Posted by Catherine Rider

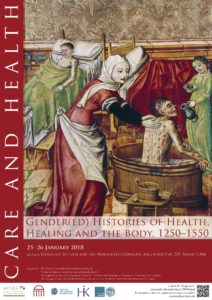

20 February 2018 At the end of January I went to a workshop at the University of Cologne, run by a.r.t.e.s. Graduate School for the Humanities and expertly organized by Eva-Maria Cersovsky and Ursula Giessmann. It focused on ‘Gender(ed) Histories of Health, Healing and the Body, 1250-1550’.

At the end of January I went to a workshop at the University of Cologne, run by a.r.t.e.s. Graduate School for the Humanities and expertly organized by Eva-Maria Cersovsky and Ursula Giessmann. It focused on ‘Gender(ed) Histories of Health, Healing and the Body, 1250-1550’.

I’ve long been interested in this area, which is important for my own research on medieval infertility, although thanks to other commitments in the last few years I am not as up to date on the scholarship as I would like to be. The workshop brought together a small group of scholars from the USA, Canada, the UK and Hungary as well as Germany, and it was good to hear about the work being done in these countries, as well as to gain feedback on some of my own work in progress on infertility, gender and old age in the Middle Ages.

The papers covered such diverse topics as hospitals, royal and aristocratic courts, saints’ cults, contraception, medicine, and pharmacology. One particular strand of discussion running through a number of the papers, which perhaps takes its cue from similar work on the early modern period, focused on how scholars can get at medieval women’s medical knowledge and the ways in which they provided healthcare. As the American historian Monica Green showed back in the 1980s, very few medieval women are formally designated as medical practitioners in our sources, using terms such as ‘medica’, surgeon, or even midwife. However, the majority of medieval healthcare happened in the home, and it seems likely that much of this work was done by women. By the end of the period we can see elite women who clearly had some expertise in medicine. Thus the keynote lecture, by Sharon Strocchia, described the medical knowledge of women at the sixteenth-century Medici court, and showed that these elite women were concerned with a variety of medical issues in their households and were clearly well informed in their dealings with court physicians. This kind of information is harder to come by for earlier centuries but papers on a range of source materials including miracle narratives, medical recipes, images of miraculous healings and hospital records suggested some possibilities.

I still need to think about how to work all of this into my own research but the conference got me thinking much harder about the role of gender in my sources: in particular, who knew what about reproductive disorders in the Middle Ages, and who offered what kinds of medical and healthcare advice relating to fertility?

Catherine Rider, Senior Lecturer in History