Posted by James Gordon Clark

1 March 2022The Douce manuscripts and printed books, held in Oxford’s Bodleian Library, are one of the most remarkable medieval collections to have been put together by a single bibliophile. In the first place the collection is striking simply because of its date: Francis Douce (1757-1834) found these 420 medieval books on the open market in the decades either side of 1800. It is astonishing to think that so many British and European codices and early imprints should have remained in circulation outside the leading libraries some three centuries after the Reformation. The collection is also unusual for its exceptional examples of scribal skill and decorative art. Douce recovered the Ormesby Psalter, perhaps the finest of all the extant service books written and decorated in late medieval England, which was a source of inspiration for the Pre-Raphaelites, William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones; and the Apocalypse now named after him (MS Douce 180), which may have been the commission of the Plantagenet royal family, initiated by Henry III (1216-72) and completed by his son, Edward I (1272-1307).

Yet the books are equally fascinating for what they reveal of the research interests of Francis Douce himself. He set out to collect manuscripts and early print that could illustrate the ‘manners, customs and beliefs’ of the people of the Middle Ages. He was drawn especially to imaginative literature and to the images and texts that reflected, as he understood it, popular religious beliefs and customs.

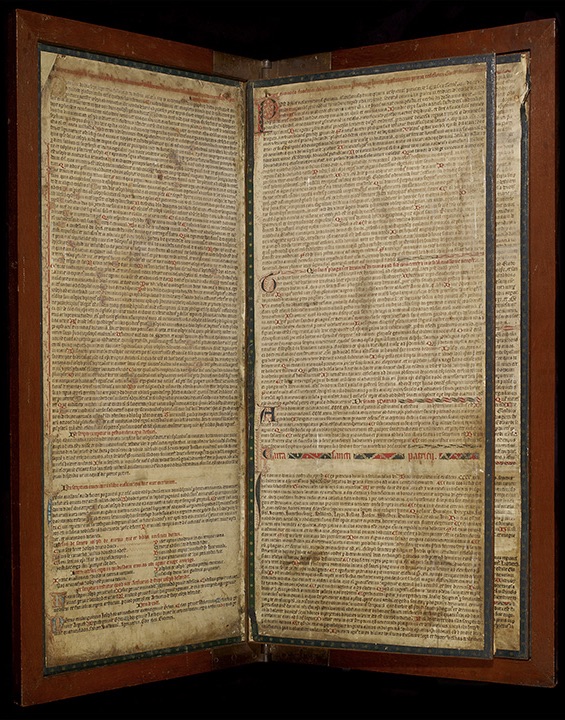

Douce MS 270 is a rare example of a medieval book which can be fixed very precisely in time and place. On the verso of its second front flyleaf is a French inscription ‘Lan del encarnation nostre seignur M C XCVII le ior de la tephaine furent sor le fiertre saint Cuthbert’, which would seem to locate the book at Durham Cathedral Priory, which held the relics of St Cuthbert, at the time of Epiphany (6 January) 1197/98. The book contains a copy of the Latin sermons of Maurice of Sully, bishop of Paris (1160-96), and is fronted by a liturgical calendar originally written to record the feast days celebrated at Durham.

But the book is rarer still because it can also be connected to another time and place far distant from this great cathedral of the north. The calendar carries annotations, in scripts dating from the thirteenth to the late fourteenth centuries, which then locate the book in the West Country. Within three quarters of a century of that January day in reign of Richard I (1189-99), the book had travelled more than three hundred miles south to Somerset. There, it was in the possession of priests connected with the parishes of Kingsbury Episcopi and South Petherton.

The obits – calendar dates of death – of the incumbents of these churches were now entered into the old Durham calendar.

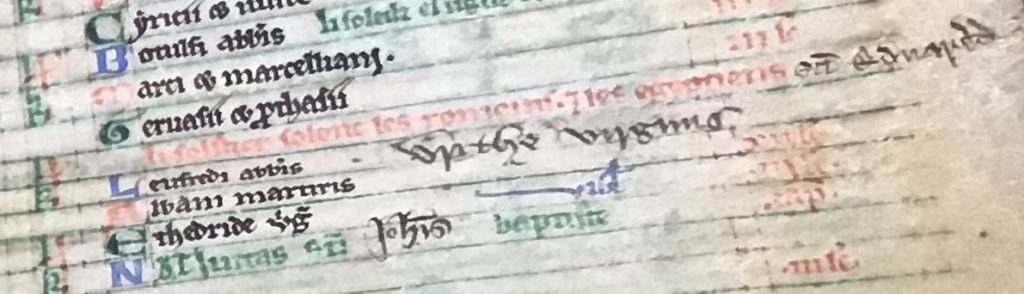

Also added were the feast days of saints whose cults were known almost exclusively in the South-West of England. One was the Celtic St Petroc, evangelist of Devon and Cornwall, whose cult was well-established in the region long before the Norman Conquest. The others were Anglo-Saxon, the royal sibling saints, Edith of Wilton (d. 984×987) and Edward, king and martyr (d. 978); and Urith of Chittlehampton (North Devon) whose shadowy story of martyrdom may stem from the eighth century.

The appearance of Urith’s name in the calendar is especially eye-catching. Interestingly the muddled annotator has entered her name on the wrong page, on the 8 Kalends of July (24 June) rather than 8 July, the feast day itself. Clearly, they knew the feast day but slipped up in handling this stained and rubbed calendar that was already two hundred years old.

The cult centre was the church of Chittlehampton, five miles west of South Molton. The feast day is also recorded in a surviving calendar from Tawstock, a little over seven miles away from Chittlehampton but not in those that survive from any greater distance such as Pilton, near Barnstaple, or Buckland, near Tavistock.

There are only fragments of evidence suggesting knowledge of Urith and her cult in Somerset. The remains of two prayers to the saint appear in a fifteenth-century anthology compiled by a monk of Glastonbury (Cambridge, Trinity College MS O 9 38); Urith’s image is found in stained glass at St Mary’s parish church at Nettlecombe on the eastern edge of Exmoor.

Now, the Douce calendar shows that her name also reached into the south east of the county, not far from the Dorset border.

The attachment of the clergy and people of parishes in Somerset to these saints as late as the fourteenth century is valuable evidence of the presence and persistence of the oldest English cults. It may be the result of the continuing commitment of the region’s monasteries. The women of Shaftesbury Abbey still processed the relics of Edward the Martyr in the sixteenth century, a commitment recorded in the Valor ecclesiasticus (1535). Their Benedictine sisters at Wilton Abbey made a new English history of Edith, their patron saint, in c.1420, for ‘For mony a meracle he hathe seythe ywrouht’ although they worried ‘For nomon nyl leve no meracle now’. The calendar of the Benedictines of Muchelney Abbey was marked with each of these saints except Urith.

Perhaps most influential of all was Glastonbury itself. The famous ‘Magna Tabula‘, a display panel describing the Celtic and Saxon saints whose relics and histories were preserved at the abbey, presents each one of the Saxon names found in the Douce calendar. It is very plausible that the priests from Kingsbury and South Petherton who took possession of the book had passed through Glastonbury and had seen the Magna Tabula and learned its legends for themselves.