Posted by Edward Mills

5 October 2018It’s not all that often that some news genuinely makes you jump out of your seat in excitement. One such occasion came for me a couple of months ago, when my email inbox, usually reserved for reminders about overdue library books, served up a cracker: namely, that a storyteller, Rachel Rose Reid, was working on a retelling of the thirteenth-century French text, Le Roman de Silence, and was looking to connect with academics who could inform her work. For someone like me, who works with medieval French texts as part of his PhD, this opportunity was just too good to pass up.

Funnily enough, though, the wave of excitement that the email inspired — and that saw quite possibly the fastest email reply I’ve ever written — was probably not too dissimilar to the eagerness felt at the moment when Rachel’s source text was first uncovered. The story of behind the Roman de Silence is almost as famous as the Roman itself: it survives in just one manuscript, currently in the care of the University of Nottingham’s Special Collections, which was discovered as late as 1911 in a box marked ‘old papers — no value’.

It’s with the narrative of the Roman de Silence, however, that Rachel really works her magic. After King Evan of England declares that no woman shall ever inherit in his kingdom, one of his vassals, Cador, agrees with his wife Eufemie that their newborn daughter, Silence, should be raised as a boy. There follows a debate between the allegorical figures of ‘Nature’, who unsuccessfully attempts to persuade Silence of the folly of their ways, and ‘Nurture’, whose intervention leads to Silence undertaking a range of traditionally masculine pursuits. These questions of gender and upbringing form some of the key themes of this 6,000-line piece, which Rachel has separated into a trilogy. With all this in mind, I jumped at the chance to find out more; still buzzing from the free press ticket to a performance the night before, I sat down to talk to Rachel about how she went about adapting Silence, as well as her own experience with the work.

So first things first … you’re known as a ‘storyteller’, and work with both children and adults. Many of the people reading this blog might not be all that familiar with what exactly it is that a modern-day ‘storyteller’ does; could you give us a brief introduction of what you try to achieve when you work with stories like Silence?

The first thing to consider when talking about ‘storytelling’ as a vocation is really just how many ideas it encompasses. There are many different storytelling traditions around the world, and these all adhere to their source material to different degrees; I suppose that a Shakespeare performance would be at one end of this spectrum, where going to see (say) Hamlet several times, you’d expect to see a very similar performance on each occasion. In that case, then, there’s got to be something in the performers’ interpretation of the text that would bring it alive for you. At the other end of the scale, we have the folk traditions that are still alive in Ireland and Scotland, where the storyteller will know the ‘marks’ that they have to hit, but won’t be too concerned about sticking rigidly to a certain pace as they move through them. I work with both forms: in performance poetry, my words are the same every time, whereas in shorter storytelling – up to about 20 minutes – I have ‘markers’ and improvise between them. Silence, though, is an epic endeavour, and requires some combination of the two. I’m more certain of what I will be saying and doing, so that I can take the audience on a complex narrative and emotional journey, but my relationship with the audience in my performances is far more porous than you might otherwise expect from the image conjured up by the word ‘performer’. In a way, my work is a combination of the skills of stand-up comedy and guiding group meditative visualisation: even if Silence contains many of the same elements from night to night, every show is made different by the different audiences. I try to create a synergistic relationship between myself as the storyteller and the audience, where can I respond to things that we experience in the room while still remaining inside the ‘landscape’ of the story.

There was one wonderful point in the performance when you actually asked the audience to contribute — you asked us what words we would use to describe a forest scene …

That’s one obvious example, but in storytelling, ‘involving the audience’ is something that also happens even when the audience aren’t speaking! This question of audience participation is actually really intriguing for me in the specific context of how Heldris de Cornuaille, the author named in this text, would have worked: there’s a moment later in the story when the counts of France are debating how their King should react to receiving a letter, and whenever I think of this particular episode, I’m reminded of Grace Hallworth, a storyteller originally from Trinidad, who will always invite her audience to ‘chip in’ with their thoughts at any ‘decision point’ in a story. I’ve always wondered whether this sort of audience interaction would have happened during medieval storytelling: would the performers of texts like these have elicited debate from their audiences? One element in my version of Silence was only added a couple of days ago, and it was done in response to audience engagement: whenever I used to quote Heldris’ line that ‘some people swore in sorrow’ (when asked to swear loyalty to the law that women will be barred from inheritance), audience members used to call out — totally unprompted — that it was the women who were doing it, so I started asking my audiences who they thought it was. We often assume that that questions like these are rhetorical, but I’m not so sure …

I was very struck by one of the modifications that you made to the text: that of the wedding. In Heldris’ text, the wedding (between Cador and Eufemie) finishes before the counts’ feud that leads to women being barred from inheritance, and you weave a wonderful scene with minstrels from different countries telling increasingly elaborate stories …

Medievalists will know that the chivalric interactions between Cador and Eufemie in Silence are essentially a giant send-up of the Tristan and Isolde legend, but my audience — many of whom of course aren’t medievalists — won’t. That’s why I elaborate the minstrel scene when I tell Silence: so I can set up a repeated idea of what a ‘romantic story’ is, before the audience get to see me taking the mickey out of it! What’s more, these stories are the kind of ‘romantic story’ that we’re flooded with in popular culture today — what about rom-coms, where we essentially repeat the same narrative over and over again?

There’s often a contradiction in how people see the medieval period: somehow, popular culture imagines it both as a ‘purer time’ characterised by chivalry and knights in shining armour, and yet also as an epoch of abject misery and filth. What were your experiences of working with this particular period of history?

What is key to me, in bringing this story alive, is for my 21st-century audience to find the many connections that exist between our own experiences, those of Heldris, and those of the characters. We’re not doing faux medieval re-enactment here: I don’t want the audience to be scratching their heads over obscure terminology, or despairing over sections that seem over-egged to the modern ear. However, I’ve found that the plot points at the heart of Silence only need minor alterations for them to be understood today. Heldris has so much to say about topics that are both thrilling and troublingly familiar for us to hear today: equality, identity, religious dogma, sexual abuse, the damage done by an overbearing patriarchal structure … The legal matter of land and title is still going strong, too, both in our unspoken social norms and in the aristocratic echelons around which Heldris centres the story. Sometimes I think that the reason the text went missing for a few hundred years was simply that it was exhausted … In this text, I’ve been delighted to discover that this medieval writer-storyteller uses so many of the techniques that my peers and I use: satire, flippancy, sarcasm, self-deprecation, timing, and alternating between colloquial chat and grand dramatic imagery. I’m not planning to perform in rhyming couplets, but in working on this project, I have found great joy in discovering the world of medievalists, too. I’m looking forward to sharing this adventure with more medievalists, and I hope that by 2019 we will have several places where the entire story can be told.

As you can tell, Rachel and I certainly had a lot to talk about — so much, in fact, that we’ve decided to split this interview over two blog posts! In the second part of our interview, we’ll be talking a little more about some of the more specific challenges posed by retelling Silence, specifically how Rachel responds to the challenging topics addressed by the text.

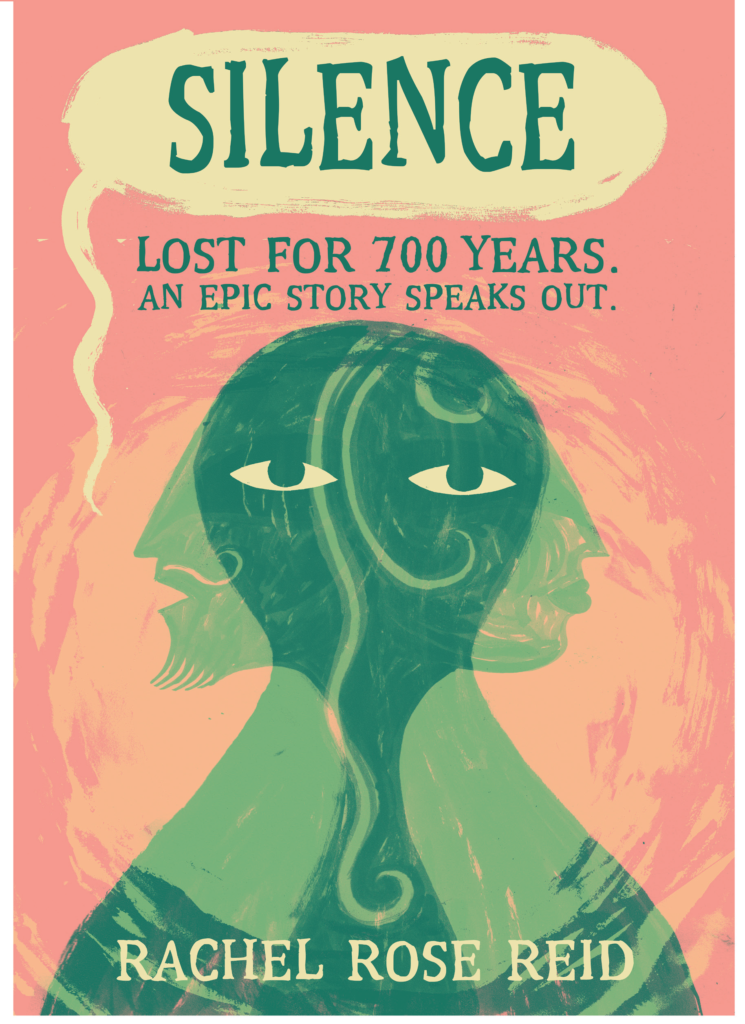

Rachel Rose Reid has toured Parts 1 and 2 of Silence during 2018, supported by Arts Council England, and is currently writing the final section. She is seeking partners, hosts, and grants to make it possible for her to perform the whole of her adaptation (possibly two sets of two-hour performances, so may require an overnight experience) at various locations during 2019. Please send ideas, suggestions and offers to mail@rachelrosereid.com; for more information, see silencespeaks.strikingly.com and rachelrosereid.com.