Posted by James Gordon Clark

29 October 2020Today, Tynemouth Priory (above) looks a likely place for a haunting. The ruin stands tall and gaunt at the high point of the windswept Northumberland coastline. Advancing towards its hollow east end is a wave of weathered gravestones. There was no gothic cemetery outside when it was a living community of monks (Benedictine) but the medieval residents may well have felt a chill over the burials within. This monastic church carried the macabre distinction of being, for a time, the resting-place of two murder victims, both of them monarchs: Oswine of Deira (d. 651), in whose name the church was dedicated; and Malcolm III. king of Scots (d. 1093).These monks were the custodians of spilled blood and stolen lives.

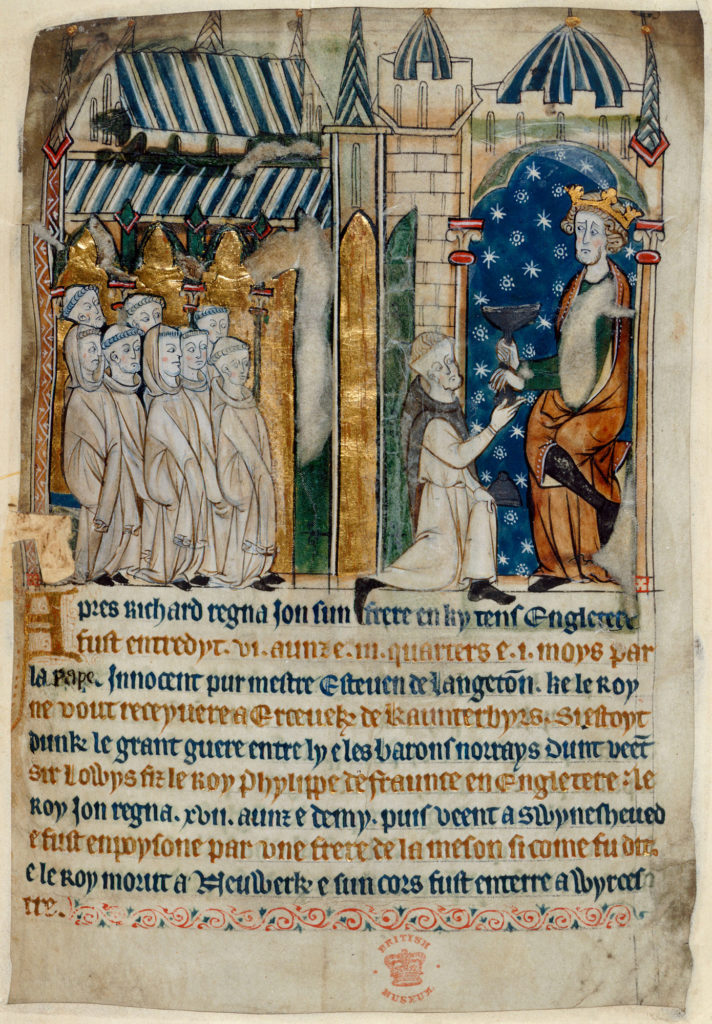

Perhaps it is no surprise then to find that Tynemouth was the scene of a unique medieval ghost story, recounted only by the thirteenth-century chronicler, Matthew Paris (d. c. 1259). One night in 1224, a monk, Reimund, awoke in his bed to see an apparition of King John (r. 1199-1216) standing before him. He was dressed like a king, in a robe ‘commonly called imperial’, Matthew says. Recalling that the king was dead, Reimund asked him, lamely, how was it with him. Worse than any man, the monarch replied, explaining that his robe was of an unbearable weight – more than any man of the living world might lift – and its imperial glitter was in fact a perpetual fire. Yet, he confided, he trusted in God that he might be released from his suffering by the intercessions of his son, Henry, his alms giving and his reverence for Christian worship. He has shown himself and his awful suffering to deliver a message, through this monastic community, to his old partner-in-crime, Richard Marsh, bishop of Durham (d. 1226), a prelate, by no coincidence, who was the avowed enemy of the monks of Tynemouth. Richard must be warned that his own seat in hell had been prepared, and he would surely take it soon unless he change his shameful ways, and did penance. The ghost then offered two proofs of his identity, one for the monk in front of him and one to be presented to the bishop: first, he described a ring which the king had given to the priory as a votive offering; then he related an instance when the bishop had counselled him on how to cheat the Cistercians of their year crop of wool. Then, he disappears.

Warnings from the domain of dead to the living world were not uncommon in medieval dream visions but this encounter has the different characteristics of a classic ghost story. Reimund is awake, and the ghost of John steps into his world; he even closes the distance between them by speaking of objects and people on the monk’s own horizon. Six hundred years before the publication of Dickens’ Christmas Carol (1843) this ghostly John seems to anticipate the character of Jacob Marley. Like Marley, John is a soul in torment; he too carries the burden he made for himself, the robe he wove in life. Bishop Richard is his Scrooge, albeit his heart is black, not merely cold.

Beyond Matthew, there is no other telling of this ghost story. But it is not the only story of apparitions associated with King John and his death at Newark Castle (Notts.).

The chronicle compiled at Coggeshall Abbey (Essex) remembered that the night of the king’s death – 18-19 October 1216 – was haunting indeed. In the middle of the night there was such a shattering wind and storm that the townspeople feared that their houses would fall. Many spoke of the horrific and supernatural apparitions (horribiles et phantasticae visiones) that came to them. By implication at least, they were terrifying, for the chronicler would not say what they were (hic describere supersedimus).

John had been sick for some weeks before he died. He had been campaigning across the middle of the kingdom, through Suffolk and Norfolk into Lincolnshire, and it is possible he succumbed to dysentery, the soldier’s disease. Yet stories soon circulated of suspicious circumstances. Before the end of the thirteenth-century, an Anglo-Norman verse chronicle (now BL MS Cotton Vitellius A XIII) had taken up a tale of John’s death being the result of a poisoned draught he had been given at Swineshead Abbey, where one of the monks had been determined to end his oppressions of the church. Half a century later in his Polychronicon, Ranulf Higden (d. 1364) had worked the story into a vivid vignette. While John still lived a portent was spoken that he would meet his end at Swineshead. The king responded with an oath that he would retaliate if he lived another year and raise the price of bread from a halfpenny to twelvepence. A lay brother of the house mixed a poisonous brew and coaxed him into drinking it. Higden relished the tale but also held it at arm’s length, offering it to his reader only after he had recorded that the king had died from dysentery.

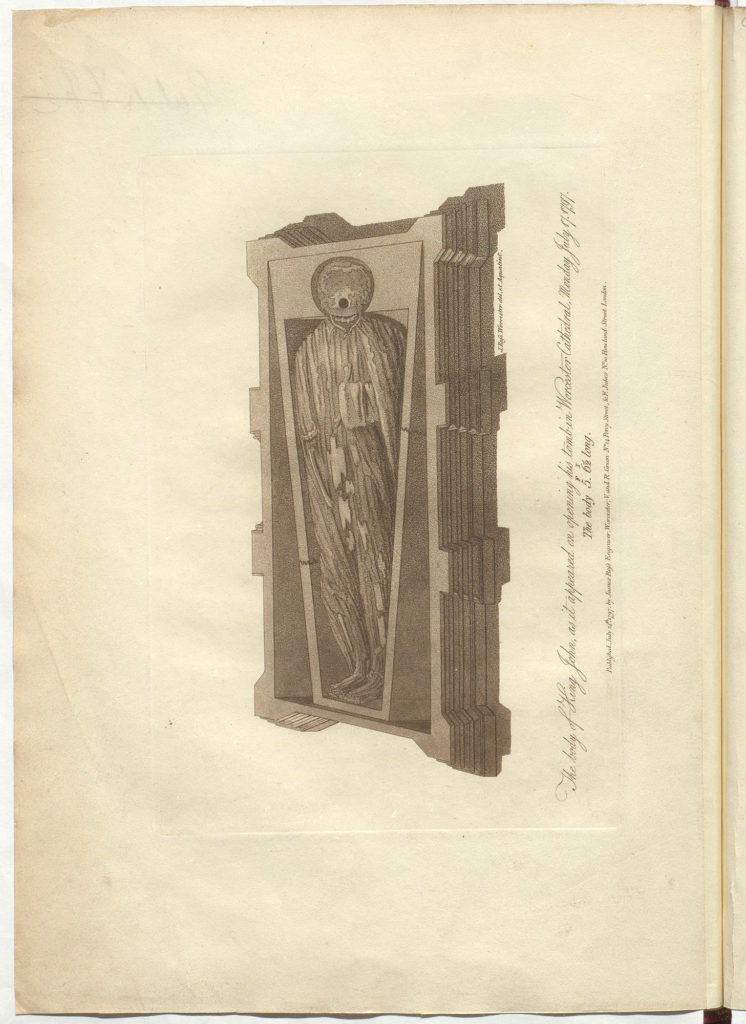

The macabre fascination with the dead King John was more than a literary trait. In 1239, scarcely a decade into his personal rule, his son Henry III went to his tomb at Worcester Cathedral to see the sarcophagus opened, to look in the face the father he had last seen as a boy of nine. Some 290 years later, the tomb was opened again, and the former Carmelite friar, Reformation provocateur and antiquarian, John Bale (1495-1563), described the sight in uncompromising detail in his commonplace book.

The encounter pressed on Bale’s imagination. In his play Kynge Johan, first written and performed around 1538, the eponymous subject is again represented as the victim of a conspiracy. Simon of Swynsett (i.e. Swineshead) offers him a ‘marvellous good pocyon…a better drink is not in Portugal or Spain’. At once the king is stricken, ‘my body me vexeth, I doubt much of a tympany’. John dies, declaring, ‘There is no malice to the malice of the clergy!’. Then, the final act of the play opens to the spectacle of a supernatural apparition, named as Imperyal Majestye. A spectre of John, or of England’s kingship itself? Whichever it is, he arrives to deliver judgment on the living. The persons of ‘Commynaltye’ and ‘Nobility’ are summoned, to know ‘Ye are much to blame’. ‘Thu playest such a wicked parte’, Majestye’s minister, Veryte, condemns them, warning ’…thy great parell and exceedynge ponnyshment’. He commands, ‘Bowe to Imperyall Majeste. Knele and axe pardon for yowr great enormyte’. Once again, John’s own death and his ghostly presence are pretexts for exposing the wickedness of the world.

The link between the legend of King John and ghostly apparitions was revived in the Victorian period. Martin Tupper (1810-89), philosopher and popular poet, created a new tale of a haunting in which John played a pivotal role. In his historical novel, Stephan Langton (1858), he narrated a story of the king’s abduction, abuse and murder of the daughter of a woodman living in the lee of the Surrey Downs south east of Guildford. John was said to have drowned the girl a spring-fed lake known as the Silent Pool. Ever after, her ghost may be seen at midnight rising from the middle of the pool. By the early 20th century, the Silent Pool had become a site of tourist interest.

King John’s reputation, the manner of his end and even his corrupted corpse have been an enduring source of inspiration for ghoulish reflections on life and death, good and evil, shaping the contemporary response to the traumas of his time, and still, post-medieval representations of that world.