Posted by Sarah Hamilton

20 May 2024This year, thanks to funding from Exeter’s Education Incubator fund, 8 final-year students have been co-researching, with Sarah Hamilton and Stuart Pracy (in Archaeology and History) and Ellie Jones and Emma Laws (Exeter Cathedral’s Archivist and Librarian), one of the manuscripts in Exeter Cathedral Library. The aim of the project was to pilot a new, hands-on approach to training in manuscript studies. The students worked together to research and update the catalogue entry for this manuscript. Last week’s post shared their experiences of meeting the manuscript, MS 3513, for the first time; this week, they offer their top tips for reading medieval manuscripts, based on their experiences with the Pontifical of Edmund Lacy (Bishop of Exeter, 1420-1455).

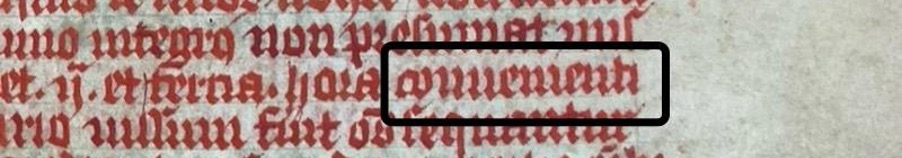

Medieval texts can often be rather intimidating to read. However, breaking it down into smaller units makes it more manageable; the smallest unit is the minim. A minim is the vertical stroke composing letters such as, ‘M’, ‘N’, ‘I’ and ‘U.’ What makes minims so difficult to read is the fact that a long word may have many individual minims making up many different letters.

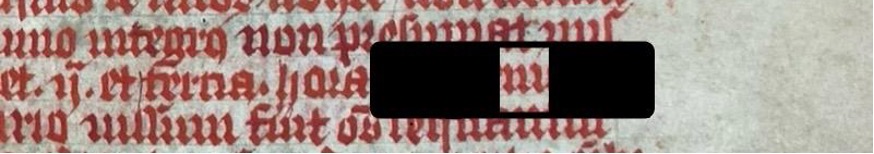

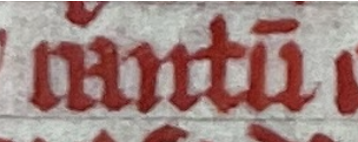

Here we have circled a particular word which has 16 minims! Can you read it? If not, don’t panic – count the minims and split them into letters. Covering the rest of the word aside from the letter you’re focusing on will also help, which we have done here for you.

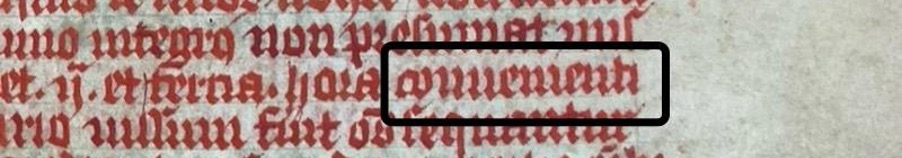

The first four minims are the first three letters, which is ‘con’. The tops of the letters are joined, which makes it a little unclear.

Bearing in mind that Latin does not have a ‘v’, the next letter is a ‘u’ and then an ‘e’. Do you see it?

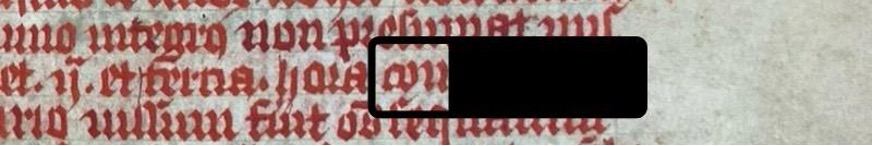

The second part of this word might be easier, as there are fewer minims. The next letters are ‘n’ and ‘i’:

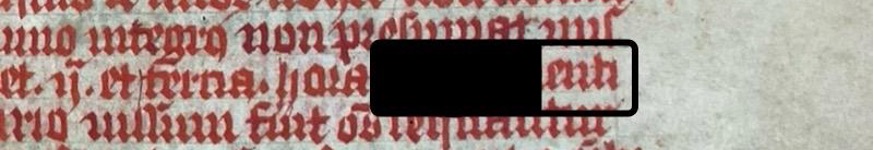

The final four letters are slightly clearer and are ‘enti’:

So the word is conuenienti; this translates from Latin to English as ‘to congregate’. Well done!

While reading an ecclesiastical manuscript it’s handy to recognize your ‘go to’ words, that you will always recognize. This is great news, because they do tend to come up very frequently! Some of these are:

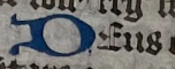

Deus, ‘God’

Amen

et, ‘and’

altaris, ‘altar’

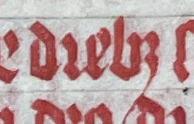

diebus, ‘day’

Marie, ‘(the Virgin) Mary’

digna, ‘worthy’

fiat, ‘let it be done’

ecclesiam, ‘church’.

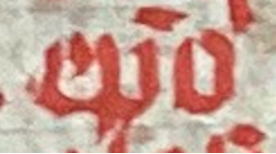

One of the most common abbreviations you will come across is a small line placed above a word, which represents either a single omitted letter …

cantu(m), ‘singing’

… or several missing letters:

ep(iscop)o, ‘bishop’

d(omin)us, ‘(Our) Lord’

You will also find that specific symbols represent a specific collection of omitted letters:

In this example, the long ‘z’ or ‘ȝ’ symbol extending down below the line represents the omitted ‘-us’; being attached to the letter ‘b’ indicates the word reads d-i-e-b-us for diebus, meaning days.

And sometimes single letters can represent a whole word:

a(ntiphona): A chant in the medieval mass known today as the ‘antiphon’

versiculus: another part of a psalm in the medieval mass

The fuzziness of these images points to one of the possible drawbacks of working on digital images of the manuscript: looking at the actual document in person is often much clearer.

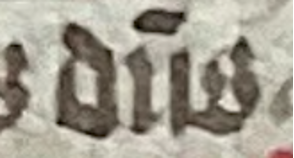

Sometimes two letters share the same minim and this is known as a ‘compression’. Now you know that the line above ‘n’ represents one or more omitted letters, you should be able to read the first part of the following word. The ending is an example of a compression … which two letters do you think these could be?

Sometimes you will come across letters which seem impossible to interpret. But don’t panic! This could be two letters merged together, making them very difficult to separate. When they are joined together like this, it is known as a ligature.

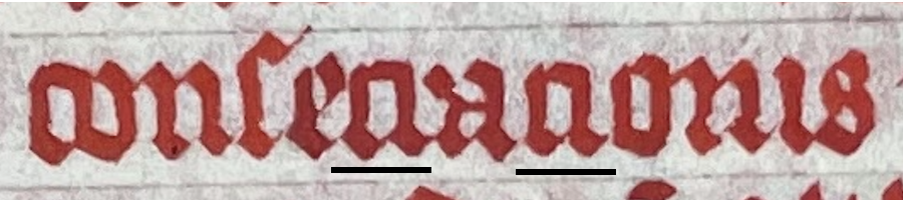

An example of a ligature is in this word consecracionis, meaning ‘consecrations’. You can see the ‘c’ and the ‘i’ (underlined in the picture) have been joined together. Another part of this word to be careful of is the ‘-cra-’ section, also underlined. Beware of the ‘r’ which breaks in half but joins to the following letter ‘a’.

Some letters are not as obvious as others. Let’s start with the letter ‘a’:

This is one example of an ‘a’, looking like our modern ‘a’!

This is also an ‘a’, which looks like our capital ‘A’, but this can be found in the middle of a word as well as the start.

But although it looks like a modern cursive ‘a’, this is an example of a ‘c’.

This is what a ‘c’ looks like at the start of a word. This example is the ‘con-‘ from the word contra.

This is what a ‘c’ can look like in the middle of a word. This word is hicerna!

This is an example of an ‘r’ found in the middle of a word.

This is what an ‘r’ looks like in the middle of a word! This r is found between a ‘t’ and an ‘a’, from the word contra.

This ‘s’ looks to us like a modern ‘S’ and is usually found at the end of words.

However, this is also an ‘s’! This is a tall ‘s’ and is found at the start and middle of words.

This is what the tall ‘s’ would look like at the start of a word; this word is super.

Can you make out some of the example letters in this word? This word is successoribus, showing how ‘s’, ‘c’, ‘r’, and other letters appear together in a word.

So those are our five top tips for reading medieval manuscripts; but the most important thing to remember is not to panic! Next time you’re reading a manuscript, stay calm and remember these steps. There’s no rush: these manuscripts have been around for 600 years – they’re not going anywhere …

Ella Carroll, Laura Dicker, Hannah Fraser, Tom Hitchin, Bethan James, Anna Lochhead, Elle Norrish, and Sofia ali-Shah