Culture pages of the serious newspapers to set him trending, everywhere. And the academic eminences have themselves been pulled into the spotlight, called on to share their expertise in every media forum, from the Today programme, to the Chris Evans’ Breakfast Show, just in case any of us had forgotten how Britain found itself in the spring of 1940.

But this flurry of attention has left them conflicted. They have been in awe at the spectacle of Neville Chamberlain’s gaunt, grey profile reanimated so perfectly that it might be an original newsreel, remastered in HD. But then they have been deeply troubled to see cabinet meetings convened in the War Rooms in May 1940 when everyone – of course, literally, everyone – knew they did not move there until September when the bombing started. And the spectacle of their Grand Old Man stepping on to the Tube to focus-group with the Great British Public has left them positively queasy.

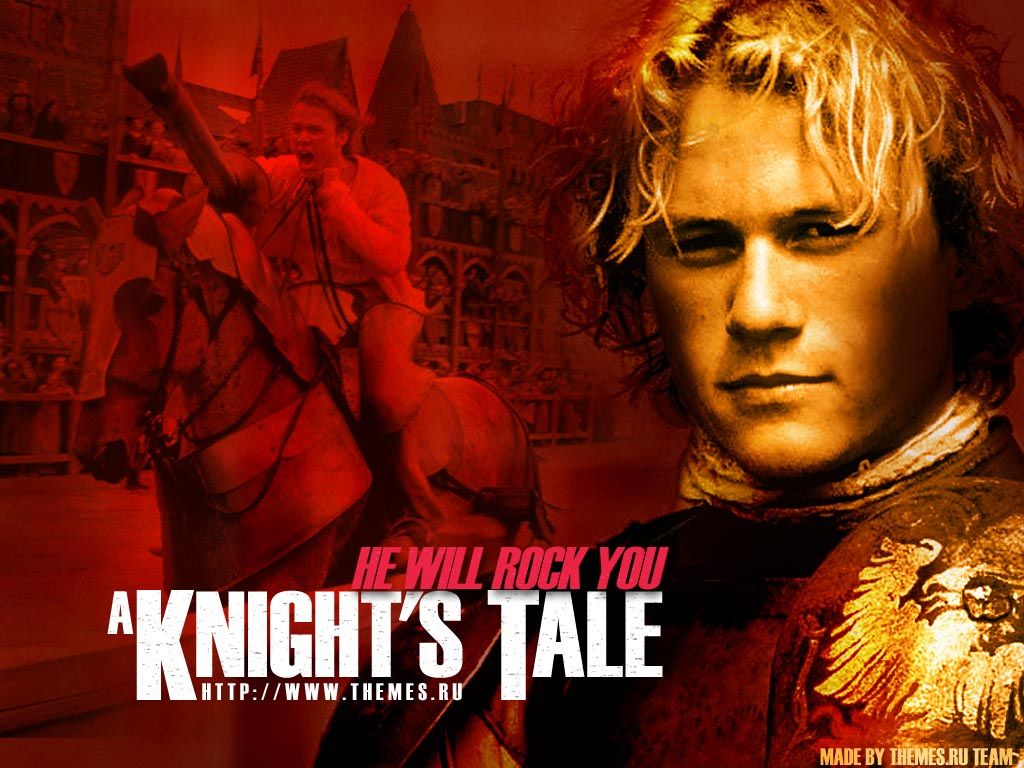

Watching their discomfort, the medievalist might be heard to mutter, ‘Welcome to our world!’. Conscious anachronism for dramatic effect – the PM reaching out to ordinary people in their time of peril his people in time – is often the least of our worries when our period makes it on to the screen. Apparently the Middle Ages are so remote from anything that the viewing public knows (or cares to know) that there is no question of trying to recreate it as it was. On the contrary, as a Lost World, there is a licence wholly to reinvent it. So the Benedictines of 13th-century Italy become Mafiosi in a mountainous redoubt – The Name of the Rose (1986) – the battling of Bruce, Balliol, Wallace and Edward I becomes a Six Nations match at Murrayfield – Braveheart (1993) – and the professional tournament circuit between Crecy and Poitiers is recast as something akin to a mad, muddy summer of festivals, from the Big Weekend, to V, via Glasto – A Knight’s Tale (2001).

And now, in the pursuit of Box Office (or Box-Set) success, it seems there is a determination to make the medieval truly out of this world. Judging from the messages in my inbox, it does seem that there are viewers of Game of Thrones who are quite satisfied that its medieval vision, more Middle Earth than Middle Ages, has more to offer than the other one, so tiresomely grounded in, erm, history.

So, it was with no small scepticism that I responded to an approach to act as historical consultant for the filming of a mini-series of Philippa Gregory’s The White Princess, her novelised account of the union of the houses of York and Tudor after 1485. The BBC TV series based on the prequel novel, The White Queen, had met sharp criticism for its sense of period which was flimsy even by the usual standards and was a poor reflection of Gregory’s own commitment to research.

Meeting the producers and directors, I was struck immediately by their up-front acknowledgement that the screen has generally got the Middle Ages wrong. I was also impressed by the research they had already done. The producers and I digressed very happily on Cardinal Morton and the pre-Reformation church. The director slated to supervise the Battle of Stoke (1487) displayed a disarmingly detailed knowledge of the formation of the battles, that is the deployments of force mobilised by Henry Tudor and the Yorkist rebels. She also knew a good deal about the German musketeers and their legendary leader, Martin Schwartz. I have to admit it was difficult not to be enticed by the prospect of bringing to an audience an historical moment in which we glimpse the coming Military Revolution, archers rendered obsolete by the handgun. Their grasp of the dynamics of the period was matched by an awareness of the landscape and environment in which it was played out. Before I became involved, buildings that were right for a fifteenth-century story had already been chosen as locations, Sudeley Castle, Gloucester and Wells cathedrals. I was especially pleased to find that the production team were well aware of the role of Gloucester in the short life of Henry Tudor’s eldest son, Prince Arthur, who for a time was entrusted to the tutelage of the abbot of the Benedictine monastery.

I agreed to take on the consultant role and soon found myself following the crew on their tour of these West-Country locations to give the nod – and certainly the occasional critique – to the scenes they were staging. Of course, White Princess is above all a portrait of a marriage and the bread-and-butter filming had no need of my watchful eye, as Lizzie (i.e. Elizabeth of York) and Henry Tudor played out their lively relationship framed only by flickering candlelight and the faint suggestion of linenfold panelling. But the story also tells how that relationship weathered the storms of a realm still profoundly unsettled after the Battle of Bosworth. The team were eager to show the armed rebellions that repeatedly cut through the connubial calm of Mr and Mrs Tudor. By far my longest day on location was spent at a picnic bench in Bradford-on-Avon taking the director through each turn and twist of the day’s fighting at Stoke. I also did my best to talk her out of representing Warbeck’s hastily abandoned stand-off at Taunton as a battle. Ever with an eye to diversity, she warmed to the reality of cosmopolitan armies. Now I was called on to check the accuracy of the non-English dialogue, and after verifying the insults with which Schwartz and his men showered their opponents, I was also given charge of the exchanges at the Burgundian and Spanish courts.

The team were excited by the prospect of staging battles but the other set-pieces that punctuate the drama, the ceremonial of coronation and marriage, made them strangely agitated and anxious. Above all, it was the fact that these were conspicuously sacred acts that seemed to unsettle them, that they would now be obliged to orchestrate priests and their liturgy. Of course, it was no problem to establish the rite used for the first Tudor coronation; Henry and Elizabeth’s marriage ceremony is also well-documented. The greater challenge was condensing it to a handful of scenes, significant in the context of the ceremony itself but suited also to the dramatic pitch the director had determined for this episode. Here too there was a problem of language, or at least for the actors. Of all the tasks I took on, the strangest was surely speaking the Latin into my phone’s voice recorder and emailing it across so that Kenneth Cranham – playing Cardinal Morton – could capture the fifteenth-century enunciation.

This at least was a little less out of my research comfort zone than my final task, poring over the fabrics in the costume department to pronounce on the colours and textures that were right for Lizzie and wrong for Lady Margaret Beaufort. In fact, the King’s Mother’s wardrobe is as well-documented as her personal piety. By the 1490s, it appears the only colours she could countenance wearing were ‘tawny’ and black. The costumiers took this message to heart, although their designs evoked somewhat less of a sense of late medieval contemptus mundi piety than they did of Maleficent.

There was also a moment’s tension over how to clothe a cardinal (Morton). They seemed to have bulk-bought purple chenille before I came on board so it was a battle to bring them to an acceptance that Morton’s generation was the first to be dressed in the classic red costume.

Of course, the predictable result was that many of the pains that I and others took over six months did not make the final cut. The ceremonial suffered especially, snipped and trimmed between close-ups with the liturgy consigned to a dimly audible backtrack. What aired, first in the US in April 2017, and in the UK in November, showed much more of the personal than the historical drama. But it did succeed in challenging at least some of my preconceptions. There was a genuine interest on our Middle Ages in the team – producers, directors, actors – that suggests that all is not yet lost to the likes of John Snow and Tyrion Lannister.