Posted by James Gordon Clark

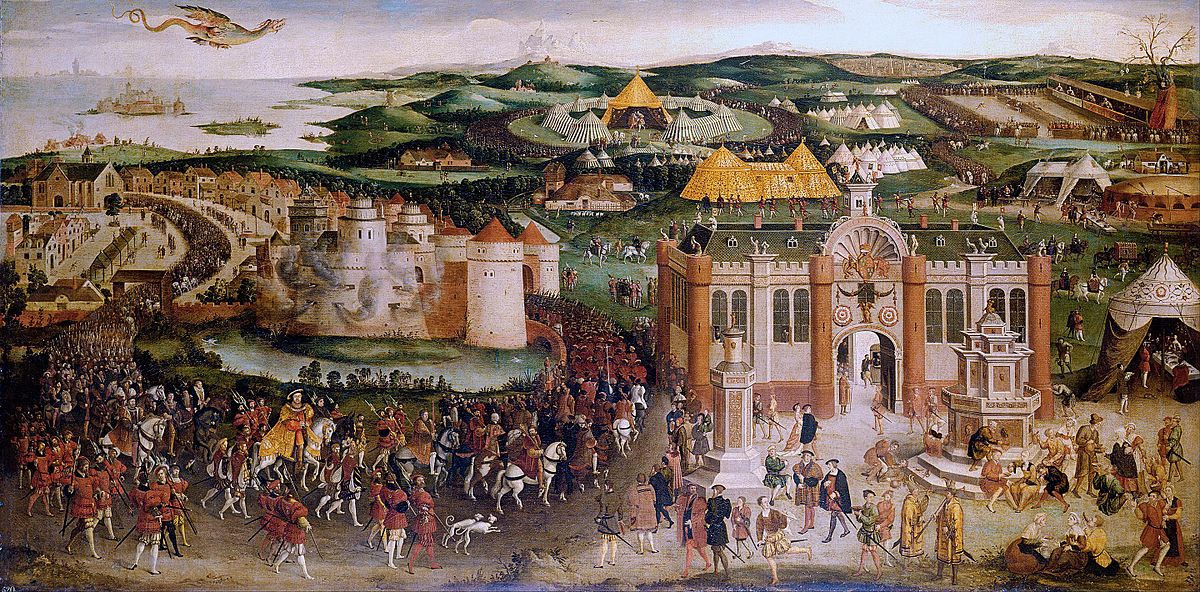

12 June 2020Five hundred years ago this week the monarchies of England and France met in the meadowland of the Pas-de-Calais. Today these flatlands are largely nondescript for the traffic that flashes past them on the A26, ‘l’Avenue des Anglais’, but even now the fields six kilometres to the east of Guînes, on the edge of the village of Balinghem, carry the sign ‘le camp du drap d’or’, or, changed somewhat in translation, the Field of the Cloth of Gold.

Here Henry VIII of England and François I of France, and the clerical and seigniorial hierarchies with which they governed, faced one another for a formal encounter that continued for a fortnight. It was the first meeting of these young monarchs – François was 26 and Henry was 29 – whose kingdoms had been in a state of war with one another for most of the past decade.

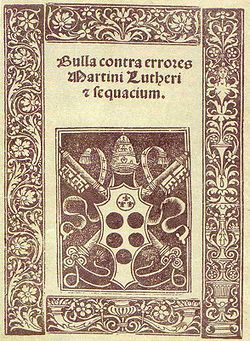

It was a conceived as a point of departure and certainly for François whose first years of rule had seen the successful extension of his military might beyond his borders, he surely anticipated this as the first stage on which he would be recognised unequivocally as a broker of Europe’s balance of power. Yet it was also the fulfilment of a rapprochement to which the ministers of both sides had applied themselves with serious purpose already for two years. At a diplomatic summit convened in London in October 1518 a pact pledging non-aggression had been agreed by the ambassadors of both kingdoms, and those of the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V and the Papal States. The rhetoric of this pact reached for a yet higher purpose, a universal peace for Christendom to protect its integrity from the advance of the Ottomans at its eastern frontier. But the realpolitik was the common imperative for a pause in the costly competition for continental overlordship. Money and conflict within the political nation were the inherited problems of the last late medieval rulers; now there was another threat, by June 1520 (when Martin Luther was the subject of the papal bull Exsurge domine) clearly focused on the horizon: a schism in the institutional church.

What both kingdoms hoped to carry away from le camp was something more than a pledge, a substantive treaty that might at least spare them from conflict on one of their frontiers. But common ground of such a pragmatic kind is rarely sufficient between ambitious heads of state to secure a settlement for the long term and their two-week interlude at their common border yielded no treaty. Rather, its tangible effect was to inscribe the self-image of the two reigns, still at the beginning of their course. This was a political summit performed as a pageant: in their trains, François and Henry paraded nobility, knighthood, prelates and clergy, the two presiding estates of their kingdoms; and the third, productive estate was a palpably present, in the hundreds of household staff attendant on each one of the principals, and in the machinery that supported them, manmade and land-raised, horses (for war and for carriage), hunting dogs and hawks.

The vast supporting cast was staged for presentation to either side with visual and aural accompaniment that self-consciously demonstrated the kingdoms’ claim to cutting-edge artistry. The choristers that performed with the English prelates wore the portcullis pattern vestments which Henry’s father, Henry VII, had provided for the Tudor family chantry – configured as a Lady chapel – at Westminster Abbey, new in 1520 and the costliest architectural and artistic project witnessed in living memory.

The pageant was an expression of the nations’ magnificence, but in the English party there was a painstaking effort to represent the regions of the Tudor kingdom. Here, perhaps, was an early indication of Henry’s notion of an imperial monarchy which would take shape over the next decade, as the leading lordships of provincial England were summoned to stand foursquare with their king. For the West Country, there were six delegates: Sir John Arundell and Sir Piers Edgcumbe representing the far west; John Bassett and John Bourchier standing for the north of the region (from Umberleigh to Bampton); Sir William Courtenay of Powderham and Henry Courtenay, earl of Devon, whose anchorhold was the region’s only city, Exeter, its estuary and its eastern march. Earl Henry, aged just about twenty-two, was already remarkably close to the centre of royal power and serving as a Gentleman of the Privy Chamber. Alone among the West Country men he was positioned in the principal royal train as they took the field at Guînes. A sequence of tournaments punctuated the programme there, and in the lists the earl excelled; he was one of the only English knights to emerge undefeated from each one of his jousts. His conspicuous prowess can only have further burnished the king’s favour and scarcely a year later he received a portion of the attainted lands of the Yorkist traitor, Edmund Stafford, duke of Buckingham. In 1525, Henry conferred on Courtenay the title of Marquess of Exeter.

The west of England still carries some trace of its part in the performance five hundred Junes ago: some of the personal archives of Earl Henry and Sir William Courtenay remain in the Powderham collection. At Berkeley Castle, there is a fabric fragment believed to be from one of the very tents that were pitched on the field.