Posted by Edward Mills

4 March 2024Research institutions come in all shapes and sizes. As medievalists, we’re used to the rhythm of a good ‘archives trip’: the early start, the queuing to get the readers’ card set up, and (of course) the indescribable thrill when the wonderful team working there make the documents you’ve requested appear before you for the first time. The ‘core’ of the experience is similar wherever one finds oneself, but it’s the differences from library to library — the quirks of the institution, the rules regarding access, and of course, the objects themselves — that guarantee that no two archival visits will ever be the same. This is something that we’ve tried to showcase over the last few years, through a series of ‘Research Postcards’ that have taken us from the Bodleian Library in Oxford to municipal holdings in Darmstadt. Today’s postcard, though, is altogether closer to home for Exonian medievalists, written as it is from our very own Devon Heritage Centre.

The Devon Heritage Centre may not have the scale of holdings of the Bodleian, but in many ways, it’s no less of a gold-mine for the eager medievalist. At the time of writing, it’s only open three days a week (Tuesday — Thursday), and as such can often fill up very quickly. It’s one of the biggest providers in the region for research into family history, and many of my fellow readers during my visits over the summer were working to trace back their own genealogies.

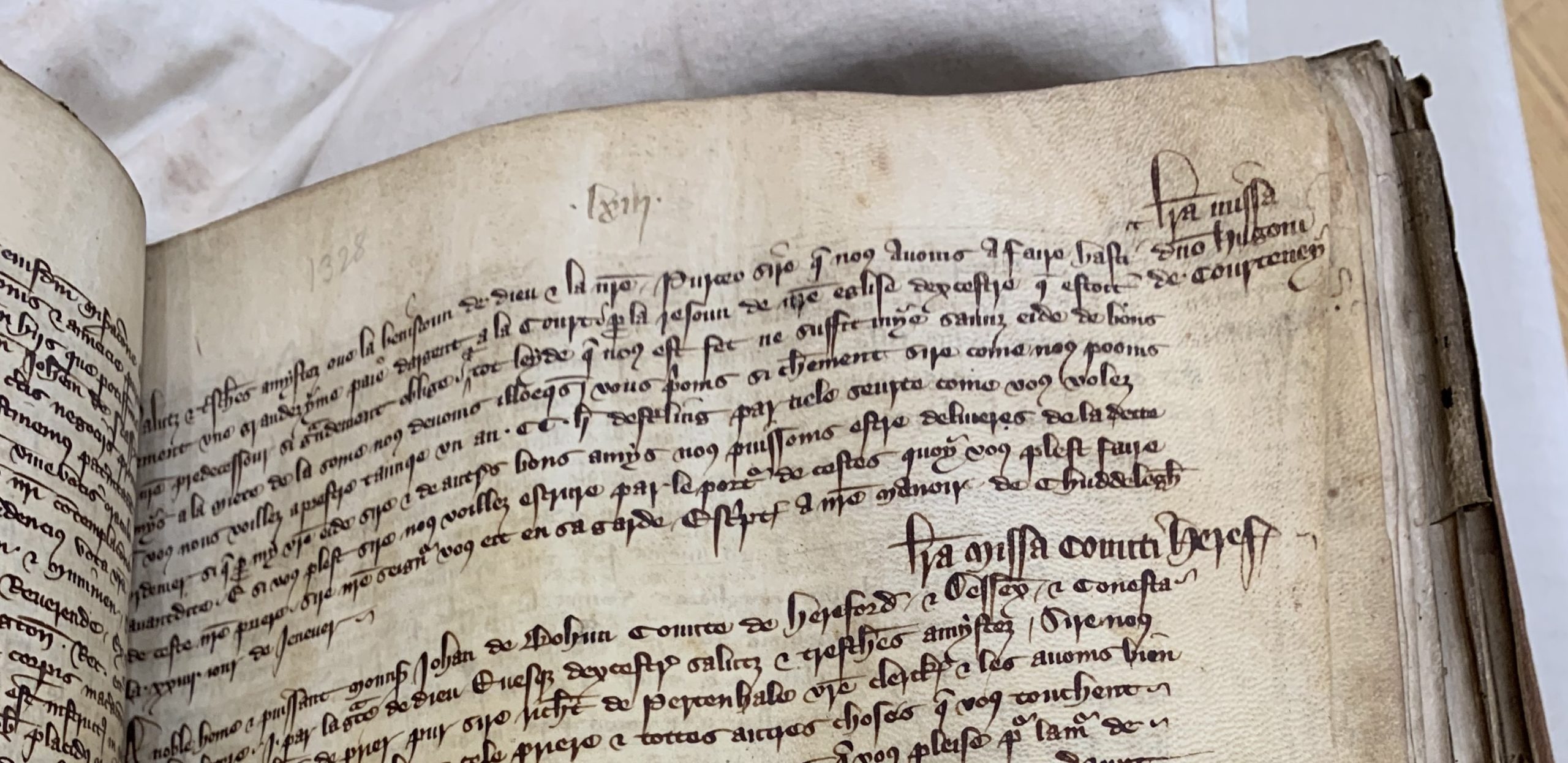

Not being from Devon myself, my visits to the Centre were for an altogether different reason: I was looking at the episcopal registers of John Grandisson, Bishop of Exeter from 1327 to 1369. Grandisson is a monumental figure in the history of medieval Exeter, and as such, has been discussed on numerous occasions on this very blog. My own small contribution to Grandisson studies has been to edit and translate a small portion of Grandisson’s Register; specifically, the exchange of letters that it records between Grandisson and one of the major landed aristocrats of the region, Hugh de Courtenay (Earl of Devon from 1335). The entire contents of the Register were edited over three monumental volumes by F. C. Hingeston-Randolph in the late 19th century, but their precise contents — including those of the missives in French penned between Grandisson and Courtenay between 1329 and 1340 — have been less explored than one might expect, largely on account of Hingeston-Randolph’s conservative editorial practice and lack of a translation. The resulting publication — which has just appeared in the journal Historical Research — makes these letters available to a non-specialist (and particularly non-Francophone) audience for the first time.

Sitting at the long, modern, well-lit tables of the Devon Heritage Centre — itself just off the A30, next to the Park and Ride and past the Subway and Domino’s— it would have been to slip into a very detached, impersonal view of the documents in front of me. Doing so, though, would have been to lose sight of just how personal these letters themselves were, and of the depth of feeling that they hold. After all, to say that Grandisson and Courtenay had a tempestuous relationship would be something of an understatement. The eight letters found between them in the Register (of which six are written from Grandisson to Courtenay, one from Courtenay to Grandisson, and one — intriguingly — from Grandisson to Courtenay’s wife) chart the course of a relationship that soured from early on, as an early request from Grandisson for funds to pay off a debt to Rome is rebuffed. Matters between them remained sour for over a decade afterwards, with Grandisson penning in 1335 an amendement d’alme (a piece for the ‘correction of the soul’) exhorting Courtenay to ‘tolerate in good graces Holy Church and its ministers’. It wasn’t until 1340, with Courtenay’s health failing, that any signs of a rapprochement between the two men emerge, as Grandisson expresses a hope that ‘that all things will come to everlasting good, whatever the case may be with respect to past events.’

The full exchanges between the two powerful men — one a champion of episcopal authority, and the other resentful of clerical over-reach — attest to a lot more than mere antagonism. The modern reader is reminded throughout that, in spite of their differences, the two men also had to work together, whether on the appointment of individuals to ecclesiastical positions or to respond to frustrated vileins in Tiverton. In the letters between Grandisson and Courtenay, we see one of the long-standing debates of medieval Europe — how the Church and the state, loosely defined, should relate to one another — played out on a local level, and it’s worth taking a second to remember that this local tussle is recorded and preserved thanks to the work of local archives. My work in the Devon Heritage Centre has reminded me that, tempting as it may be to make a beeline for the behemoths of the Bodleian and British Libraries, there are treasures to be found far closer to home.

If you’d like to explore the Devon Heritage Centre’s catalogue for yourself, you can take a look here.

Featured image: Devon Heritage Centre, MS DEX/1/a/3, fol. 63r (detail).