Posted by James Gordon Clark

31 December 2020As the present benefits of study abroad (and the Erasmus programme in particular) are in the spotlight, it is worth considering a past example: a beautiful manuscript book copied and annotated by an English student at Ferrara in 1460 where he was taking a break from his degree course at his home university to attend classes in Latin rhetoric taught there by the leading master of the day.

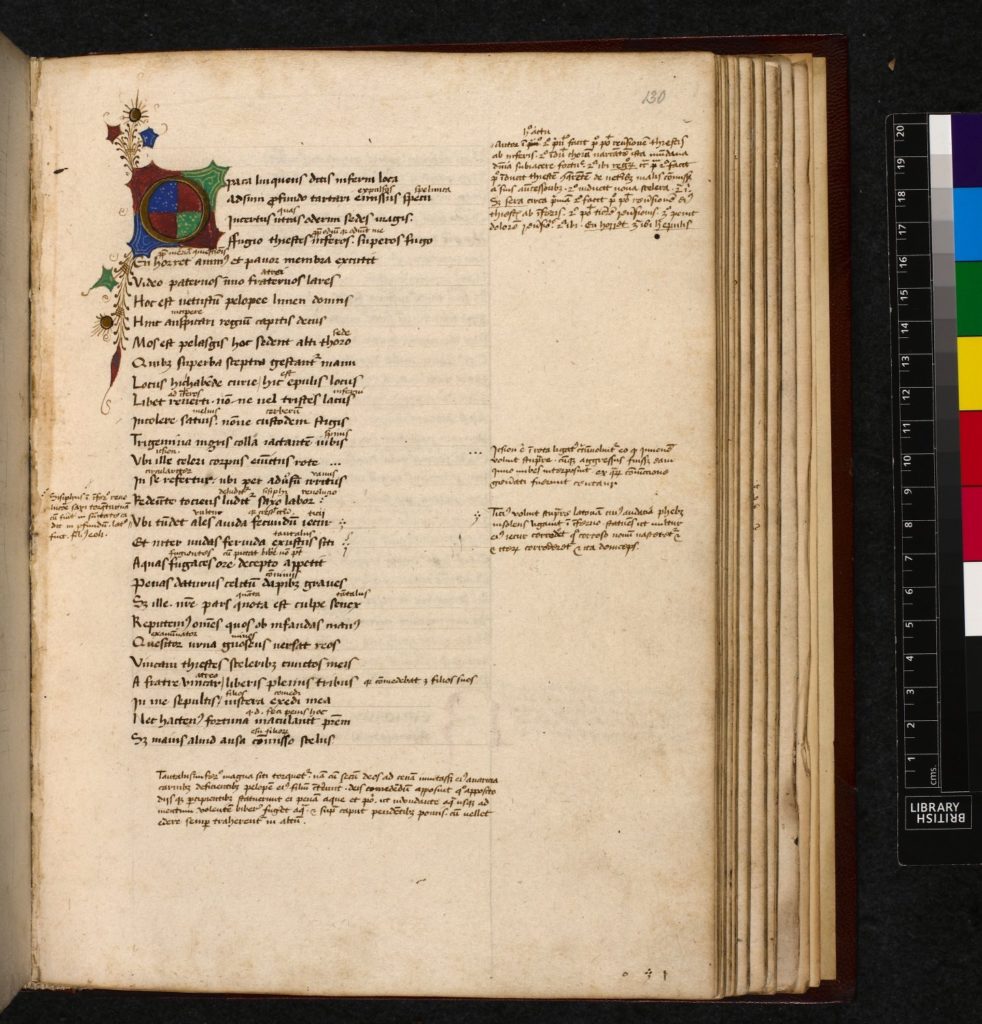

The book (now, British Library MS Harley 2485) contained the texts of the Seneca the Younger’s Tragedies, works especially valued by readers and writers with an enthusiasm for classical culture, as a template for the dramatic art and a treasury of ancient myth. Complete copies were rarely seen in England and it is no surprise that finding an exemplar was a priority for this student visitor on arrival in Italy. He was John Gunthorpe, who had come to Ferrara directly after completing the arts course at Cambridge.

His formal purpose was to follow the lecture course of Guarino da Verona, Ferrara’s most acclaimed professor, an authority both on classical Latin auctores such as Persius, Seneca’s contemporary and fellow stoic, and on Greek: at this date such expertise was scarce in England.

It was another thirty years before the teaching of Greek was available to students within Cambridge or Oxford. Although Gunthorpe cannot have known it, this year was to be the last performance of Guarino’s lectures. He died in the city on 14 December 1460.

English students had pursued periods of study in the principal schools of mainland Europe from the first moment they had developed a settled pattern of teaching. Three quarters of a century before the Paris schools found formal recognition as a university (1215), John of Salisbury – then about the same age as Gunthorpe at Ferrara – had gone there to study theology under the celebrated master, Gilbert of Poitiers.

As university institutions grew, their faculties formed and their syllabuses formalised, it became increasingly common for the English to travel in the course of their student careers. Like John of Salisbury in the twelfth century, as much as John Gunthorpe in the fifteenth century, generally they turned to the mainland at the end of their initial training in arts, to lay the foundations for advanced study, as postgraduates.

The greater size, space and status of Paris in the thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries proved a powerful draw. For England’s student monks and regular canons there was also the compelling practical consideration that dedicated houses-of-study for members of their orders were established there long before they were set up at England’s universities. Even after they acquired their own college at Oxford, the student monks of Christ Church Priory, Canterbury continued to take periods of study at Paris. There were Canterbury students there in the shadow of the Dissolution itself.

English students also responded to the European universities’ disciplinary specialisation. If Paris was pre-eminent in theology, Bologna was the obvious destination for those intending to study in either of the laws, canon and civil. From the early fourteenth century English lawyers also spent time at Orléans, the status of which was raised by the patronage of two canonist popes, Boniface VIII and Clement V. While the English crown governed Gascony, students of the theology also passed through Toulouse, the city where the presiding genius of their syllabus, the Angelic Doctor Thomas Aquinas, lay buried.

By the middle years of the fifteenth century, the commitment of the northern Italian universities to a classicised curriculum attracted English students also to Ferrara, Florence, Padua, Pavia and Siena.

The typical periods of undergraduate and postgraduate study were lengthy, and, to fulfil the formal degree requirements might take as much as fifteen years. It followed then that the time spent in study abroad was rarely less than one academic year. By the fifteenth century English students stayed in the academic communities at Bologna long enough to be chosen to be rector of their constituency of scholars which were organised into national groups, called ‘nations’. Gunthorpe cut short his time at Ferrara only because of Guarino’s death; he remained at his studies in Italy for another five years.

Despite their continuing institutional development, and the rise within them of self-governing college foundations, the late medieval universities remained receptive to such international student traffic. There can be no doubt that the opportunity was dependent on the means of the individual: after Ferrara Gunthorpe continued his studies in Italy because he found employment in the papacy and, ultimately, secured the valuable preferment of a papal chaplaincy. Those Englishmen known to have stayed at European universities long enough to have held rectorships were from well-funded gentry families: Reynold Chichele, Ferrara’s rector of Ultramontane scholars in 1448-9, was no less than the great-nephew of the archbishop of Canterbury.

Still, it may be that it was gainful employment rather than the advantages of birth that was the passport to study abroad. It was possible for the least well-connected clerks, those at the opposite end of the career track to Rector Reynold, to aspire to be a visiting student. As the incumbent of a parish benefice, they might apply for a licence to absent themselves for a period of years to study at a university or another studium supported by the income of their own living. Ralph Hyckys, rector of Calstock (Cornwall), received licence in 1435 for a two-year leave of absence to pursue his studies in canon law at Rome.

The return on such investment in study abroad was both intellectual – as Gunthorpe’s book bears witness – and professional. After his years of study in Italy he soon picked up royal patronage; in 1466 he was appointed chaplain to Edward IV; he then served as his almoner and under his brother, Richard III, he was Keeper of the Privy Seal. He was not displaced at the Tudor succession and in 1485 he was appointed dean of Wells Cathedral. Ralph Hyckys also found his own reward for his perseverance at canon law, securing a second parish church living at Phillack in the far west of the county.

James Clark