Posted by Edward Mills

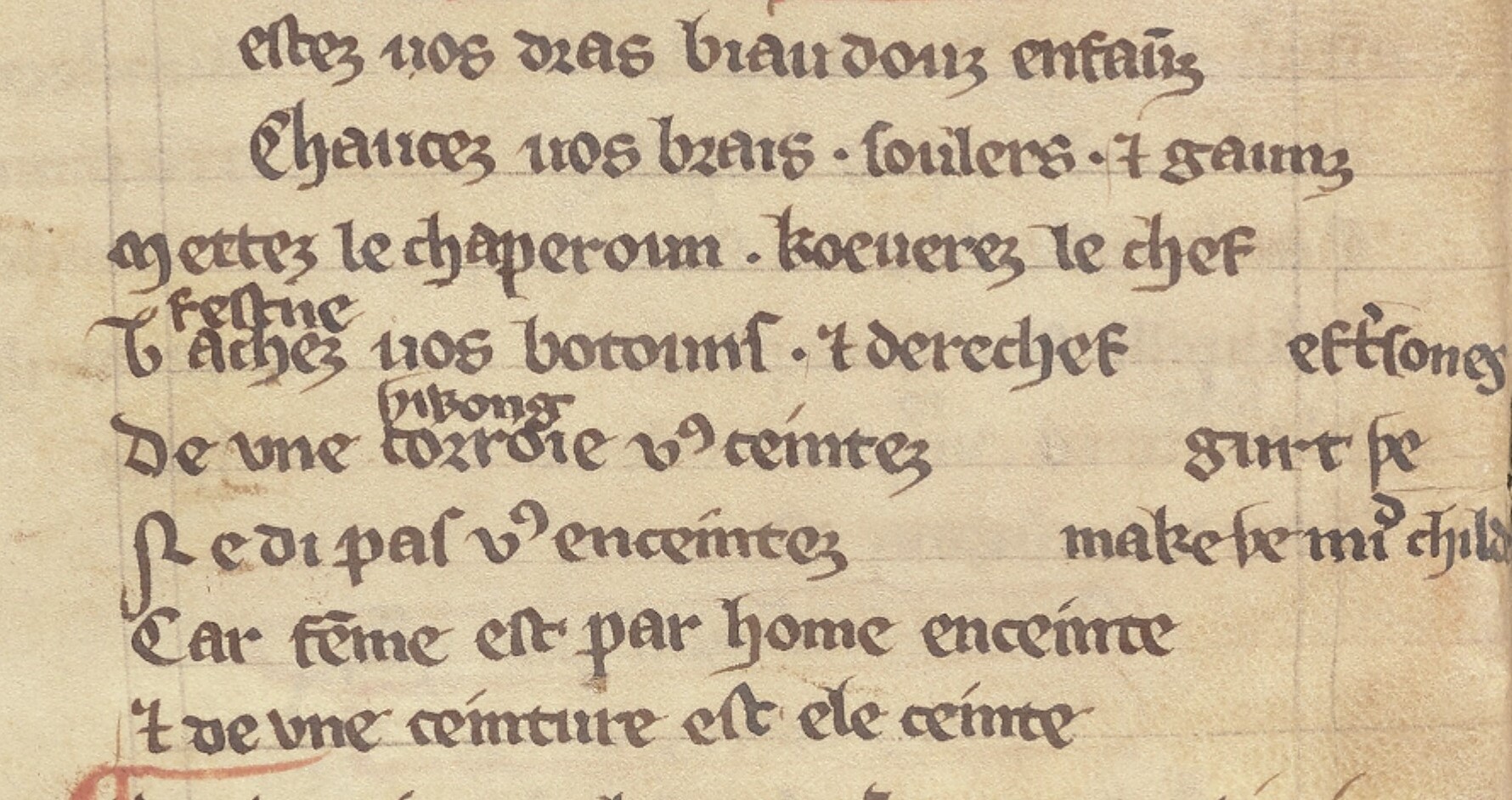

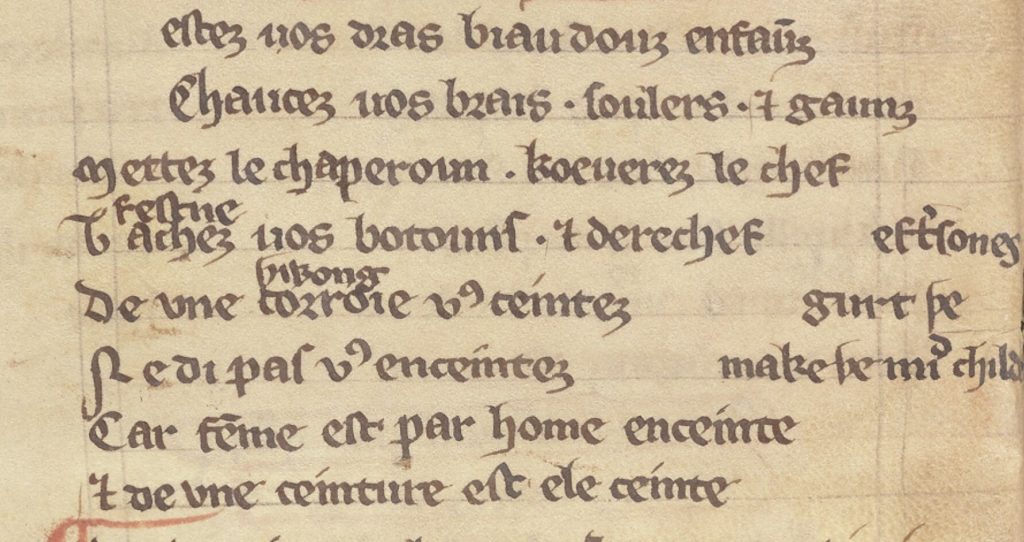

14 February 2020Vestez vos dras, biau douz enfaunz,

Chaucez vos brais, soulers, et gaunz. […]

De une corroie vous ceintez —

Ne di pas ‘vous enceintez’,

Car femme est par home enceinte

Et de une ceinture est ele ceinte.

Put on your clothes, my sweet child: don your breeches, shoes, and gloves. Lock up your belt-buckle — but do not say ‘knock up’, for a woman is knocked up by a man, but is locked up within a belt.

This somewhat risqué passage of French verse, written by Walter de Bibbesworth in mid-thirteenth-century England, would no doubt have provoked a few giggles among its audience. Its humour is difficult to capture in translation, but is clear even to those of us whose French is more than a little rusty: punning on the near-homophonic Middle French verbs ceinter (‘to do up a belt’) and enceinter (‘to impregnate’), the author offers a cautionary tale in how even the smallest of phonetic alterations can have a major (and often-unintended) impact on the meaning of a phrase.

The passage in question is from the longest of three medieval French texts attributed to Bibbesworth: the Tretiz. The Tretiz is an unusual text in many ways, presenting itself as a rhyming vocabulary that offers one-stop-shop for all your advanced French vocabulary needs, from brewing beer to describing one’s own body. Walter de Bibbesworth promises at the outset that he will not teach ‘le fraunczois qe cheascun siet dire’ (‘the French that everyone knows’), but instead claims that his text was written ‘pur gentyls home ou pur fyz de gentyls home enfourmer de langgage’ (‘to teach nobles or their sons language’). Despite this rather unexciting opening statement it soon becomes clear — partly through Bibbesworth’s aforementioned obsession with homophones and wordplay — that the Tretiz is no ordinary phrasebook or dictionary. Instead, the reader is treated to a 1,000-line rambling tour of all manner of scenarios, ranging from a detailed list of the noises made by assorted wild animals to an odd little anecdote about a dwarf whose attempts to fish in the river Seine are constantly frustrated by inclement weather.

Despite these strange digressions — or, perhaps, because of them — the Tretiz has become something of a touchstone for scholars working on language use in medieval Britain. Over the years, it (along with its remarkably varied tradition of Middle English glosses) has been referenced in research on subjects as varied as lexicography, social history, and language change, often with respect to both English and French. Much of this valuable work has, however, been limited by an incomplete editorial tradition: the latest critical edition of the Tretiz, produced by William Rothwell in 2009, offers a superb insight into the text’s glosses but is limited in scope to two of the text’s 17 witnesses. With previously-unknown manuscripts of the Tretiz emerging as recently as 2011, it has become clear that, as Rothwell himself noted as early as 1990, ‘The whole corpus of Bibbesworth manuscripts needs to be made available eventually in a full critical edition for use in lexicographical work on the development of both English and French.’

It is therefore very exciting to announce that, over the next 15 months, the work of producing the first complete edition of the Tretiz will be carried out in the Centre for Medieval Studies here at Exeter! Dr. Thomas Hinton (Senior Lecturer in French) has received funding from the UK’s Arts and Humanities Research Council Leadership Fellows scheme to develop a digital critical edition of all 17 known manuscripts of this challenging and fascinating text. I’m writing this blog post as the second member of the project team: for the next 15 months, I’ll be working alongside Dr. Hinton as the project’s Postdoctoral Research Associate. Dr. Hinton and I will be collaborating with the University’s own Digital Humanitiesteam to ensure that our edition becomes a vital resource for researchers from various disciplines, as well as one that makes full use of the flexibility and connectivity offered by the standards of the Text Encoding Initiative.

However, our project also has a broader aim: to raise awareness of the importance, both historically and in the present day, of multilingualism and language-learning. While much of our research as medievalists is built on the ability to read more than one language, there is a growing concern that language uptake in UK secondary schools is in decline, with students increasingly denied the opportunities to explore other languages and cultures. A medieval rhymed vocabulary might seem an unlikely solution to this very modern problem, but we’re keen to stress that, as the Tretiz itself shows, Britain has never been monolingual, and that understanding the complex connections between languages can only make our work — and, indeed, our lives — better.

We’re looking forward to providing several updates on this blog over the coming months as our work on the Tretiz starts to take shape. In the meantime, we warmly invite anyone with an interest in the project to follow us on Twitter, where we’ll be sharing shorter snippets from our investigations — and, once a week, some very special #TretizTuesday excitement!