Posted by James Gordon Clark

24 September 2021Just when Lockdown 1 began I’d started to think about the acknowledgements I would include at the front of my new book, The Dissolution of the Monasteries. A New History. Already I had a long list of names in mind.

Then the implications of a complete suspension of research life became clear. Campus and library were closed, and for long weeks there was no prospect of access to the office where I keep most of my academic books. Now I faced the task of completing the final edit of the book and finding 30+ illustrations with all of the usual resources – British Library and its imaging studio, National Archives, regional archives, Inter-library Loan – shut down for the foreseeable future.

I’ve lost count of the times over this past year that well-meaning people have said to me: ‘Of course, for the kind of research you do, I imagine it’s not so bad because pretty much everything you need is online!’. Er, pretty much not, in fact. Even the medievalist with an interest in Britain’s abbeys, cathedrals and other well-documented foundations will find that open-access sources are thin on the ground, despite the best efforts of Internet Archive to dig up long-forgotten nineteenth-century editions.

But what is free-to-access online is an extraordinary community: even via organisations’ official homepages and, of course, Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, personal blog sites and good, old-fashioned email. As all the familiar avenues remained closed off my relationship with this virtual network was steadily transformed.

Now that the long disruption to research facilities is coming to an end, and a visit to the BL promises to be a little less like buying a ticket to the Glastonbury Festival, it is worth marking how the virtual world has helped research to carry on.

I was able to reach archivists at city and county heritage centres – for example, London Metropolitan; Hereford – who were only too glad to lift the gloom of their reader-free search rooms for a moment to snatch a phone image of that one Dissolution deed I’d been counting on before research facilities were closed off.

Contact through the homepage of the Isle of Man Natural History & Antiquarian Society connected me to the intrepid Dave, whose DM told me he would take advantage of the empty roads to catch the last mail plane of the day to be sure that hard-to-find monograph on Rushen Abbey (Mannishter Rushen) – the last Cistercian house of all to fall (in June 1540) – was in my hands by the next day. Parcelforce presented it to me the next morning at 10am.

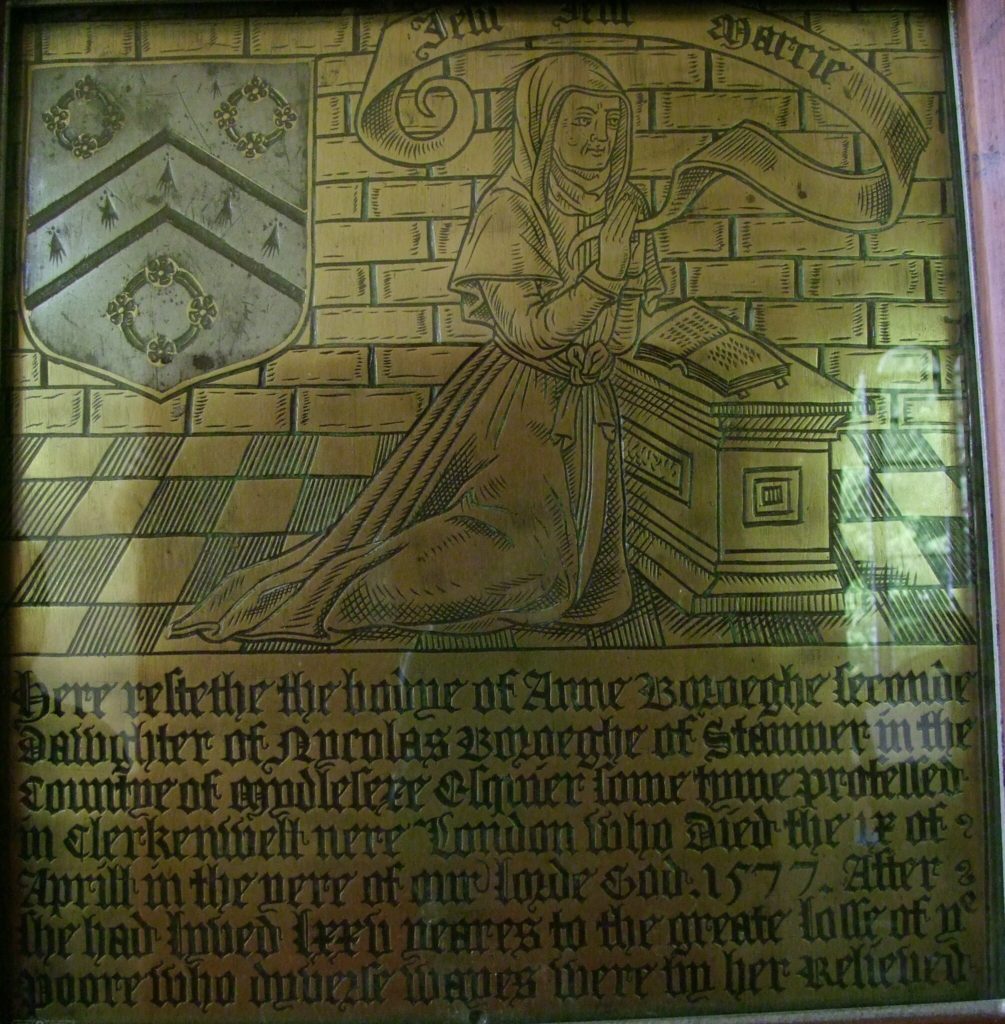

The lively virtual noticeboard of the tiny village of Dingley, Northamptonshire (a population of 194) put me in touch with Tony, keyholder of All Saints parish church, who generously agreed to redirect his one permitted period of outdoor exercise, open up the building and capture in close-up the beautiful memorial brass of Ann Boroeghe, former nun of St Mary’s Priory, Clerkenwell. She settled there after the Dissolution, apparently attracted by traditional sympathies of the new proprietor of the old Hospitaller Preceptory nearby.

Parish churches scarcely had a chance to consider even a partial reopening before Lockdown 3 but a post on the Vicar’s page of St Peter and St Paul, Dagenham, brought another against-the-odds plan from the verger, Steve, to follow the maintenance men into the building to take some fine IPhone images of the Urswick family brass, which, perhaps uniquely, shows the eldest daughter at the head of her sisters, in the habit of her nun’s profession. The patriarch, Sir Thomas Urswick (d. 1479), was Recorder of London and Chief Baron of the Exchequer and father of thirteen.

These ‘drop-everything’ responses and publication-standard photos were far more than I expected; and then I stepped into the middle of another network: Flickr. Of course, Flickr’s members are instinctive illustrators: they document their professional and personal lives in picture albums. They also like to show and share their talents. From across the community, they responded rapidly to my strange requests for very specific viewpoints of this gatehouse and that tomb effigy with wonderful images that spoiled me for choice. Very soon, the book’s illustration slots were all filled; and the quality was immeasurably raised. The last plate of all in the book is a Flickr close-up of the cadaver image of William Weston, Prior of the Hospitaller’s principal priory at Clerkenwell, the last leader of the medieval religious orders to be toppled by crown. It was said that he died on the very day that the congregation’s properties were seized by parliamentary statute.

My research address book and browser bookmarks are a good deal more diverse than they were twelve months ago. The book is about to appear (publication date, 12 October). The acknowledgements page has more than doubled in length. Research of this kind can continue under pandemic conditions, but like so much of life in Lockdown, it is a matter of people, not things.

2 responses to “The Upside of Virtual Research”

I can’t wait to get my own copy of James’s book. It promises to say goodbye to ‘the last degenerate years of the monasteries in England’ [Eileen Power] and to provide a fresh and complex analysis of the religious houses in their final period. In addition, when the fuel runs out and the supermarket shelves are empty, James is clearly the man to turn to for ideas on how to surmount any obstacle and get things done!

I can’t wait to get my own copy of James’s book. It promises to say goodbye to ‘the last degenerate years of the monasteries in England’ [Eileen Power] and to provide a fresh and complex analysis of the religious houses in their final period. In addition, when the fuel runs out and the supermarket shelves are empty, James is clearly the man to turn to for ideas on how to surmount any obstacle and get things done!