Posted by Nick Holder

10 February 2025We’re thrilled to welcome Nick Holder to the Centre for Medieval Studies blog. In addition to being a Research Fellow at the Centre, Nick is Senior Properties Historian at the charity English Heritage.

I must have one of the best history jobs in town: I’m a ‘properties historian’ at English Heritage and so I visit and write about ruined castles, chapels, monasteries and other miscellanea of the past. There’s a double-random element in what we do: the building or ruin has to have survived into the 21st century to earn its place as ‘heritage’, and, secondly, it has to be managed by the charity English Heritage (if it’s ended up with the National Trust, for example, someone else does the work).

I was particularly pleased to write a new guidebook for Okehampton Castle since it has a longstanding University of Exeter connection. Robert Higham directed a programme of excavation and research at the castle in the 1970s and his prompt and thorough publication of the results (in Proceedings of the Devon Archaeological Society) puts a few archaeologists to shame. He also wrote the first guidebook in 1984 and he continues to carry out research on the site, with his latest article appearing in 2022.

Guidebooks have a long history stretching back to the 18th-century Grand Tour. One of the first was An Account of Some of the Statues, Bas-Reliefs, Drawings, and Pictures in Italy, published in 1722 by the father and son Jonathan and Jonathan Richardson. English gentlemen (and some gentlewomen) bought this and took it with them on their Grand Tour of Italian cultural destinations. In the preface, Richardson senior discusses the purpose of a guidebook: it should go beyond a simple ‘catalogue’ and, instead, be ‘a description well made and carefully attended to, [which] may put a reader almost upon a level with him that sees the thing.’ By the end of the century the compound noun ‘guide-book’ had been coined, for example in Thomas Martyn’s A Tour Through Italy (1791, p. xviii).

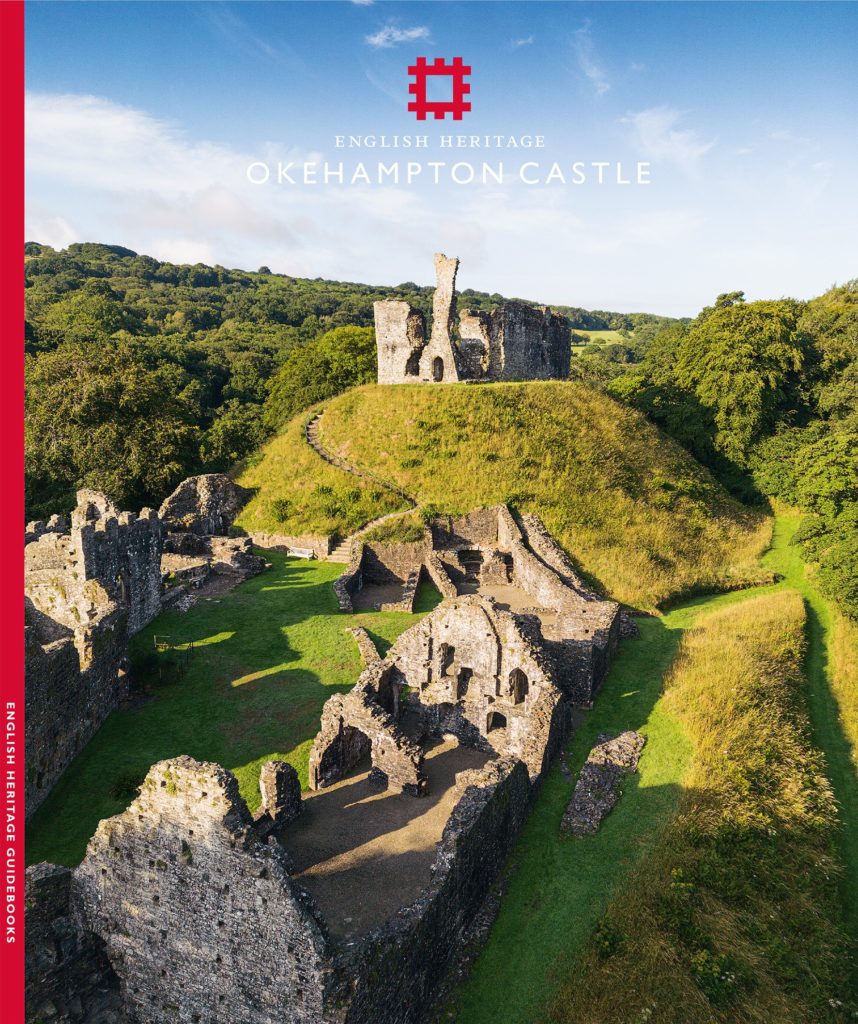

Richardson’s 1722 description of his guidebook gives a sense of their many purposes. Guidebooks can be read by someone planning a visit; they may be consulted by someone unable to go but who wants, as it were, ‘to see the thing’; and they are carried in the hands of a visitor while walking round a site. And, in another echo of the Grand Tour, they help the visitor to remember the place (French souvenir being both a verb and a noun). With the advent of cheap colour printing in the late 20th century the visual aspect of a ‘souvenir guidebook’ has become as important as the textual content.

In 1985 the public heritage organisation Historic Buildings and Monuments Commission (technically a ‘non-departmental public body’) began revising the black and white Ministry of Works guidebooks. For the first time the new versions were colour-printed souvenir guidebooks. A newer format of guidebook, known as the ‘red guides’ series, was launched in 2004, and production continued when English Heritage became an independent charity in 2015. The guidebooks are large enough to have clear colour illustrations but small enough to be held in one hand, and to fit in a handbag or backpack.

We still use the Ministry of Works guidebook tradition of having two sections, ‘Tour’ and ‘History’: with, admittedly, a slight risk of repetition, the first section follows in the visitors’ footsteps, describing and interpreting, while the second section allows the reader to understand the context of, for example, the owner of the castle, or the religious order of the monastery.

At English Heritage the guidebook author works in conjunction with an editor, who naturally takes the reader’s side and must keep the author in check. In the case of Okehampton Castle, I worked with the experienced editor Jennifer Cryer, who defined the word-count of c. 9000 words – designed to fit a 40-page book with c.75 illustrations. Using the existing guidebook by Alan Endacott as a guide, she suggested a plan including word-counts by subheading. I then went off and did the ‘normal’ historian’s work: I read the secondary sources then consulted the primary sources that sounded the most rewarding.

Like any author, I was hoping for a ‘breakthrough’ discovery, perhaps a previously unknown medieval descriptive survey of the castle, or a new Tudor valuation document after its seizure by Henry VIII. But, like many historians, I had to be content with small discoveries and changes of emphasis. Of course, one advantage we have as a historian in the 2020s is time: I had twenty years of other people’s research to draw on since Endacott’s 2003 guidebook, and forty years since Higham’s 1984 guide.

A surprising amount of this new work is by Exeter colleagues. Oliver Creighton has pushed forward the interpretation of Okehampton Castle, considering its landscape and viewpoints. James Clarke and the Digital Humanities team have been working on Powderham Castle manuscripts, including a remarkable 15th-century family tree of the Courtenay family, the owners of Okehampton Castle. And, most recently, Edward Mills has published some rather tense 14th-century correspondence between the builder of Okehampton Castle, Hugh Courtenay II, and John Grandisson, Bishop of Exeter.

After a couple of drafts went back and forth between the editor and me, the 9000-word text was sent to the designer, Derek Westwood, who skilfully laid it out and returned the first design draft. This brought new challenges. I had written, for example, 575 words for the ‘Motte’ and ‘Keep’ parts of the ‘Tour’ section; after the designer had laid this out as a double-page spread, the text was about 40 words too long to fit on that double-page. New aspects that I’d discovered during my research (connections with the Courtenays’ other properties including Tiverton Castle and Colcombe ‘Castle’) just didn’t seem to work in the laid-out guidebook: another painful use of the delete button followed.

As I write this in January 2025, the book has just returned from the printers. It includes newly commissioned reconstruction paintings by Josep Casals. Now, if authors think it’s difficult to work with an editor (and vice versa), try working with a reconstruction artist … I hope to write about this rewarding process in a future blog.

Okehampton Castle is usually open between April and October each year. The Okehampton Castle guidebook costs £4 from the English Heritage website; Oliver Creighton’s excellent guidebook for Launceston Castle is also available.

Header image: Okehampton Castle, by Reading Tom (Flickr.com). Reproduced under a Creative Commons license.

One response to “Writing a guidebook for a medieval castle”

[…] another busy term that saw us writing castle guidebooks, listening to bardcore, and meeting medieval horses (among many other activities), the Centre for […]