Posted by James Gordon Clark

30 September 2020On 1 October 1536 a crowd of worshippers which had just spilled out from the parish church of St James at Louth (Lincs.) was stirred into shouts of angry protest at the Westminster government’s interference in their lives. Their cries included some of the familiar complaints of the pre-modern commons: that evil counsellors held the king in their clutches; that the policy of his government punished the many for the profit of the few; that the livelihood of loyal subjects was being drained away by levies that knew no precedent. But their anger also targeted a new theme: the government’s interventions in the institution of the church and customary religious practice. In particular, they expressed their fury at the forced closure of dozens of religious houses in their region under an act of parliament issued six months before. They had watched this compulsory suppression slowly but steadily advance across the county since the summer. Only now did they voice their reaction, encouraged by the general climate of agitation; and also by the presence among them of several professed canons and monks from monasteries nearby, including some of those whose houses had just been seized and their communities dispersed.

What followed the sudden outcry at Louth is very well known to historians. A band of laymen and clergy – canons and monks among them – hurriedly mustered and set off on a march to the cathedral city of Lincoln to win formal and public recognition for their cause. There, they stormed into the cathedral church and took armed control. Its chancellor was cut down in the melee. In just two days they were driven out, some killed, many captured. But their fury reverberated and in barely a week there were copycat uprisings north of the Humber. The reformation rebellion known as the Pilgrimage of Grace had begun.

The involvement of the religious orders in the Lincolnshire rising has long been debated. The principal primary sources are the statements of the captured rebels, which carry all the contradictions and self-conscious evasions of testimony taken under duress. There were certainly canons and monks in the crowd at Louth. Some of them joined the march to Lincoln. Among those taken, questioned and, in due course, executed were professed men from the Cistercian abbey at Louth and Kirkstead, the Benedictine abbey at Bardney and the Premonstratensian abbey at Barlings. The most consistent story taken from them when captured was of their being pressed to join the rebel band by force and under threat of violence to them and their houses. The statements of secular clergy and laymen captured with them told it differently: it was some of these monastics who had stirred the crowd. The men from Barlings in particular were remembered as prominent captains in the field.

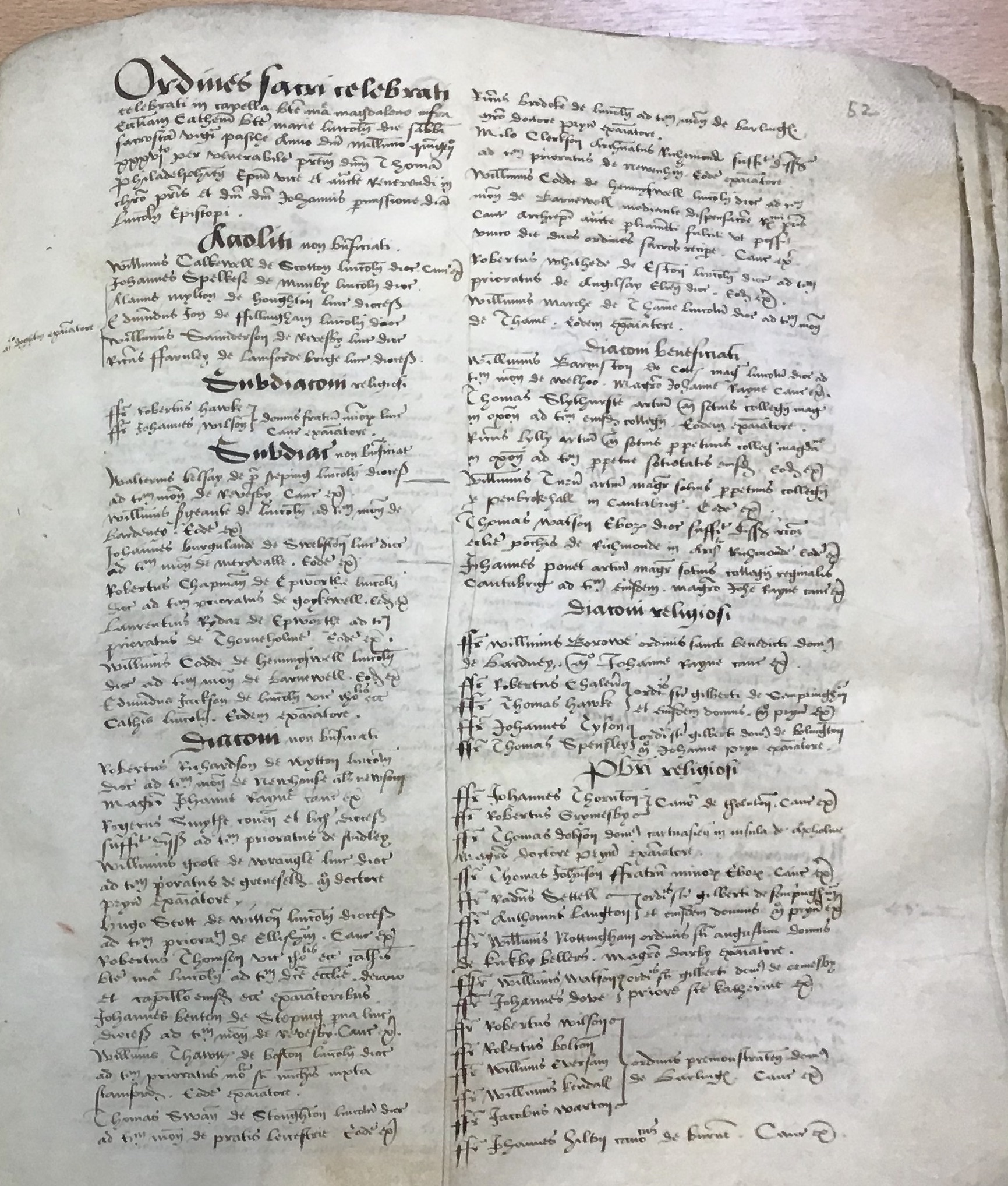

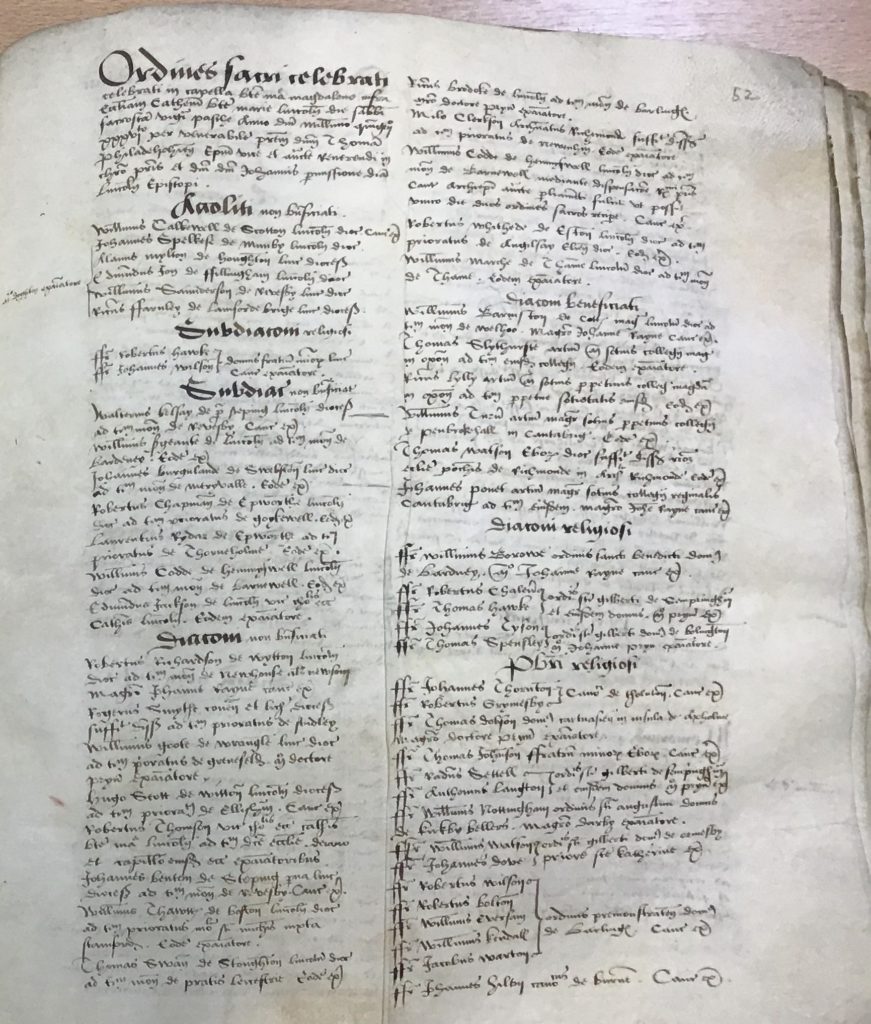

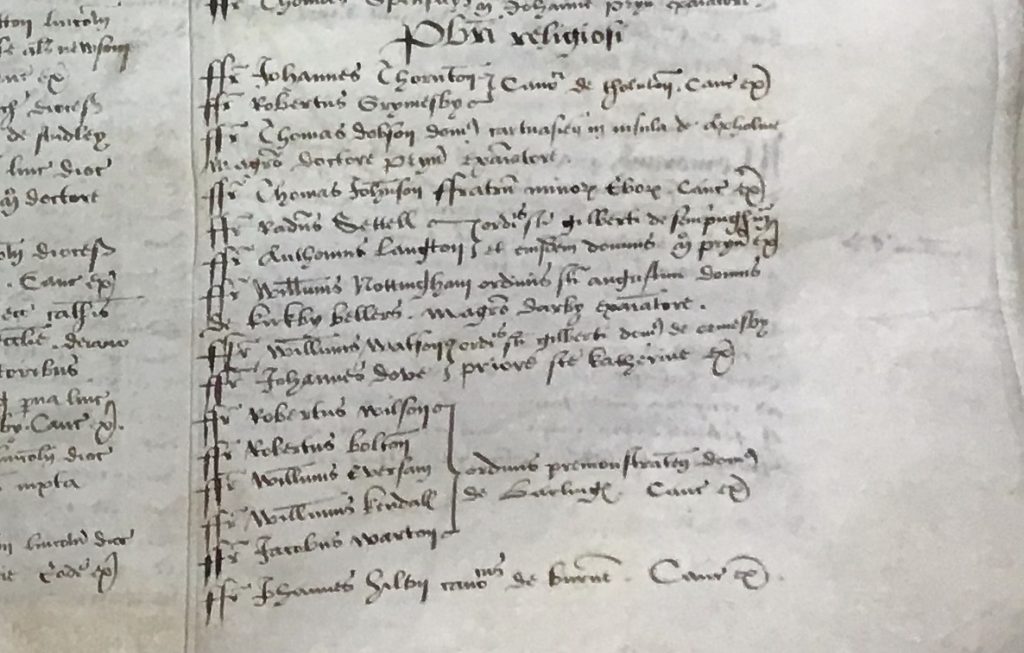

The witness statements say very little about these men except their names and in some cases their office in their monastery. Now, thanks to a neglected entry in the register of the Bishop of Lincoln, held in Lincolnshire Archives, it is possible to know a little more. Three of the canons from Barlings apprehended, and ultimately put to death for their part in the risings, appear standing together at an ordination ceremony in Magdalen chapel at Lincoln Cathedral just six months before. William Eversam, James Warton and William Kendall were presented as candidates for priesting at Easter 1536.

Their ordination to the priesthood on the same day provides several insights into their identity as canons. Monastic and mendicant candidates were progressed from minor orders to priesthood in cohorts, according to the timing of their initial entry into their house. By the sixteenth century, it was typical for priesting to coincide with the conclusion of the formal noviciate. The minimum age permitted under canon law to enter priest’s orders was twenty-four; for generations, religious houses had kept close to this minimum (and sometimes contravened it) because of their need for qualified priests. It may be safe to say that these three future rebels – executed as felons a year after their examination by the bishop’s suffragan – were newcomers to the religious life; young men; and they had been bound together for as long as they been at Barlings, because date of entry and placement in a cohort were the defining features of any monastic society.

Knowing this raises further thoughts about their involvement in the rising. They were a cohort, already confederates as they made their way as new canons of their community. They might have been pushed into the rebel band at the point of a pikestaff; but they might have made a collective decision to join it. They had lived together as novices, perhaps for eighteen months or more before that fateful October day. They knew each other’s mind. Certainly, they acted in defence of a way of life they had only just begun.

Their recent entry into the monastery and their (apparent) youth offers an important reminder about the state of the religious houses after the Henrician reformation was underway. In spite of the best efforts of the king’s commissioners, the monasteries and friaries continued to take in recruits. Ordination records show that incoming cohorts were still making their way in holy orders as much as three years after the Lincolnshire rising. The surrender deeds of the last monasteries standing in 1539-40 record the presence of novices who had not yet concluded their probationary term. The monastic estate that confronted the kings reformation, and in some locations resisted it to the death, included a rising generation, like the Barlings three, only just coverted to life in the cloister.