Posted by Edward Mills

20 November 2020Being Human is an annual festival in celebration of the humanities, organised by the School of Advanced Studies at the University of London. Exeter’s medieval studies community has a history of organising engaging events for this wonderful project, including last year’s memorable guided tour of Exeter Cathedral; sadly, however, events such as this were no longer viable in 2020 as a result of the coronavirus pandemic. This didn’t stop the organisers of the festival, however, who this year worked around the clock to put in place a virtual series of events that captured the breadth of humanities research up and down the UK. At the time of publication, the festival is still ongoing, and can be explored further on its website.

For us at ‘Learning French in Medieval England‘, the online format of this year’s event proved both a challenge and a unique opportunity. Having originally planned to run a workshop on our project in-person as part of the festival, we found ourselves having to reconsider the format and scale of what we were preparing at fairly short notice, as our venue shifted from Exeter Central Library to … well, Zoom. In-person interactivity was suddenly off the table, and our original plan of using paper slips to give attendees a chance to do digital editing for themselves – an idea adapted from Dr. Charlotte Tupman and Dr. Elizabeth Williamson’s introductory XML sessions in our Digital Humanities Lab – had to be replaced with a new format that would be suitable for audiences at a distance, and from across the world. Our challenge, in short, was to give our diverse audience members – many of whom had never seen a medieval manuscript before, let alone considered how one might be edited – an introduction to questions of medieval textuality, digital scholarship, and critical editing.

Our solution was to seek help from a certain well-known boy wizard. Specifically, we opened the workshop by giving participants a lightly-adapted version of the opening lines to Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone, and asking them simply to copy it out by hand. What we didn’t tell them was that we had made a few subtle changes to the original text. Here’s our extract in full: how many can you spot? (Answers at the bottom of the page.)

Medievalists reading this page will likely have realised the point behind this exercise: the ‘errors’ that we introduced into the Harry Potter text in fact reflect many of the alterations that medieval texts underwent during the scribal copying process, from unwitting metathesis (alterations in word or letter order) to deliberate acts of editorial intervention. There was, of course, no single ‘right’ way for our participants to copy out the extract, and some participants retained the changes that we’d made, while others adapted them (most notably seen in the minority of participants who underlined the passage that was italicised) and others still simply ‘corrected’ them. In choosing a text that many audience members would be familiar with, we’d hoped to elicit precisely this range of responses, and we were thrilled to see how fascinated participants were as they came to realise the sheer range of decisions, both conscious and subconscious, that are made when copying a text by hand.

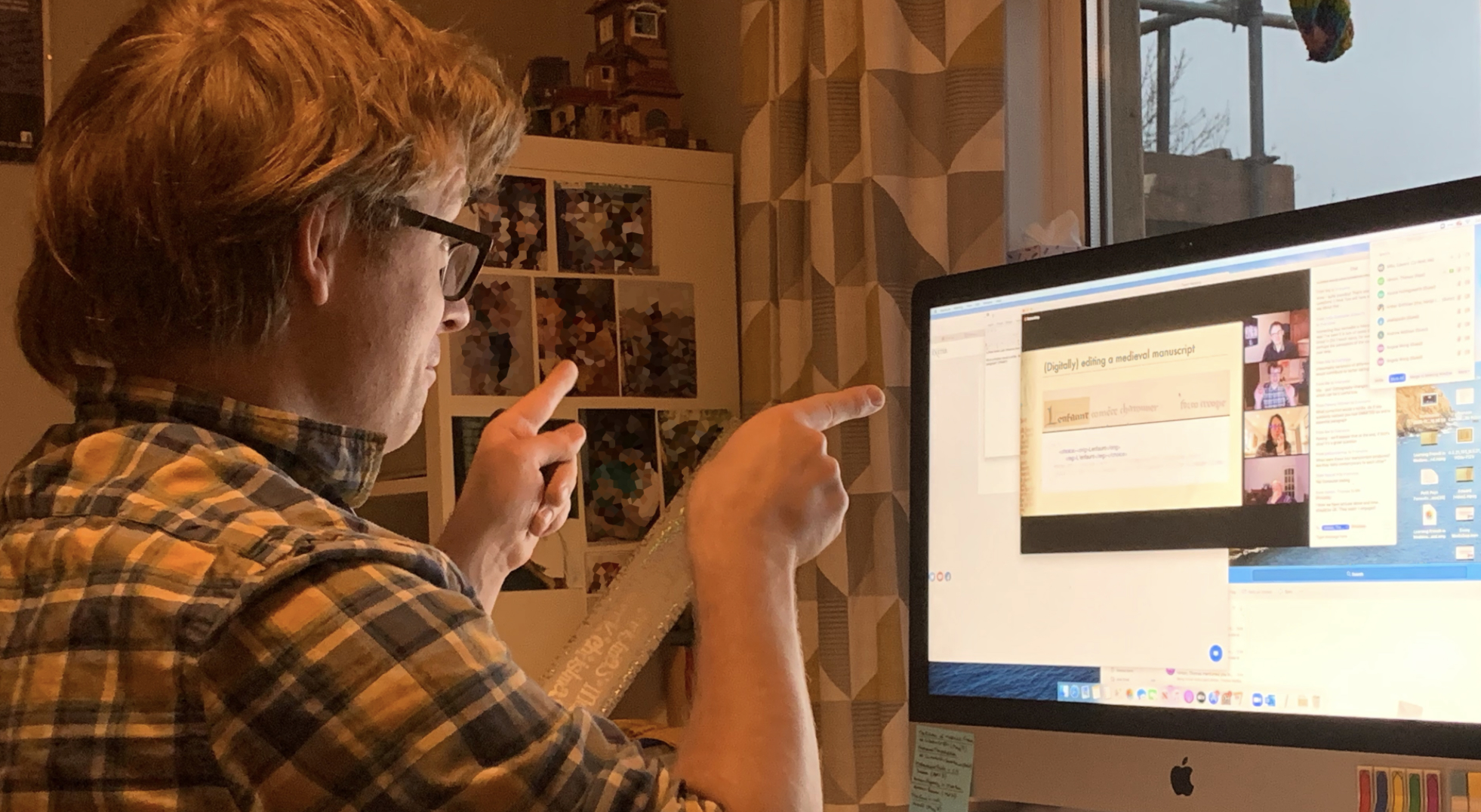

Of course, many of the key elements of our one-hour workshop didn’t require such a drastic degree of alteration for online delivery. Tom Hinton’s introduction to the editorial history of the Tretiz, and to critical editions more generally, provoked a great deal of interest, as did our joint exploration of how medieval manuscripts are represented in popular culture (via Disney films, Shrek, and notions of parody). Most excitingly, however, the online-only format allowed us to massively expand the capacity of the event, and we were delighted to welcome over eighty attendees from around the world. The event also generated a considerable amount of interest on Twitter, as you can see from the selection of Tweets provided below. A video recording of the event is available to watch in full on Vimeo.

Learning French in Medieval England is an AHRC-funded project at the University of Exeter’s Department of Modern Languages, and aims to produce the first digital critical edition of all extant manuscripts to Walter de Bibbesworth’s thirteenth-century rhyming French vocabulary, the Tretiz. More information about the project is available on its website and Twitter page; earlier blogs from project members are available here, here, here (external link), and here.

Full stop after ‘Mrs.’ removed, ‘Drive’ un-capitalised (l. 1); italics added to ‘thank you very much’ (ll. 2-3); ‘involved’ respelled to ‘invovled’, comma replaced with semicolon (l. 4); word order altered, with ‘just didn’t hold’ becoming ‘didn’t just hold’ (l. 5). Many other variants were also introduced, of course, most notably surrounding line-breaks (most did not respect line-breaks after ‘were’, ‘you’, and so on), the colour of the ‘ink’ (we’d chosen brown), and letter-forms (understandably, almost no-one attempted to replicate the distinctive shape of 16pt Arial).