Posted by Philip Wallinder

27 May 2024On the 6th of March 2024 a group from the Centre for Medieval Studies made a pilgrimage to Salisbury Cathedral. Our visit began with a tour of the cathedral and chapterhouse in the morning with a visit to the cathedral library in the afternoon. A recurring theme throughout my tale will be my failure to take enough photographs, but then cameras didn’t exist in the middle ages! Many of the photographs below were actually taken by Anne Gwatkin during our trip.

Visiting historic churches is one of my favourite things to do because, unlike most medieval buildings, they continue to be used for their original purpose. Medieval studies can often appear quite dry, lots of Latin charters and account rolls to go through. Even the material culture can feel quite remote from modern life and difficult to relate to. By contrast, medieval churches are still “living buildings” whose modern users have to constantly negotiate and engage with their medieval history. As experts in medieval history and culture we can contribute positively (I hope) to the use and interpretation of these buildings, which is why I think it’s important to visit them.

Our contingent from Exeter arrived at the cathedral just before noon, where we met several other members of the Centre for a tour given by one of the cathedral guides. This covered the history of the cathedral from the original Norman foundation at Old Sarum, to the refoundation in Salisbury in the early 13th Century up to the present. The cathedral was completed in only 38 years between 1220 and 1258, so the whole building was built (almost) entirely in one architectural style, early English Gothic. The exception are the perpendicular arches in the nave which support the spire, added some eighty years later. A fact I did not know before this visit was that Salisbury Cathedral’s spire is only the tallest in England because the taller spires at Lincoln and Old Saint Paul’s in London fell down. The spire at Salisbury owes it’s continued survival to reinforcements added in the 17th Century by Sir Christopher Wren, almost entirely hidden by a lantern ceiling, which you can see below:

One of the things I really love about historic churches are the small details that were added to the fabric by individual artists over the centuries. One example pointed out to us was by our guide was the bishop’s tomb with a monkey on top carved as though he’s throwing nuts at passers by below. Unfortunately, the Cathedral has been subject to several programmes of “improvement” over the centuries which erased many of these unique features, our guide had some particularly choice words for James Wyatt, who was responsible for the removal of the original rood screen and most of the stained glass in the 18th Century. However, churches are ’living’ buildings, constantly being reworked and updated, and sometimes we don’t appreciate the work of past generations. Hopefully, the new font and alters that were installed at the turn of the millennium will be enduring. You can see the alter in the nave in the image below; I neglected to take a photograph of the font, which is large enough to take a grown adult, but you can read all about it from the sculptor, Willian Pye, who also made the alters.

After lunch it was time to head to the library and view some of the manuscripts in the collection. Salisbury Cathedral library is very special because it is still housed in the original late-medieval building, albeit somewhat modified. The library was constructed in the 15th Century over part of the cloister, in subsequent centuries the weight of the building and books began to cause the cloister below to collapse, and the decision was taken to demolish the far end of the library, leaving about half of the building remaining. Our host for this part of the trip was Dr Anne Dutton, the cathedral librarian, whom I first met when researching two manuscripts held in the cathedral library. We got to see a variety of manuscripts from the 10th to the 15th Centuries related to the Cathedral and the work of its canons, you can find a full list of these at the bottom.

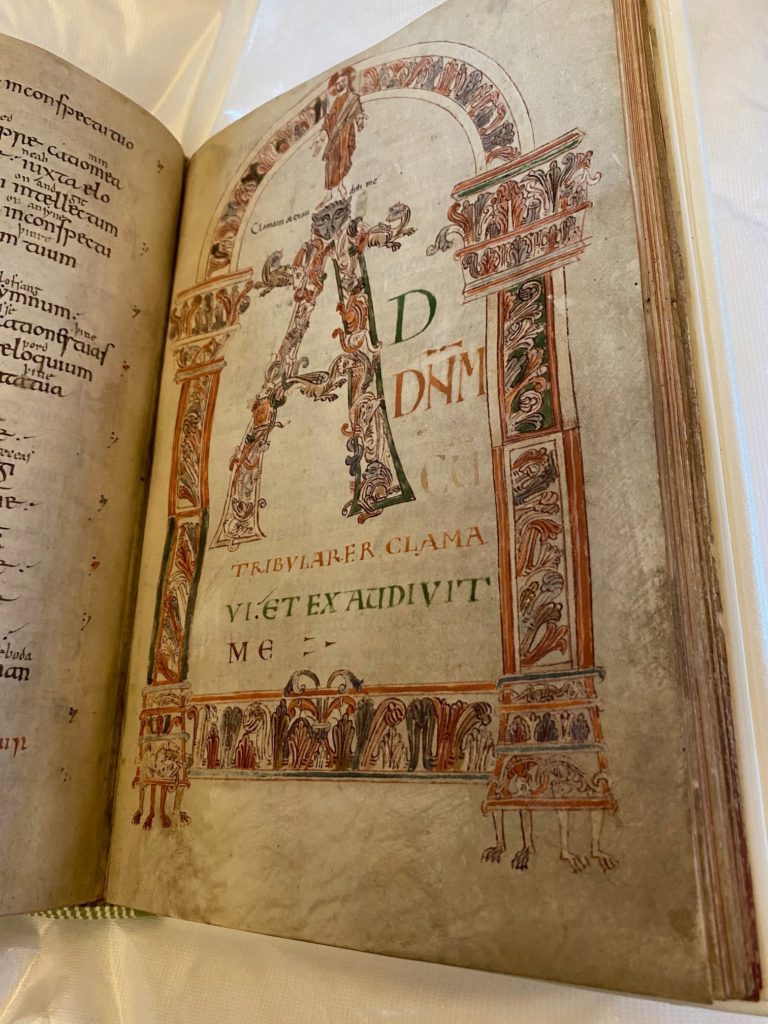

MS 150, known as the “Salisbury Psalter”, dates from the late 10th Century, and is a wonderful example of an Anglo-Saxon manuscript. This is also, I think, the oldest intact manuscript I have personally seen outside a glass case. This manuscript has been sadly injured by having some of the leaves and decorated capitals cut out, a reminder that past generations did not necessarily value manuscripts as texts, but only as “works of art”. The manuscript has an Old English gloss to the psalms was added in the early 11th Century and there were amendments in the 12th and 13th Centuries, demonstrating that the manuscript was actively used both before and after the Norman Conquest:

MS 113 is the first half of a manuscript donated to the Library in the 15th Century by one of its canons, Master Thomas Cyrceter, the latter half is now MS 39. When he donated the books Cyrceter stipulated that they were to be “chained in the new library”, the same building in which they are housed today. The manuscript itself is what we call a “miscellany”, an anthology of shorter texts bound together as much for convenience as because they represent ay sort of coherent collection. This half of the manuscript begins with a copy of Chaucer’s Boece, his translation of Flavius Boethius’s De consolatione philosophiae (On the Consolation of Philosophy).

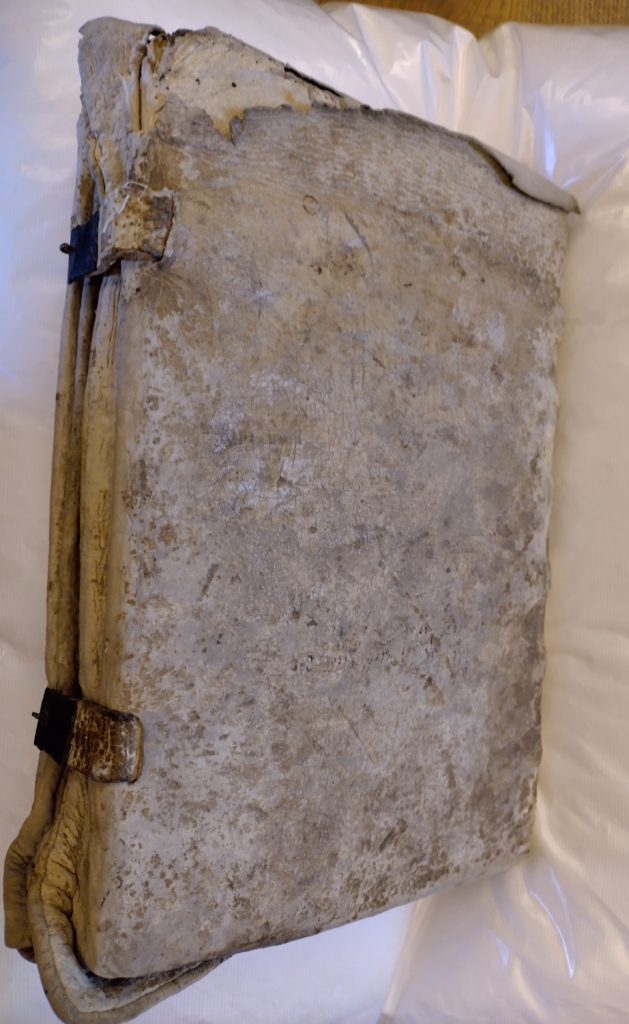

MS 147 is another miscellany from the 15th Century, but this one is noteworthy because of its original “chemise” binding. This is a soft leather cover that wraps around the book which Dr Dutton quite accurately described as a “dust jacket”. However, unlike a modern dust jacket this is an integral part of the book cover.

The full list of manuscripts we saw was:

MS 38 – Aldhelm, early 11th Century.

MS 150 – Psalter, late 10th Century, (“The Salisbury Psalter”),

MS 128 – Augustine, 12th Century.

MS 53 – Minor Prophets, late 12th Century.

MS 121 – Geoffrey of Monmouth, 12th Century.

MS 113 – Chaucer etc., early 15th Century.

MS 147 – de Burgo, early 15th Century.