Posted by Catherine Rider

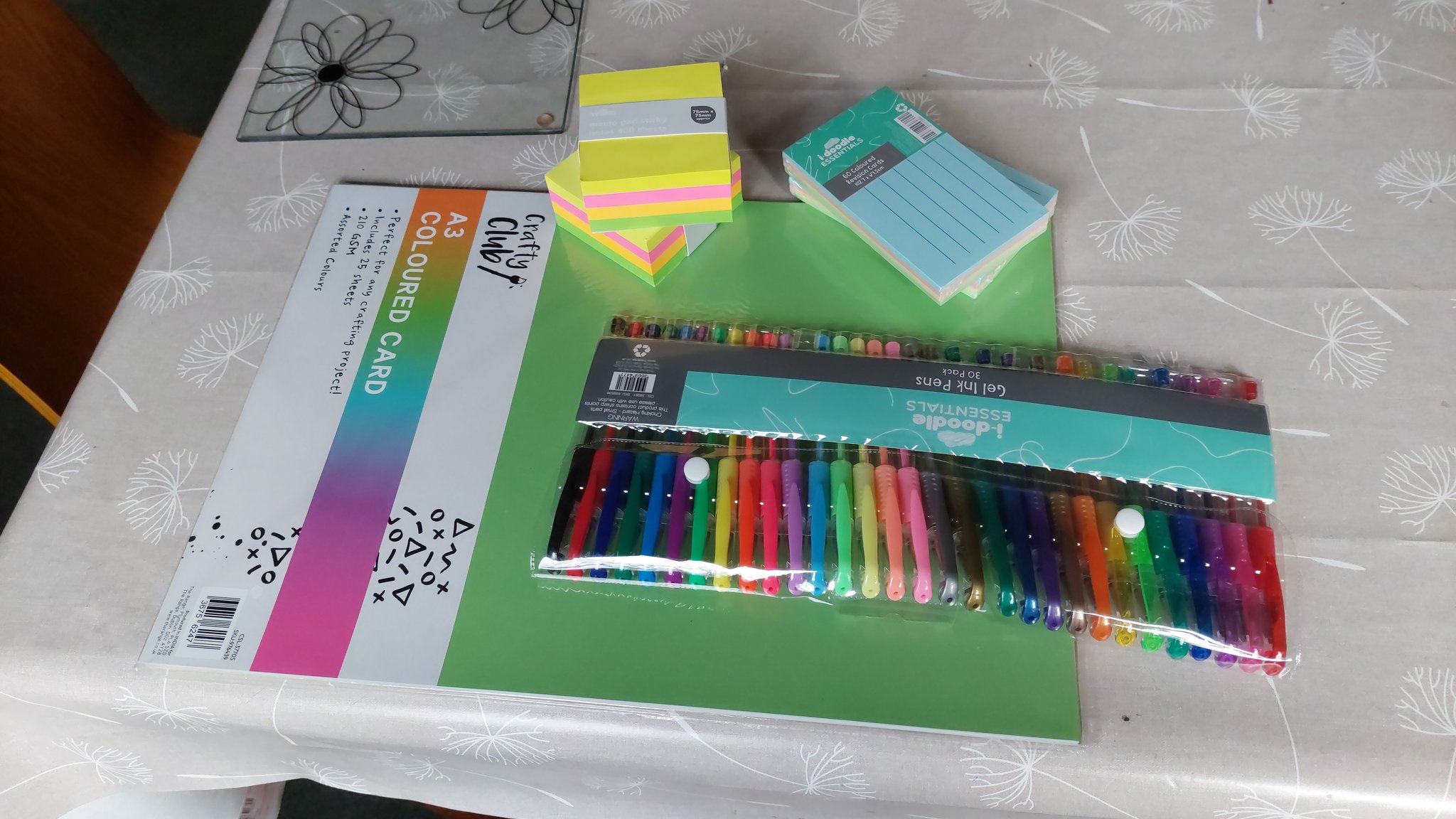

20 January 2025This week’s post is comes from Dr. Catherine Rider, a longstanding member of the Centre (and one of the forces behind the inception of this very blog). Catherine is well-known in the Centre for her public engagement work, but what does this sort of work actually involve (besides purchasing Post-It notes)? She offered to help us find out.

I’ve been doing quite a bit of public engagement work over the last few years and it’s not an area we always discuss much as medievalists. I’m lucky my research areas lend themselves to public engagement work – magic, medicine, fertility and the Inquisition are all instantly recognisable and have popular appeal. In recent years I’ve taken part in events and podcasts, and given talks in settings as varied as the British Academy Summer Showcase, the British Science Festival, the Independent Doctors’ Federation, and the University of the Third Age. I am also shameless about trading on the links to contemporary culture: Harry Potter features quite often in my talk titles. It’s work that I enjoy, and I’ve learned by doing: there wasn’t much advice available when I was a PhD student or early career scholar. With that in mind, I thought I’d write a post that talks about my experience, with some pointers for those starting out.

Essentially it’s talking to people about your research. This can take many forms: giving talks; writing for popular audiences in places like BBC History Magazine or History Today; writing blog posts (like this one!); taking part in podcasts; or having a stall at an event or festival. Bear in mind that in university and REF (Research Excellence Framework) jargon, ‘public engagement’ it’s not the same as ‘impact’: ‘impact’ is about being able to show that a change has happened outside academia as a result of your research, while with public engagement work, that’s not always possible. Public engagement can be a way to publicise your research and make yourself known to partners for future impact-type work, but this sort of development doesn’t necessarily follow from it.

I do it mainly because I enjoy it. I’m always heartened by the amount of public interest in history and in the Middle Ages: you are often pushing at an open door, so to speak. I also find that explaining myself to non-specialists is a great way to clarify my thoughts: what am I doing, why, how? The questions people ask prompt me to reflect on, and think differently about, my research. I’m also conscious that getting paid to research the Middle Ages is a huge privilege; not everyone gets the chance to earn a living this way, so if people are interested in what I do, I feel I have a duty to give something back.

I’ve become more adventurous over the years. I often give talks on something engaging that will be new to the audience, usually with some human interest, context, and pictures. But recently I’ve experimented with more interactive formats, and have learned here from the work done by colleagues in Archaeology. For the British Science Festival, they helped me develop a ‘make your own amulet’ activity. For a recent event at Exeter Library, Sarah Toulalan, Sarah’s PhD student Yishu Wang, and I brought some examples of pregnancy advice from medieval and early modern texts and asked people to write down on Post-It notes any similar advice they’d heard. The idea was to reflect on the similarities and differences in beliefs about pregnancy and childbirth, then and now. Interactive activities like these can work well to get a conversation going. At least, when we managed to persuade the library-goers to stop and talk – we found that if you stand at a table and flag people down, they assume you’re selling something and run away!

What, then, might you want to think about when planning your own public engagement work?