Posted by Edward Mills

10 June 2024Almost 18 months after large language models first burst onto the scene, the furore surrounding generative AI shows no sign of abating. In this, the final blog post of the academic year, I’m emphatically not looking to take a decisive position in the debate surrounding the place of large language models in teaching, learning, and research (insofar as there are clear ‘sides’ in this ongoing and complex discussion). Instead, and in response to the recent (at the time of writing) release of GPT-4o, I thought I’d try a fun experiment, one that supposedly plays to generative AI’s strengths in generating additional text based on training data.

Journalists have experimented — with mixed results — with asking AI to write a new Shakespeare play and duets between Taylor Swift and Beyoncé. No-one, however, has yet dared to ask the essential question: can ChatGPT write medieval French? Armed with three prompts, and in the wake of a fascinating conversation with my colleague Tom Hinton, I thought I’d try to find out.

Sous l’ombre douce d’un chêne ancien,

Chevaliers vaillants veillent sans fin,

Leurs épées d’argent brillent au clair matin,

Et leurs cœurs ardents ne craignent point le venin.

La belle dame aux yeux d’émeraude,

Sa voix charmeuse comme l’eau qui rôde,

Chante aux étoiles de minuit la ballade,

Des amours perdus et des nobles croisades.

Aux murs épais du château haut perché,

Le vent murmure les secrets oubliés.

Under the sweet shade of an ancient oak

Brave knights watch without end;

Their silver swords shine in the morning light,

And their fervent hearts fear no poison.

The beautiful dame, with emerald eyes

And a voice charming as the flowing waters

Sings a ballad to the midnight stars

Of lost loves and the noble Crusades.

Perched high on the thick castle walls,

The wind whispers forgotten secrets.

Perhaps I shouldn’t be too harsh on ChatGPT here: like the related concept of ‘medieval French literature‘, the phrase ‘medieval French poetry’ is incredibly broad, and doesn’t offer a very specific ‘steer’ for any large language model. Nevertheless, on reading this output back, I do find myself reminded of Neil Gaiman’s memorable comment that generative AI doesn’t produce information, but instead merely offers ‘information-shaped sentences‘. The poem reproduces a set of stock motifs that are straight out of what David Wallace calls the ‘romantic Middle Ages’, as three separate focal points – knights, ladies, and the wind – jostle for the reader’s attention. Insofar as these ideas do reflect anything genuinely ‘medieval’, they are undercut by how they are juxtaposed against one another: if the hero of the Chanson de Roland, with his sword Durendal, is to be found in the first stanza, he’d likely end up with whiplash from how quickly attention moves on to the courtly lady (and, indeed, to a tone much closer to the 14th century than the 11th).

The output is furthest from being ‘medieval’, however, in its language. While the piece is written in grammatically-correct French – albeit a slightly stilted, and extremely formal, one – it is a French that at a glance would be more at home in the 19th century than the 13th or 14th. Clearly, then, some more coaching was needed if I was to get a more authentic-sounding response.

Qui Deus a duné escïence

e de parler bone eloquence,

ne s’en deit taisir ne celer

mes beles rimes deit reveler.

La lune brille sur la mer paisible,

Les chevaliers chevauchent infatigables,

Vers l’aventure et le destin glorieux,

Portant l’honneur de leurs aïeux.

Whoever God has given understanding

And eloquence in speaking

Should not keep quiet about it, or hide away,

But should showcase beautiful rhymes.

The moon shines upon the placid sea

(And) the indefatigable knights ride on

Towards adventure and (their) glorious destiny,

Carrying the honour of their ancestors.

I actually slipped up here, and only fed ChatGPT the first three lines of the prologue to Marie de France’s Lais (in bold) rather than the first four. Nevertheless, the results were instructive. This is a fairly well-known passage, attributed to the 12th-century author Marie de France, and to its credit, the model does manage to create something vaguely akin to Marie’s distinctive dialect of French (known variously as ‘Anglo-Norman’, ‘Anglo-French’, and the ‘French of England’). The fourth line — mes beles rimes deit reveler — keeps the characteristically Norman spelling of deit over the continental French doit, and creates an interesting semantic contrast between reveler (‘to reveal’), and the earlier celer (‘to hide’). The sense of this line isn’t too far from Marie’s, either, as she has ‘Ainz se deit voluntiers mustrer’ (‘But [that person] should willingly showcase it’).

The next stanza, though, is where things fall apart. We’re back to banalities and generalities about knights, in a decidedly non-Anglo-Norman idiom. If ChatGPT was going to create something plausible, it would need a lot more hand-holding.

LI PREECIERES

Oiées, oiées, seigneur et dames,

Que Diex vous soit garant as ames!

De vostre preu ne vous annuit;

Nous volumes parler anuit

De saint Nicolai, le confés,

Qui maint prodige a fait et fait.

Un jour, en mer, un marinier,

Par grand torment fut naufragier.

Cria à Dieu, en désespoir,

Saint Nicolai, prent de nous soing!

Par la vertu du saint sacré

Le marinier fut délivré.

En son église, par humilité,

Rendit merci et charité.

Seigneur et dames, priez ainsi,

Que saint Nicolai vous soit ami.

THE PREACHER

Listen, listen, lords and ladies,

That God might protect your souls!

Do not forget your good fortune.

Tonight we want to speak

Of Saint Nicholas, the confessor,

Who did and does many great thing(s).

One day, a sailor at sea

Was shipwreck[ed] by a great storm.

He cried out to God in desperation,

“Saint Nicholas, take care of us!”

Through the virtue of the holy saint

The sailor was saved.

In his church, (and) with humility,

He gave thanks and alms.

Lords and ladies, pray in this way

So that Saint Nicholas might be your friend.

‘Hand-holding’, indeed. This time, I’d chucked the proverbial kitchen sink of support and prompts at ChatGPT, giving it the title of the work, a date and place of composition (in case it could get a handle on dialectal features), and a reminder — through the phrase ‘authentic medieval French’ — to stick to something resembling the morphology, syntax, lexis, tone and register of the first few lines.

With all that advice, the model did fairly well, suggesting that somewhere within GPT-4o’s training data there may reside a fair amount of medieval French text. There are a few grammatical infelicities, of course: naufragier on line 7 would normally be a past participle (naufragié) rather than an infinitive, but I suspect ChatGPT has prioritised the rhyme with marinier over strict accuracy. On an even pickier note, the following two lines’ rhyme scheme is odder still: while soing is a recognisably ‘medieval’ spelling of modern French soin, it’s more characteristic of so-called Middle French (from c. 1330 onwards) than it is of 1300. Once again, the model performs best when it is able to parrot material from the prompt, with the characteristic spellings of seigneur et dames (as a plural) and saint Nicolai making a reappearance. It even manages to replicate one of the trickiest features of Old and Middle French: namely, its willingness to omit the subject pronoun entirely ([il] rendit merci et charité].

None of this is to say, of course, that the material generated by GPT-4o will revolutionise the field of medieval French studies. One of the most fascinating aspects of the literature of the Middle Ages is its situatedness in time: when studying a period spanning over 1000 years, a text from one century will feel different to a text from another. By comparison, the outputs of large language models fall into an uneasy void, hamstrung by a reliance on the biases towards the ‘romantic Middle Ages’ inherent in public discourse (and hence its dataset). Nevertheless, medievalists might find it thought-provoking to experiment with generative AI in their own subfields. While the Jeu de ChatGPT may not be as authentic or as rich as the Jeu de Saint Nicolas, it certainly has its own things to say about how perceptions of the Middle Ages shape the present.

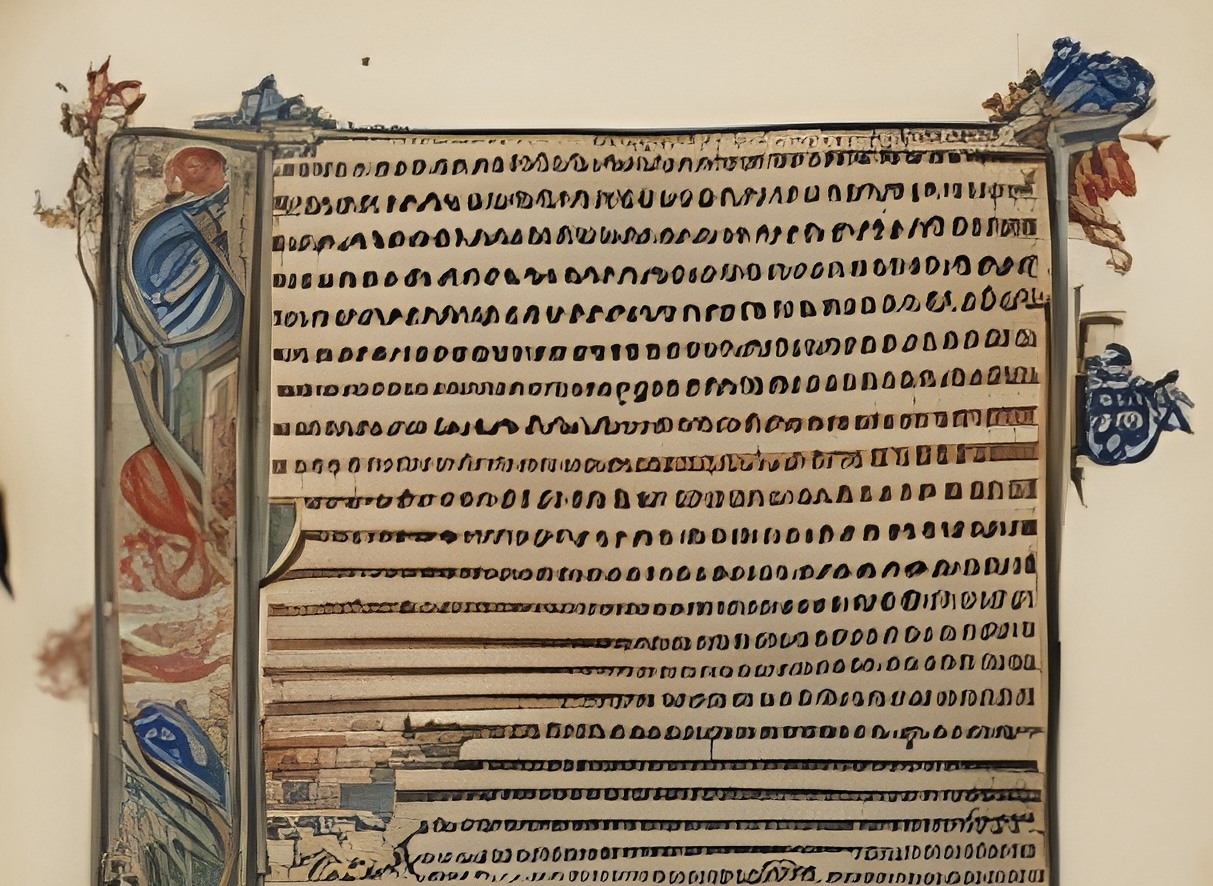

Image: output from deep.ai in response to the prompt ‘A manuscript containing medieval French poetry, with text’ (detail).