Posted by James Gordon Clark

22 December 2022The relationship between a mother and a teenage daughter is often represented as inherently volatile. It has a long history as a trope in drama and fiction and in spite of a heightened awareness of, and suspicion towards facile stereotype it still surfaces today.

For the historian of more-or-less any time period and place before the past century, of course it is very difficult to cut through these representations to discover the lived experience of women, of their personal ties, to family members or to anyone else on their horizons.

Beyond the exemplary stories of preachers and guides to social behaviour and values also generated by the clerical establishment, medievalists often confront a complete void. Direct accounts of women acting in their family context are scarce. Rarer still is any record of their personal relationships expressed in their own words.

In an English context, really the only resource is the handful of letters found in the collections of a select group of elite families dating from the century before the Tudor Reformation. The correspondence of the family groups of Pastons, Plumptons and Lisles preserves brief but valuable glimpses of women acting and reacting as parents (and grandparents), children, siblings and spouses.

Here there are scarcely any sole exchanges between women – mother, grandmother, daughter, daughter-in-law – and most – as might be expected given what is known of changing patterns of language use, literacy and household administration – come at the end of the period.

A letter discovered in the Courtenay archive at Powderham Castle now casts some fresh light on this still elusive aspect of womens’ lives.

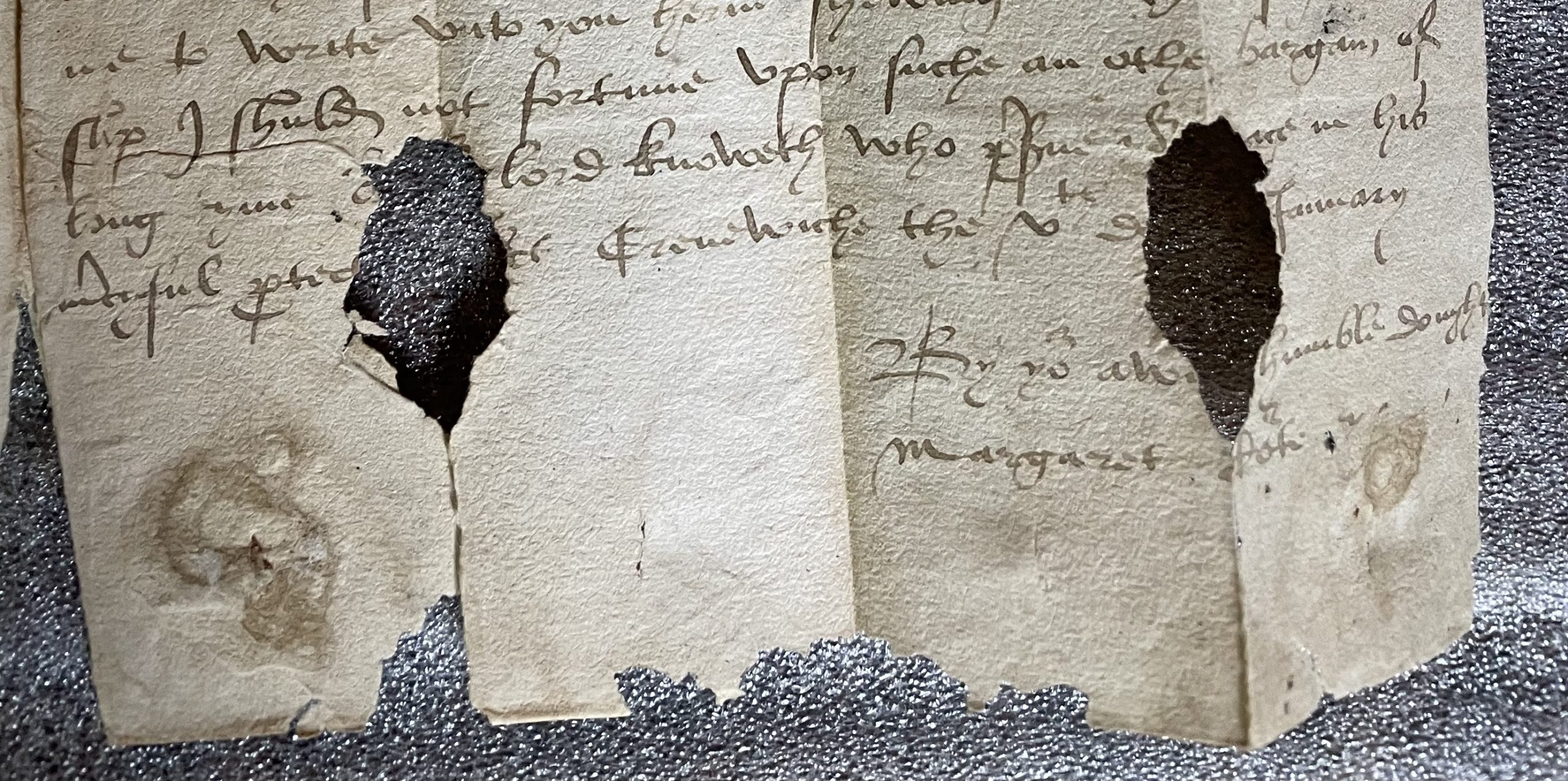

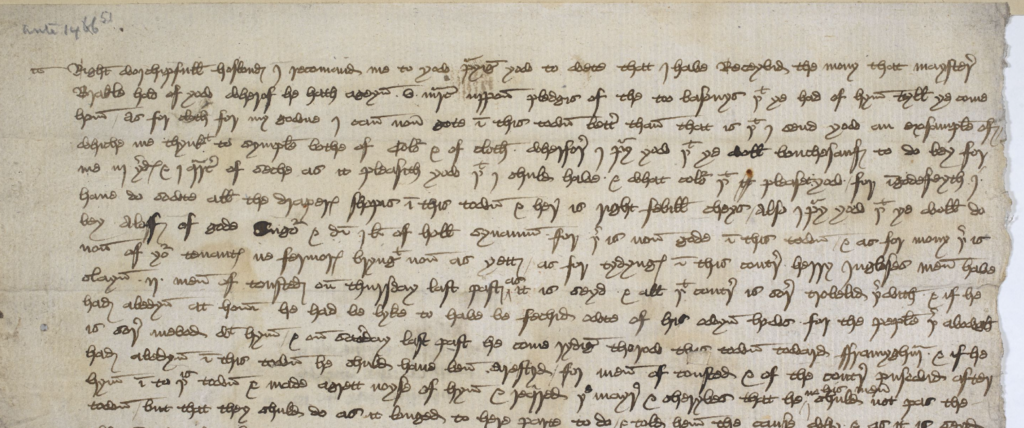

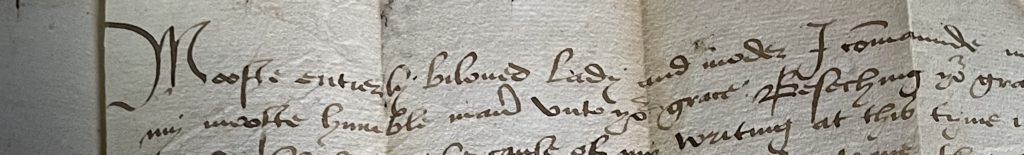

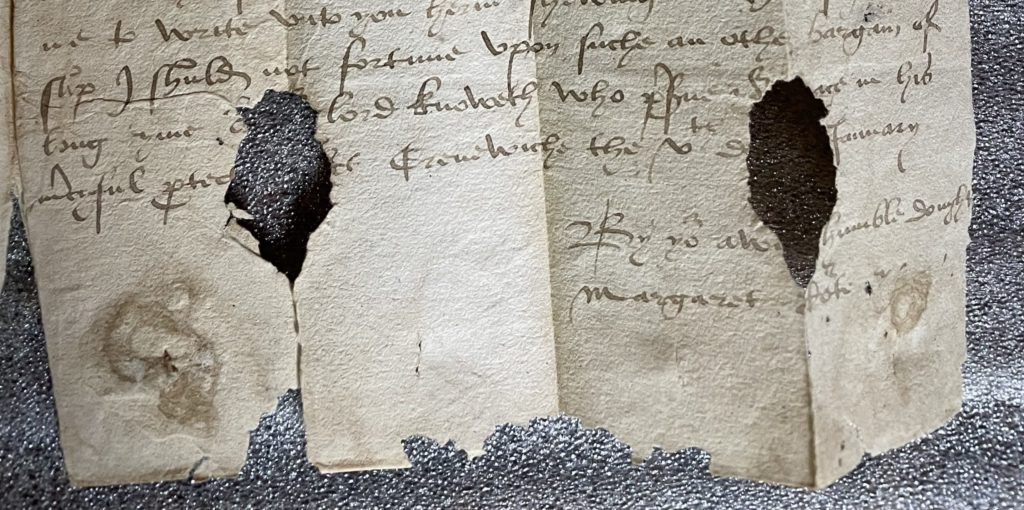

The letter, written in a clerical hand on a small, folded sheet of paper, has the appearance of an original not a fair-copy. It was sent by Margaret Courtenay to her ‘moste entirely biloved lady and moder’, Katharine, dowager countess of Devon. It carries a date of 5 January but gives no year. It can probably be placed between 1512 and 1514, since Margaret refers to the death of her grandfather, Edward Courtenay, earl of Devon, which occurred in 1512, and she signs herself with the family name she retained until her marriage in 1514.

When she composed the letter, Margaret was about the age of fourteen or fifteen. Her year of birth is not recorded but she was the youngest of her mother’s three children, her two elder brothers having been born in about 1496 and 1497 respectively.

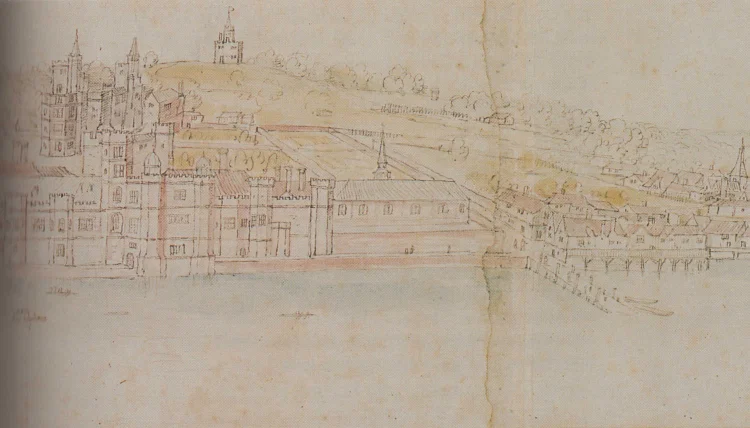

At the time of writing already Margaret had left her mother’s household. Her letter is placed ‘at Greenwich’, surely an indication that she was at court, among the throng of acknowledged favourites and hopefuls attendant on the young (twenty-three year old) Henry VIII) at the riverside palace that was the mainstay of the royal household.

Like (m)any teenagers, in her short letter to her mother Margaret passes through a spectrum of rhetorical – and, it might be said, emotional – positions, rebuke, request, plea for sympathy and at the last a play on parental pride and reputation.

Firstly, she complains that the terms of her grandfather’s will have not been honoured, a fault for which she holds her mother directly responsible. ‘Be so good lady and moder unto me that I may have my money of my lord my grandfaders bequest which is L [i.e. 50] marks by yere whereof sithens [i.e. since] his decesse I had never but £20’.

Then, she begs her to pay her the money which is her due. ‘Ye and your counsel wol calle upon thexcecutors to see that I may content of the hole’.

Next, she gives a glimpse of a most pathetic plight, trading clothes and jewels with fine ladies of the court who pity her. ‘I have made a bargain…for certen stuffe and jewels which lately were Lady Lisles whiche will drawe nigh C marks…I doubte not if your grace saw the penyworthes therof ye wold help me therunto’.

Finally, she needles her with the threat of public embarassment: ‘ther be diverse aboute the quene [i.e. Katharine of Aragon] that love your grace right wel councelled me to write unto you herin’.

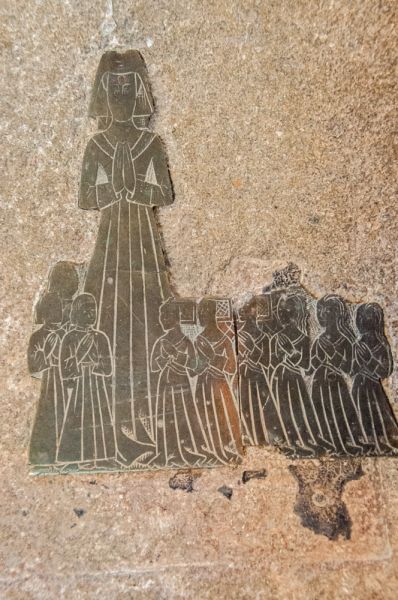

Margaret’s desperation was surely shaped by the formidable figure of her mother, Katherine. She was the dowager countess, who at the time of her daughter’s letter still held the lion’s share of her husband’s remaining property as her eldest son had not yet come of age. Also, she was of royal blood, albeit that of the displaced Yorkist dynasty. Daughter of Edward IV, she identified herself as the daughter, sister and aunt of kings.

Katherine’s own early life had been far from secure: the security of her royal lineage became a liability when Henry Tudor took the throne in August 1485. Ten years later, at the age of sixteen King Henry had married her to a hero of the Bosworth battlefield, William Courtenay, son of Earl Edward. But in 1502 Courtenay was implicated in the conspiracy to challenge the Tudor succession with the last Yorkist claimant Edmund de la Pole. William was imprisoned in the Tower of London and his lands placed under attainder (the suspension of any claim on property which was taken into the custody of the crown). When Katherine’s sister, Queen Elizabeth of York, died in 1503, her remaining security in the Tudor regime was lost, and she was no longer accepted at court. William was not released until Henry VIII’s accession in April 1509 and even then, his position and prospect of the restoration of his property remained uncertain. He lived only another two years, and months later his father also died.

The deaths of her husband and father-in-law opened a narrow window of opportunity for Katherine, providing her with substantial property and income until the succession of her son. The old Earl Edward had been generous in his will to his grandchildren, but so early in the reign of Henry VIII, there can be little doubt Katherine’s first instinct was to hold his inheritance jealously to herself. There is no other record of Margaret’s early life but this letter suggests her mother had dispatched her to find her fortune at court.

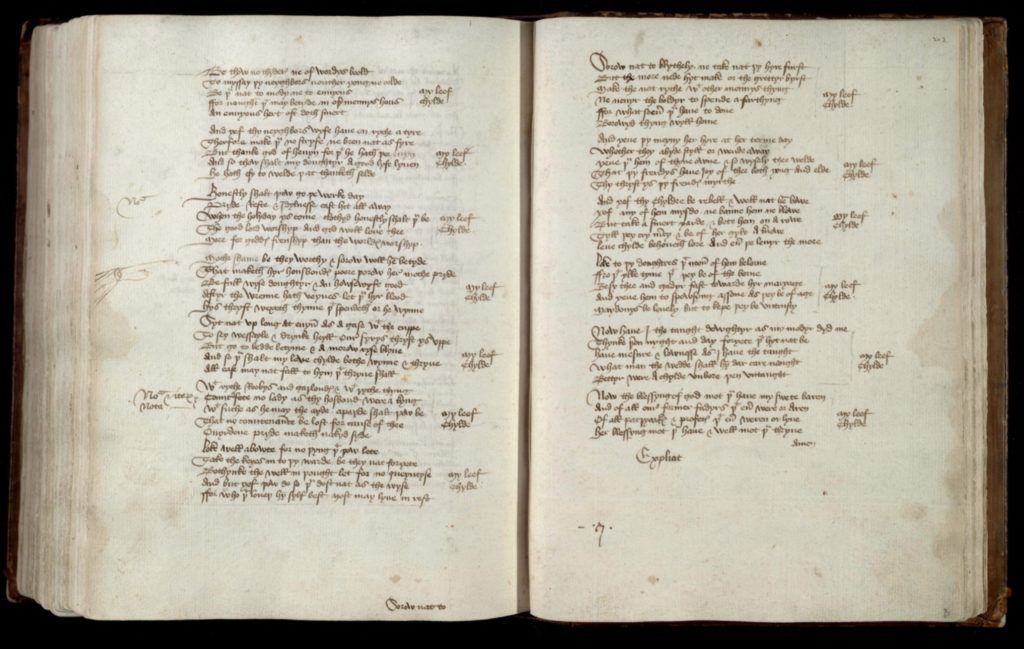

As advised in the fifteenth-century poem, How the good wife taught her daughter, Katherine knew well that ‘meydens thei be lonely / and no thingew syker therby’ and needs must ‘be…agode stowerde [that] wantys seldom any ryches’. But her daughter was yet to learn another lesson of the same poem, ‘Make thee not ryche of other mens thing / the bolder to spend be on ferthyng / Borowyd thing must nedys go home / if that thou wyll to heven gone’.

The circumstances of mother and daughter changed dramatically soon after Margaret’s letter was sent. In December 1512, Katherine’s son, Margaret’s brother, Henry, received the king’s letters patent to take the title and inheritance of his grandfather as earl of Devon. Katherine’s custody of the Courtenay claim was at an end. In 1514 Margaret’s time at court brought her mother’s hope-for result and she was married to Henry Somerset, the eighteen-year old heir to the earldom of Worcester. The marriage lasted about twelve years. The date of Margaret’s death is not recorded but probably it was before her husband inherited his title in 1526. She did not survive to live in the style of a countess like her mother, Katherine.

With thanks to Katie Edwards, Collections Manager, Powderham Castle