Posted by Gregory Lippiatt

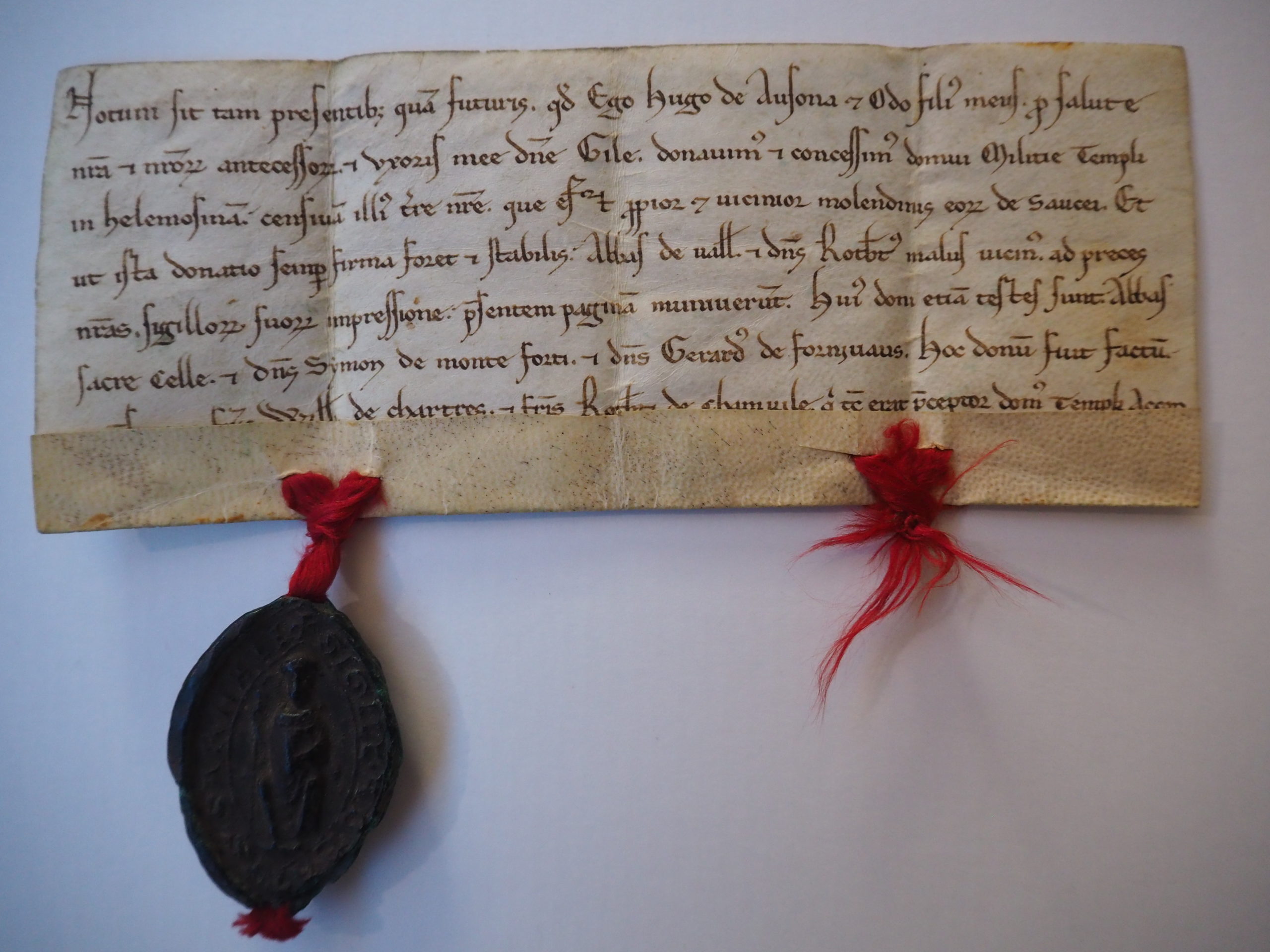

23 April 2020Almost ten years ago, during my doctoral research, I was rifling through boxes at the Archives nationales in Paris for the first time. Guided by preliminary references I had found in notes kindly provided by Prof. Nicholas Vincent, I was mining a very rich seam through the Ordre de Malte section of the S series. It was there that I stumbled across an undated and unpublished charter that seemed to have inspired no comment in any of my secondary reading (pictured above). Its anonymity may seem natural enough: it records a donation to the Knights Templar made by a father and son—Hugh and Odo of Essonne, otherwise unknown—of the census from some vague ‘land of ours closest and nearest to [the order’s] mills’ on the island of Saussay (between modern Itteville and Ballancourt, Essonne).

The rather flashy red silk cords and surviving green wax seal caught my eye, however, and I froze upon reading the witness list. As a first-year doctoral student, the novelty of handling medieval parchment was still quite fresh, and that electric feeling of connexion with the past found in archives has never left me. But this scrap of skin and ink promised to be particularly special. In addition to Simon of Montfort, the subject of my doctoral thesis, those present at the grant included the Cistercian abbots of Vaux-de-Cernay and Cercanceaux, Robert Mauvoisin, Gerard of Fournival, and the Templars William of Chartres and Robert of Chamville. The abbots had not only been among those white monks deputed to recruit and accompany the Fourth Crusade (1198-1204), but, along with Simon of Montfort and Robert Mauvoisin, opposed the crusade’s diversion to attack Christian cities such as Zara on the Dalmatian coast, finally leaving together for Syria in 1203 while most of the army sailed to its infamous destiny at Constantinople. Gerard of Fournival had no connexion with this group, but was a Third Crusade veteran and Plantagenet courtier who made an independent second voyage to Outremer in 1204. William of Chartres would become master of the Temple in 1210, while Robert of Chamville is noted in the charter as ‘commander of the Temple of Acre’, a position he held until sometime before 1207.

Here was, then, an original charter that had almost certainly been drafted in the Holy Land during the Fourth Crusade, between mid-1204 (the arrival of Gerard of Fournival) and autumn 1205 (the latest possible departure of Simon of Montfort). Subsequent searching on my part yielded only four other such surviving charters. This fifth example was brought to the commandery of Chalou-la-Reine (modern Chalou-Moulineaux, Essonne), either by the donors or by Templars returning to France from business or service in Acre. After the suppression of the order in 1312, the Knights Hospitaller took over the commandery, and the charter was eventually deposited in the archives of the commandery of Le Saussay itself, erected in 1356. It would remain there until the suppression of all religious orders during the French Revolution and the national confiscation of their possessions, at which point the document was introduced to its present home in the Archives nationales.

In addition to its rarity, this charter also reveals a good deal about diplomatic practices among the Templars in Acre at the turn of the thirteenth century, as well as the history of the dissenters from the Fourth Crusade. Among the first things to note are the physical elements of the charter that first arrested my attention: the red cords and green wax.

Seals were ordinarily attached with simple parchment or leather queues and cast in uncoloured brown wax. Cords made of dyed fibres such as those attached to the Essonne charter (left) or to a contemporary confirmation by papal legates of a dying crusader’s grant to the Templars (right) demonstrate status, while green wax emphasises the importance and perpetual significance of the document it seals.

These materials, likely along with the professional scribe who so neatly composed the charter, were almost certainly provided to Hugh and Odo by the Templars in Acre, suggesting a ‘luxury service’ for those crusaders who wished to extend the benefits of their experience in Outremer by endowing the order with property in the West. That the Templars in Acre were willing to lay out the red carpet even for donations as modest as that of the Essonnes is indicative not only of the Knights’ wealth, but also of an indiscriminate approach to property acquisition.

Closer inspection of the text, particularly of the witness list, yields a number of other conclusions. A distinction made between the witnesses—the abbot of Cercanceaux, Simon of Montfort, and Gerard of Fournival—and the Templars ‘in [whose] presence’ the grant was made sheds light on the purpose of such observers. While the witnesses are described as such in the present tense (testes sunt), the attendance of William of Chartres and Robert of Chamville is in the perfect (fuit factum); Robert’s office as commander is furthermore given an imperfect qualifier (tunc erat). A nearly identical diplomatic formula in a Champenois charter of 1201 (surviving in a vidimus, below) attests the presence of Templars at a grant made in Acre but only recorded once the crusader donor returned home.

Here, however, a distinction is made between the witnesses of the ‘fact’ or ‘matter’ (res) of the donation, and the ‘gift’ (donum) itself. By contrast, both the witnesses of the Essonne charter and the Templars are associated with the actual donum of the grant. But while both the crusaders and the Templars attended the Essonne grant, they did not all serve as witnesses. Quite apart from the fact that, as beneficiaries, William and Robert were interested parties, the substance of the gift—the census on the Essonnes’ land—was in France, and neither Templar could be relied upon to return from his active service in Outremer. The true witnesses, however, all expected to make the voyage home, where they could vouch for the authenticity of the Essonnes’ act. The Templars in both Syria and France therefore distinguished between the persistent identity of the witnesses and the temporally limited role of the representatives of the order, who were too distant to be consulted or easily verified.

More indirectly, the conjunction of the abbots of Vaux-de-Cernay and Cercanceaux, Robert Mauvoisin, and Simon of Montfort testifies to the continued cohesion of the group that abandoned the main crusade army over a point of principle in 1203. The continued affinity between Simon, Guy of Vaux-de-Cernay (who had long been a friend of the Montforts), and Robert Mauvoisin through the Albigensian Crusade (1208-1218, Simon’s death) has been much discussed elsewhere; the inclusion of Hugh of Cercanceaux, who, unlike the others, had no connections with the forest of Yveline (south-west of Paris), shows that this association was not derived solely from regional identity. Indeed, the presence of an outsider such as Gerard of Fournival among the witnesses may confirm the importance of shared ideals. Before sailing east, Gerard petitioned for a royal licence to move a weekly market in his Norman lands from Sunday to Thursday, in line with the reforms preached by the Parisian schoolmen linked to Guy of Vaux-de-Cernay and enacted in 1212 by Simon of Montfort in the Statutes of Pamiers, a constitution for his conquests in the Albigensian Crusade. In contrast with the recriminations of Fourth Crusade apologist Geoffrey of Villehardouin, who accused them of wishing ‘to disperse the host’ at their departure from Zara, Simon, Guy, and their companions remained physically and morally united throughout their expedition to the Holy Land.

A decade ago when I discovered this charter, I was principally interested in this last dimension: its value as an independent documentary testimony to Simon of Montfort’s pilgrimage to Outremer. I have, however, continued to come back to this remarkable, if brief, bit of parchment over the years and tried to tease out some of the light it can shed through its peculiarities. I hope these musings have demonstrated its importance, not only as an uncommon survival but also as a window into medieval approaches to documents, particularly in the context of crusading, at the turn of the thirteenth century.

Featured image: Paris, Archives nationales, S 5150A, no 16