Posted by James Gordon Clark

5 January 2020Five hundred years ago, Henry Courtenay, earl of Devon (d. 1539), marked the coming of the New Year with a rare and costly gift for his king, Henry VIII: oranges (Earl Henry’s accounts do not record how many). Oranges were not unknown at the royal table – indeed Henry is known for his fondness for marmalade, then a rare Portguese treat which the king secured from an importer in Exeter – but they were an undoubted luxury, shipped from Iberia.

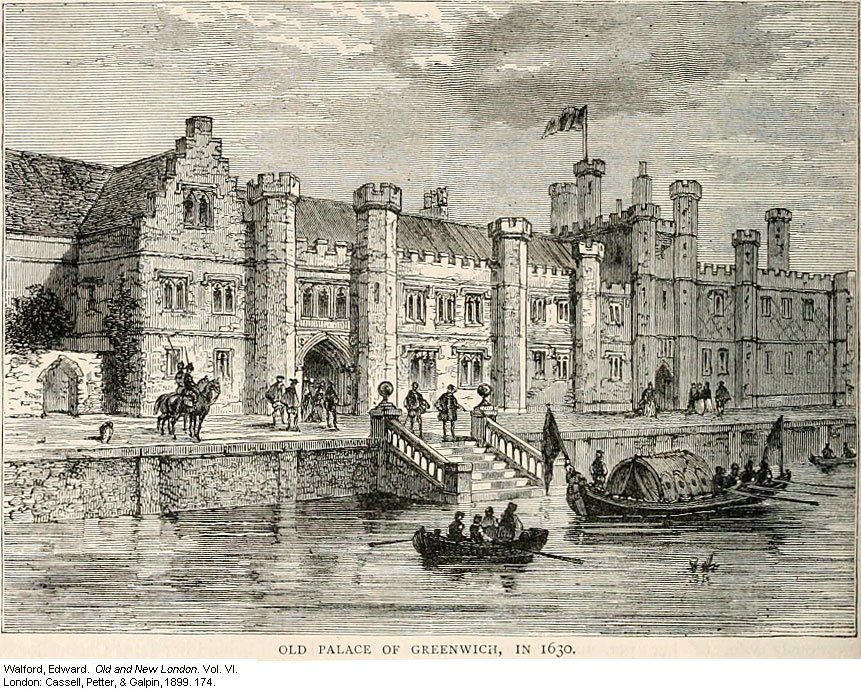

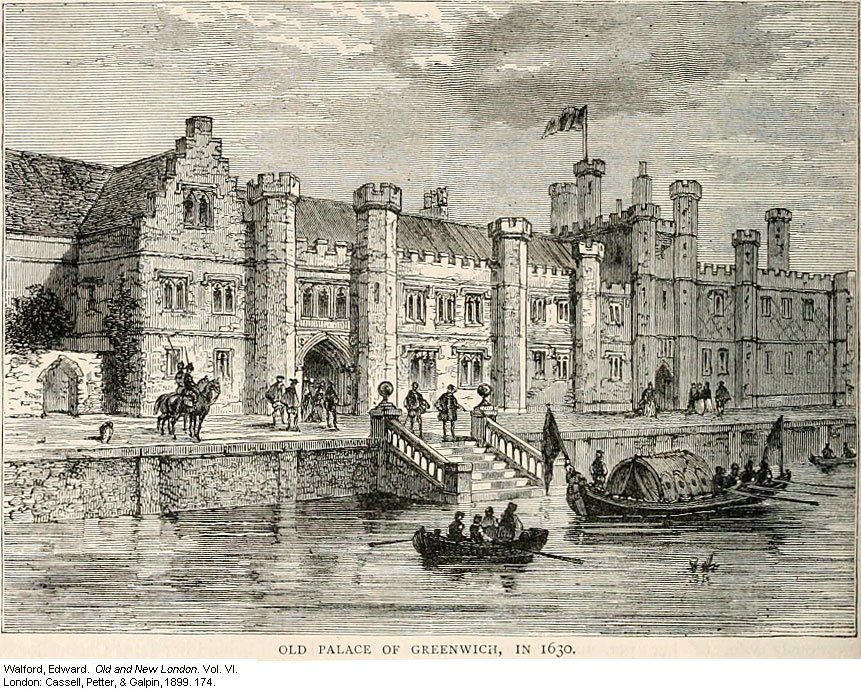

The Courtenay accounts do not tell how much the earl paid for them but he was clearly anxious over his investment as they do show the chain of paid assistants who saw to it that the precious cargo was carried down river to Greenwich Palace without mishap. Earl Henry, who was in the early stages of his rise to the status of royal favourite (which would culminate in his creation as Marquess of Exeter in 1525) was evidently determined to make this the most memorable of New Years. So solicitous was he of the twenty nine year old Henry’s enjoyment, he even paid a passerby to give up his cap, so that the royal head might be spared during a bout of snow-balling.

The giving of gifts at the new year was a well-established custom among the social elite in England long before the coming of the Tudors. Jocelin of Brakelond, monk of Bury St Edmunds, recalled at the turn of the thirteenth century that gift-giving at the Feast of the Circumcision (calculated in the Julian calendar as 1 January) was a ‘custom among the English’. In an account which to modern readers might carry a much later seasonal echo, Jocelin thought of his own abbot, Samson of Tottington (1180-1212), and asked himself ‘What can I give him?’. His choice was characteristic of a medieval Benedictine: he compiled an inventory of the churches held by the abbey showing their rentable value. Samson, Jocelin reported, was ‘very gratified’.

By the mid-thirteenth century the presentation of New Year’s gifts was conspicuous in royal circles. On one occasion, Henry III purchased 307 rings for distribution on 1 January. In 1242 he presented Beatrice of Savoy (c.1198-c.1267) with the figure of an eagle set with precious stones at a cost of £100, perhaps the equivalent of upwards of £70000 by today’s values. Although by no means routinely recorded, magnates and prelates in pursuit of royal favour adopted the custom, conscious of its currency. In mainland European courts it had become an established part not only of ceremonial practice but also of its political power-play. In the French court of the Valois monarchs the custom was refined as the étrennes, the giving of gifts to start the year with an element of surprise. This seems to have passed into the English royal court with the coming of the Tudors, perhaps another of the French and Burgundian tools of royal authority absorbed during his exile by the first Henry Tudor.

In the reign of his son, Henry VIII, the politics of New Year’s gifts reached a new intensity. The king’s accounts of his purchases and presentations are a precise index of who was present in – and conspicuously absent from – his favour. In their turn, those courtiers, magnates and churchmen aiming to turn the increasingly factional climate to their advantage gave New Year’s gifts a permanent place in their armoury. Never more so than after 1534, in the struggles to profit, and not to lose, from the King’s Reformation. At the decade’s end, after the deaths of two queens, the dissolution of most monasteries, and popular rebellion, the anxieties at the turn of the year were feverish. Henry Courtenay himself fell foul of the court politics at the year’s end in 1538 and was executed in the first week of January 1539. As it happened, Bishop John Vesey (1519-54) had been among the king’s company during that New Year and royal largesse extended to the bishop’s cohort of servants. One of the last monastic superiors still standing at this time, Thomas Goldwell, prior of Christ Church, Canterbury, sent £20 of gold as his New Year’s gift to the king on 15 January 1540 just eight weeks before he was compelled to surrender his ancient monastery into the king’s hands. Thomas Cromwell’s final and most fateful gift to his king on what turned out to be the last New Year’s Day he would see was his first meeting with Anne of Cleves (c.1515-57). Sadly for Cromwell, the king found he ‘liked her nothing so well as she was spoken of’. On 30 June 1540, writing from the Tower of London as the king’s ‘most miserable prisoner and poor slave’, he tried to persuade his master to remember the encounter differently. To no avail. Cromwell was executed at Tower Hill days later.